“This is the hour”: When Architects Protest

This article is the first in a two-part series.

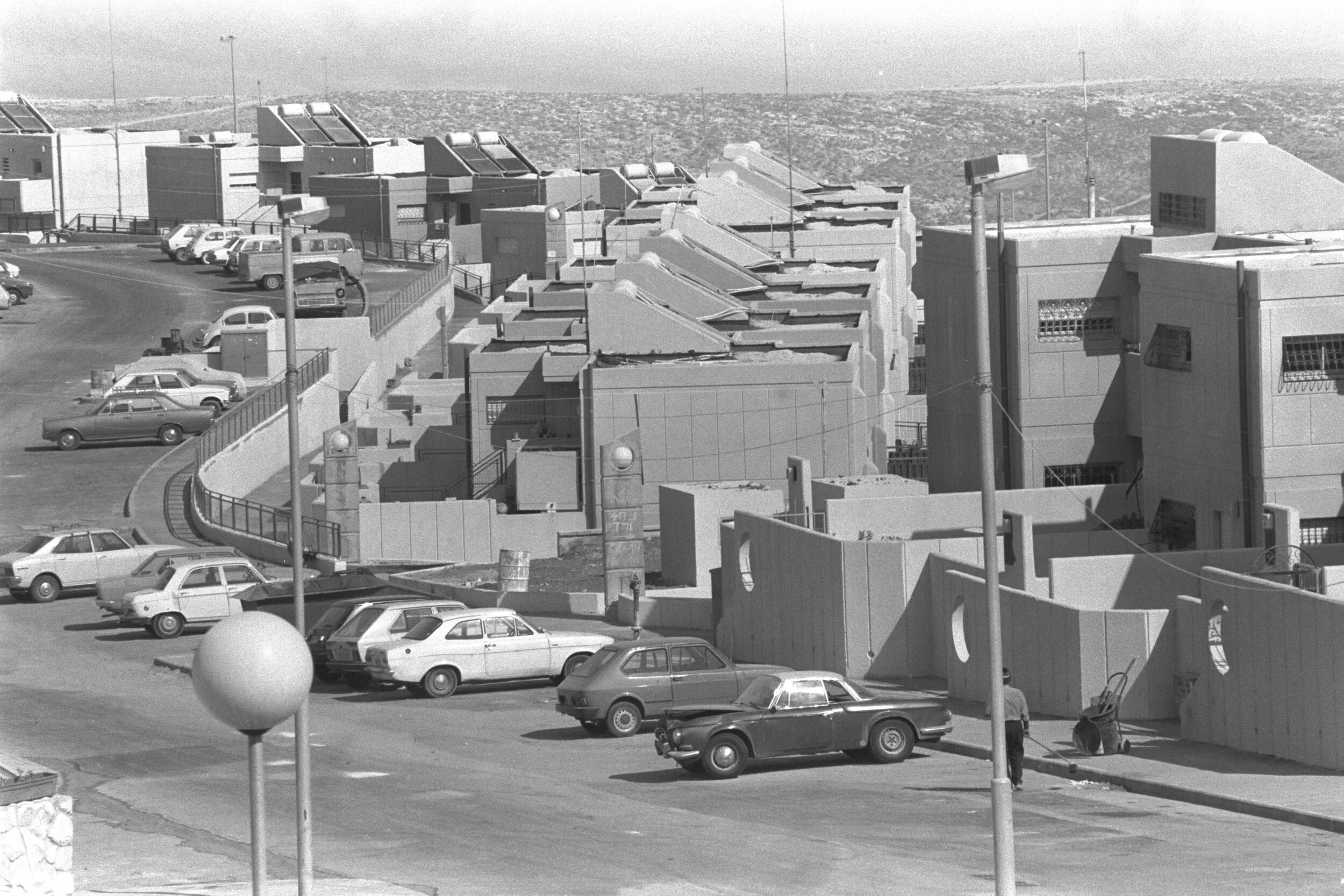

In the winter of 1988, the architects Aaron Weingrod and Judith Green found themselves faced with a dilemma. Born in the United States, both had immigrated in the 1970s to Israel, where they worked at the office of landscape architect Shlomo Aronson in Jerusalem. The office had recently taken a design commission in Ma’ale Adumim, one of the most populous Jewish settlements in the West Bank, a large territory which Israel had captured from Jordan some twenty years earlier (Figure 1). Weingrod and Green felt uncomfortable working on the project because, as leftists, they opposed Israel’s occupation of the territory, which was then home to about a million Palestinians. The outbreak a few months earlier of a Palestinian uprising, known as the First Intifada, reinforced their views about the political perils of the occupation: it made it clear to many in Israel that the Palestinians constituted a national collective that aspired to self-rule, and the construction of any settlement would only provoke conflict.

Figure 1. Residential quarter in the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim, 1983. Photograph by Harnik Nati, courtesy of National Photos Collection, Government Press Office.

When Weingrod and Green expressed their concerns to Aronson, he was sympathetic. But Aronson didn’t think the firm could afford to give up the design commission. Out of respect for Weingrod and Green’s commitments, however, he decided that anyone who opposed the project could choose not to work on it, without jeopardizing their tenure at the firm.

Weingrod and Green were not entirely satisfied. It was clear to them that they were not the only designers in Israel who were faced with such a problem. Across the country, there were many architects who opposed the occupation, but few had openly refused to work in settlements. Weingrod and Green contacted their friend Karen Wainer, a graduate of London’s Architectural Association and a professor at Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem. Wainer was born in South Africa, and so Weingrod and Green had formed a friendship with her also on the basis of their common Anglophone background. Together, they agreed that something must be done. They decided to draft a petition, calling on design professionals to decline commissions and boycott construction in the occupied territories.

