“Radburn Rackets”: Robert D. Kohn and Marjorie Sewell Cautley’s Sketches Against the Speculative Suburb

The Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA) came together in 1923 when a heterodox group of New York–based architects, planners, economists, and other reformers, galled by the footloose patterns of speculative development they saw unfolding on the edges of that city and others, decided the time had come to issue a critique. The next year, the RPAA launched the City Housing Corporation (CHC), which by the end of the 1920s would give physical form to the group’s critique via two projects: Sunnyside Gardens and Radburn. Each was conceived as a “whole” new unit of settlement. Each provided a tangible model of how else to build at or just beyond the edge of town. Neither was uncontroversial.

From the moment the CHC broke ground in the borough of Queens on its novel Sunnyside project, it was common to hear the in-city garden city—now known to many through the vehicle of Jonathan Lethem’s fiction—derided in real-estate circles by skeptics who deemed it socialistic, mechanized, or otherwise regimented, both in its build and in its mores. Among “curbstoners” and “community builders,” card-carrying capitalists and those aspiring to join their ranks, that chorus continued as the CHC jumped to New Jersey, scaled up operations on farmland in the borough of Fair Lawn, and from 1927 etched Radburn onto the map. Even more so than Sunnyside, Radburn challenged the norms of development. It broke decisively with the grid plan and rigorously segregated the trappings of the “motor age” from other modes of circulation. For years going forward, the RPAA found itself embroiled in pitched battles with the tribunes of “normalcy.”[1]

Less often remarked is the extent to which Radburn’s backers relished these battles—and amused themselves in the process.

Nowhere is the pleasure the RPAA took in its quest more evident than in “Radburn Rackets; or, The Adventures of Reddy Radburn” (1929). It is an illustrated booklet printed in a small run—how small, we do not know—by RPAA architect Robert D. Kohn and sent to a few of his compatriots. The occasion for his drawings was the CHC’s fifth anniversary, celebrated March 20, 1929, while Radburn was under construction. The line drawings are simple but striking, distilling interwar debates on metropolitan form with clarity and bite while parroting popular misconceptions about garden-city planning in order to lay bare their absurdity.

