Cultural Landscapes of Struggle and Power in the San Francisco Bay Area

East Bay

A People’s Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area aims to challenge some of the widely accepted tropes about the Bay Area’s assumed progressive orientation. Equal parts critical cultural-landscape study, radical historical geography, and richly photographed tour guide, the book asks readers to look more closely at the real, lived spaces of the multi-noded metropolis and see how both everyday and extraordinary struggles over power have produced a simultaneously beloved and deeply uneven region.

People have long looked to the Bay Area as a beacon of liberalism and radicalism in the United States. Place names like “San Francisco,” “Berkeley,” and “Oakland” are often seen as representative of revolutionary spaces where labor, the environment, education, sexuality, race and ethnicity, and countless other social relations are remade by popular movements. But if one is actually there, living and walking the streets, the landscape does not immediately call out, “welcome to utopia!” It is easy to miss the places born of struggle and liberation: sites of resistance to settler-colonialism, enclaves established against white violence, workplaces controlled by their workers, vibrant arts and music spaces, centers of unapologetically queer politics, or even the unassuming corners once occupied by optimistic hackers dreaming of an egalitarian interconnected world.

South Bay

One explanation, of course, has been that recent waves of venture-capital fueled investment has wiped out the visibility of radical histories. There is a kernel of truth there; the explosion of new forms of tech-centered wealth has shaken Bay Area communities in all directions. But there are at least two problems with the story that “San Francisco is over.”

First, there are countless people and communities that are not only hanging on, but fighting like hell to claim their place in the Bay Area. Families that have lived there for generations, decades-old organizations built by groups outside of dominant white-hetero-patriarchal culture, multi-ethnic businesses, fierce-defenders of public spaces. While many such places have faced displacement, many live on as parts of the landscape that are ignored only at the peril of preemptively enabling their erasure.

San Francisco

The second problem with the contemporary declensionist narrative about the Bay Area is that it presumes a prior moment where things were universally better, a sentiment that has, ironically, been rather persistent across time. The inclination to look around and state “This place was better when…” is certainly not unique to the Bay Area, but it reverberates against this place’s progressive history and reifies it into static, romanticized moments.

In many ways, we wrote A People’s Guide to the San Francisco Bay Area against these two narratives, not to deny the brutal erasures wrought by capital, but to offer a set of sites and a set of tools that help reveal obscured histories—and perhaps the chance for different futures—in the Bay Area landscape. For us, each site in the book is a lens to see and think about how the many different ways people have intersected, negotiated, struggled, and travailed to produce this place, and how they persist in it.

The third book in a series edited by Laura Pulido, Wendy Cheng, and Laura Barraclough (including their A People’s Guide to Los Angeles, and A People’s Guide to Boston), our book stretches from the Santa Clara Valley (“Silicon Valley”) in the South Bay, through the East Bay and San Francisco up to Marin and Napa counties in the North Bay. While all of the people’s guide projects share a general orientation to understanding how power manifests in the landscape, each team of authors necessarily has built a guide specific to the places and people at the heart of their region.

The North Bay and Islands

One of our goals was to paint a picture of a more interconnected region than typical “City of San Francisco as center” narratives suggest. In the book, we cover over one hundred sites, situated by essays about each section of the region. Here, we share ten examples that give a sense of the breadth and orientation of the book—stories spanning an expansive geography (and three centuries) of top-down power, bottom-up resistance, and community formation and resilience.