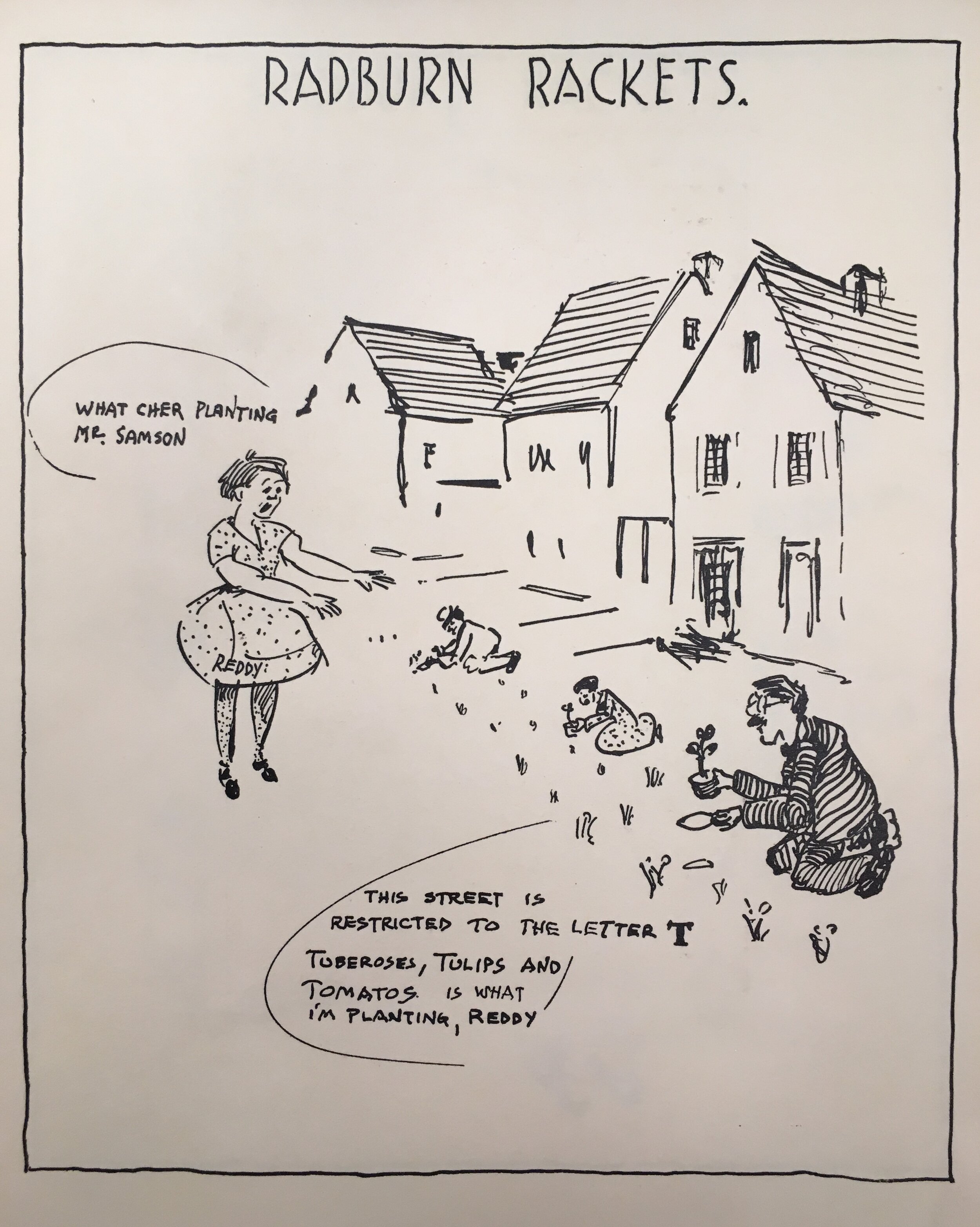

The rhetorical conceit is simple: Kohn is making sport of his critics, mocking them with their own (imagined) words. In several illustrated panels he has “Reddy,” a young girl, ask innocent questions of the builders. They reply in deadpan, caricatures of the skeptics’ fears about approaches to urban development that contravene the profit motive. One (figure 7) reads: “What-cher planting, Mr. Samson?” “This street is restricted to the letter ‘T’. Tuberoses, tulips, and tomatoes is what I’m planting, Reddy.” Another (figure 11): “Are you going to shoot her, Mr. Cop?” “Sure, Reddy. She’s hanging wash on the wrong front.” When Reddy jaywalks (figure 12)—a temptation all but eliminated at Radburn by grade-separated pedestrian walkways—her father is evicted. “To hell with the underpass,” she spouts. The “Very Moving Picture,” as Kohn subtitled the booklet, is introduced with a title page (figure 2), upon which a “poor stiff” is cast as “The House Owner” and the supernumeraries include “engineers[,] architects[,] and managers—lots of ’em.”

Radburn’s detractors, in other words, saw the new town as too coordinated, too ordered, too comprehensive in conception. They imagined Clarence Stein and Henry Wright, its lead planners, puppeteering social life through the medium of the built environment, with countless regulations in place to ensure visual purity at all costs. One panel (figure 10) finds Reddy’s Uncle Milt prowling across his roof to stash an offending bag of garbage in the chimney, hidden away from the inspectors’ gaze. “Who are all those guys finding fault with everything?” Reddy wonders in the preceding panel (figure 9). Resigned, her elder explains, “That’s the advisory bored [sic].”

To the skeptics, the RPAA had assumed a congruence between spatial and social order, landscape and life: in determinist fashion, one would directly and without impediment guarantee the other. The group’s positions were more complex than that, but the subtleties were lost on their willful opponents. To them, Radburn was impossibly utopian, an inhabited scale model, constantly under observation, whose Soviet-manqué stewards stamped out the drift and informality that make city life what it is.

Kohn’s sketches also suggest that the naysayers saw Radburn as a case of architects overreaching as master planners—and getting their way a bit too easily, over and against the harder-headed professionals in their midst. Two panels of “Radburn Rackets” point this up explicitly. “Mr. Engineer” wrecks his car because “those architects put the trees in the wrong place” (figure 6). Even below ground—rather preposterously—there is strife. “Why are you swearing so awfull [sic] Mr. Architect?” Reddy inquires. “Oh those damned engineers insist on putting sewers in my otherwise bee-uuu-tifull streets” (figure 4). There is no indication that this sort of internecine dispute beset the RPAA, but for those accustomed to landscapes with a more laissez-faire look, Radburn’s optics had to be evidence of something more sinister.

Planners, too, came in for rebuke. The agricultural expanse of North Jersey stretches out indefinitely—albeit in a manner far more regular than in actual Bergen County, where Radburn was sited—and “way out there” Kohn sketches a group of “town planners . . . fighting about” land use, physically coming to blows over “whether the crowd at that spot in ten years will support a church or a speakeasy” (figure 5). To plan is to plan ahead. Radburn’s opponents were suspicious of those making designs on the long or even the medium term. Ten years, after all, could be neatly divided into two Five-Year Plans.

Kohn also parries attacks on Radburn’s underlying finances—on Radburn as racket. One panel glimpses the City Vertical (figure 8), where crowds are clamoring to get into (presumably) the CHC office. Alexander M. Bing looks on, his left hand crooked as if pinching a wad of cash. There are not enough houses in Radburn to go around, but investors are welcome. “Those is all overhead!”

Anti-Radburn forces, Kohn indicates, also tarred the development—in this respect no guiltier than other new suburbs—for replacing productive farmland. In Kohn’s first panel (figure 3), Reddy is led to a monument proclaiming “Sic transit gloria spinach,” a play on Sic transit gloria mundi—thus passes worldly glory. “This,” a man tells her, “is what Radburn has done for you.”

As historian Edward K. Spann has shown, Kohn was a key element in the RPAA–CHC milieu. He is less mythologized, or remembered, than Stein, Lewis Mumford, or Catherine Bauer, but was a prime mover in articulating what the buildings at Sunnyside and Radburn would look like, how they would be arranged, and—coupled with Bing’s financing schemes that kept Sunnyside open to the working classes “at moderate prices”—how the assemblage might cut against prevailing patterns of for-profit development. Kohn was a collaborator of Stein’s across the New York metropolitan region, had worked in designing the Emergency Fleet Corporation’s shipbuilder subdivisions during the First World War, served as the American Institute of Architects’ president from 1930 to 1932, and headed the Public Works Administration’s Housing Division after that.

“Radburn Rackets” is the sort of ephemera often lost to history. Fortunately, it survives in the archives of some of its recipients, including Stein and housing reformer Edith Elmer Wood. The copy presented here is from the collection of Marjorie Sewell Cautley, the RPAA’s major landscape architect, whose plantings were integral to Sunnyside and Radburn, and who in 2015 had a segment of 45th Street in Queens named in her honor, a complement to the longstanding Lewis Mumford Way. In the 1920s Cautley practiced out of Paterson, New Jersey, and lived in Glen Rock and Ridgewood, just to the north. While it isn’t clear how many copies of “Radburn Rackets” Kohn sent out, we do know, thanks to Cautley, that he enjoyed creating these whimsical illustrations. Her collection contains numerous cartoons that Kohn sent her over the years, channeling the same visual vocabulary to mark occasions large and small.

There’s no record of Kohn’s colleagues reacting to his humor. We do not know precisely how Cautley read this document. But we find echoes of it in her writings, especially those issued as economic depression (and her own, amply documented in her papers) set in. During these years, Cautley began to rely ever more on visual culture in advancing her views. Two years after receiving “Radburn Rackets,” she published a children’s book, Building a House in Sweden (1931), with her sister, the illustrator Helen Sewell, that yoked simple language to spare renderings of a family’s quest for adequate dwellings just beyond the edge of town—Stockholm—“where people could live who were not very rich.” Kohn’s winking humor has been pared down, but the two works deploy kindred visual strategies as they take on headless housing markets and propose alternatives.

Kohn’s sketches against speculation invite us to dwell on visual genres of critique, however informal, and the channels along which they travel. They also open questions about the role of satire in the service of dissent.

Elsewhere Kohn spoke and wrote forcefully against the frenzy of 1920s development, describing it as “a decade of racketeering and perfect irresponsibility of a certain type of investment banker and speculative builder,” and against the half-measures put forth by President Herbert Hoover’s housing conferences in the early 1930s as “rugged individualism” given the appearance of genuine planning.

In “Radburn Rackets,” Kohn prefers not to. His swerve away from head-on polemic supplies a different, more textured sense of the RPAA’s intellectual repertoire and internal dynamics. There is no accounting for Kohn’s puns, though. Reddy Radburn is joined by a male counterpart named Sonny Side, who laments that he is no longer the center of attention (figure 13). The group’s positions are too easily assimilated to the maximalist, crusading style on display in the work of Mumford, the in-house philosopher, who could be self-serious and dour. Alfred Kazin would later write that Mumford “addressed himself on a large scale to every social problem with the confidence of a Victorian prophet.” Kohn, instead, makes the case for planning by lampooning the anti-planners, letting their own rhetorical excess collapse under its own weight. Kohn preempts them; he negates their negation.

“Radburn Rackets” may not have been central to the RPAA’s formation, but it is productively peripheral, as if on a parallel track to the group’s more formalized visual culture of plans, elevations, surveys, and graphics. Its timing, too, is instructive. March 1929, of course, came just seven months before the crash. Kohn’s one-off adds dimensions to how we might gloss the intellectual prehistory of the New Deal—and offers rhetorical alternatives for those today who would mine its legacy in the face of other crises.

NOTE

[1] The literature intersecting the RPAA, and Radburn specifically, fills shelves at this point. Three able discussions of the “Radburn idea” and its adaptation over time are Eugenie L. Birch, “Radburn and the American Planning Movement,” Journal of the American Planning Association 46, no. 4 (1980): 424–431; Daniel Schaffer, Garden Cities for America: The Radburn Experience (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982); and Kristin Larsen, “Research in Progress: The Radburn Idea as an Emergent Concept: Henry Wright’s Regional City,” Planning Perspectives 23 (2008): 381–395.