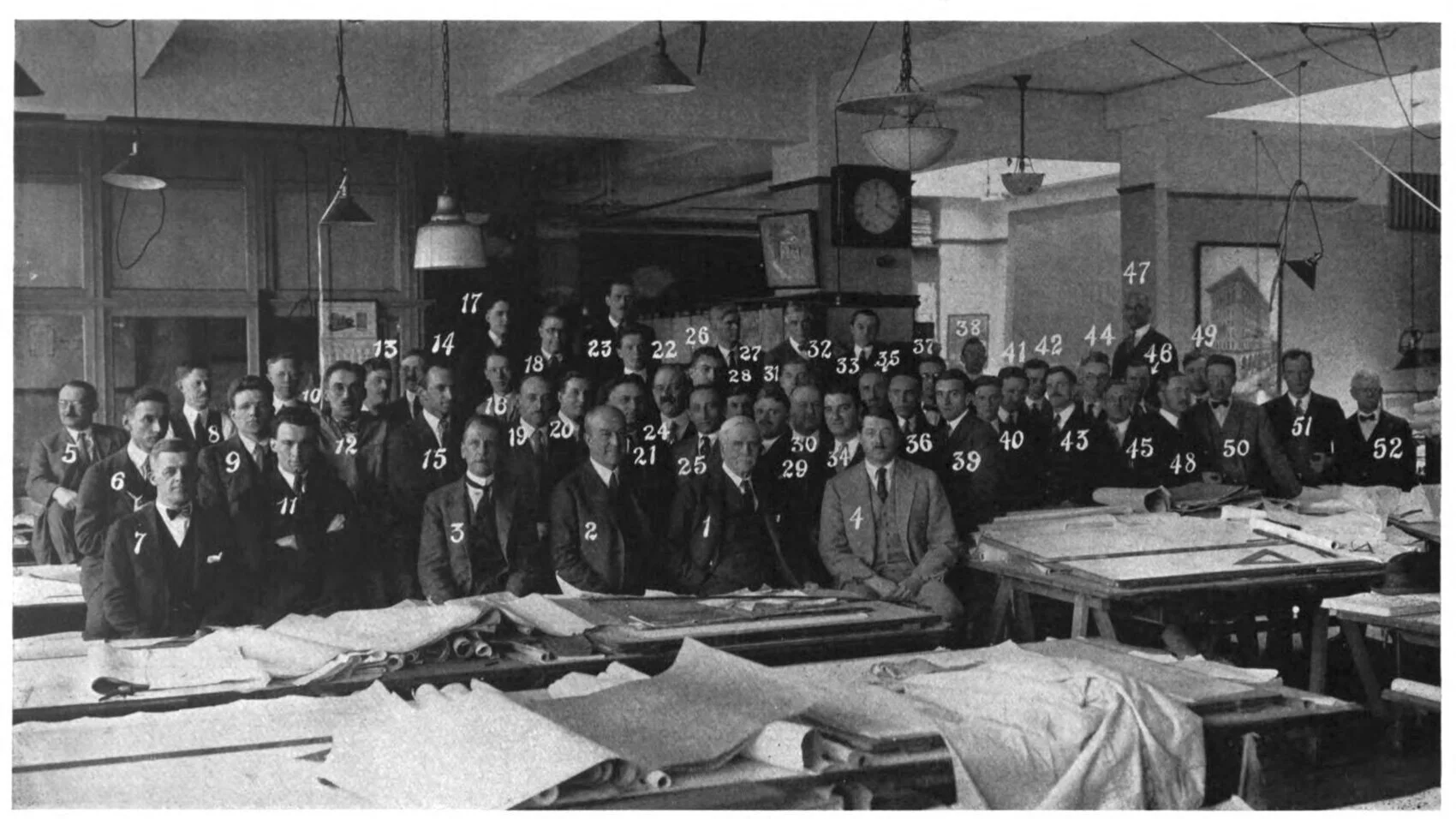

Each photograph is meant to provoke a curiosity about the site, to hint at many different but connected stories. The photographs by Bruce Rinehart appear in the volume itself; the others were taken by co-author Alex Tarr as part of the research process. Together, they illustrate how we looked at the cities around us and asked, “How did it come to be this way? What stories are not immediately visible, but still deeply embedded in this landscape?”

Authors’ note: Other contributors to the book conducted the research for three of the sites featured: Katja Schwaller (Adeline), Will Payne (Piedmont), and Diana Negrin da Silva (Jingletown).