Drafting the petition was not as simple as the three architects may have wished. They quickly realized that they would have to exclude East Jerusalem from the boycott zone. Israel had conquered the eastern part of the city, together with the West Bank, in the Six-Day War of 1967. But unlike the remaining parts of the West Bank, East Jerusalem was unilaterally annexed to Israel, and in the years since the area had experienced an unprecedented construction boom, providing much-needed work for architects. Weingrod, Green, and Wainer knew that few would sign a petition prohibiting them from it.[1]

After they agreed on the final version, Weingrod, Green, and Wainer circulated the petition among their peers. It read:

Building reflects cultural and social aspirations. The designer and implementer in delineating modes of life, often entire populations, must be aware of this fact and assume personal responsibility for the consequences of his work. The settling of the occupied territories, excluding East Jerusalem, which constitutes an exceptional case, is a clear manifestation of the occupation and its institutionalization. The one who builds in the occupied territories—town planner, engineer, designer and architect—is a collaborator of the first degree with this trend. This is the hour to take a personal stand. Boycott building in the occupied territories.[2]

“The petition. . . . articulate[d] a new relationship between the design professions, civil society, and the state.”

Within a few weeks, Weingrod, Green, and Wainer had collected 103 signatures. Among the signees were David Resnik, former head of the Israeli Association of Architects and Town Planners, as well as luminaries such as Ron Arad and Eldar Sharon. Very few architects refused to sign the petition, and those who did refused because they saw the act as pointless. Leading architect Dan Eytan insisted that he didn’t believe in petitions. “Petitions don’t do anything,” he told Wainer. Another architect who declined explained that whoever pays taxes, taxes that support the Israeli government, is not in a position to sign such a petition. But these oppositional voices were marginal. As Wainer later recalled, in all, only five or six architects sent the petition refused to sign it.[3]

On August 12, 1988, the petition appeared in local newspapers (Figure 2).[4] According to Wainer, the first few days following the publication were euphoric. The three got many phone calls from friends, congratulating them and expressing their support. Like them, in the wake of the First Intifada, many progressive Israelis had come to oppose the occupation. (According to one source, there were at least thirty protest groups in Israel condemning the government’s policies in the occupied territories in February 1988.[5]) A reporter for the newspaper Kol Ha’ir even wrote a short piece discussing the petition’s popularity among architects who often worked for the state and were “very much dependent on the Ministry of Housing and its projects.”[6]

Figure 2. Copy of the petition, entitled “Against Construction in the Territories,” in Kol Ha’ir newspaper, August 12, 1988, 59.

But the petition didn’t do much. Over the next thirty years, Israel oversaw the construction of hundreds of thousands of homes in more than two hundred settlements. Today, some 450,000 Jewish Israelis reside in settlements (not including East Jerusalem), constituting 14 percent of the total population of the West Bank.[7] All of them reside outside the legal borders of Israel.

When I met Wainer in 2017, she agreed that the petition had failed to arrest the construction of settlements. The mechanisms of the Israeli occupation are just too strong, she lamented. There are too many actors involved in the construction of settlements, and architects who refused to work in settlements were replaced by other design professionals, by engineers, or by the settlers themselves who assumed the roles of architects, builders, and urban planners. “It wouldn’t matter if I refuse to plan a villa or an individual building” in the West Bank, she explained. And, in any case, the architects who signed the petition didn’t develop an institutional framework that could have enlisted more signees or encouraged subsequent protest activities. It was a one-time activity.

Perhaps petitions, as a form of protest, are not the best tactic, Wainer wondered. They don’t require much commitment. Maybe a more on-the-ground resistance activity, like that of the women of Machsom Watch who monitor soldiers’ activities in military checkpoints, she told me, had more chances of making a change.

Was it all for nothing then? Was the petition a waste of time? I asked Wainer. At this point, Wainer, who still today regularly attends protests against the occupation, changed her tone. “Oh, no,” she bluntly asserted. The petition did two important things, she clarified. First, it joined other protest groups that mushroomed during the First Intifada and communicated a clear message of opposition to Israeli settlers. “I wanted the settlers to know that I would never plan a house for them. They are muktzeh [outcasts in Jewish law].” Second, the petition created a rare dialogue between designers and the state. Suddenly, architects took a stand against their government. Until that time, such an act of dissent was rare, perhaps even unheard-of, in Israel. “It was basically a revision of the profession. It said that architecture is not just a service industry. We are not just providing a service. It gave a status to the profession that is usually not given to it.”[8]

The petition, it seems, didn’t have a real chance at stopping the construction of settlements. But what it did do was articulate a new relationship between the design professions, civil society, and the state. As the petition appeared in newspapers and otherwise began to circulate in the public sphere, where it joined myriad other dissenting voices, it helped to create a moral atmosphere in which some practices were acceptable and others were not. Although that atmosphere has since been undermined, and the moral lines blurred, for a while it had a strong effect on the discourse around the occupation in Israel. And that achievement should not be diminished.

Notes

[1] Karen Wainer, interview with the author, August 3, 2017; Shmuel Groag, Hillel Shocken, Karen Wainer, and Aaron Weingrod, “Ethics in Architecture,” panel discussion, Bezalel Academy for Arts and Design, Jerusalem, June 22, 2017.

[2] “Metahnenim Neged Bniya Bashtahim,” May 1988, Karen Wainer’s private collection. The petition also referred to the Gaza Strip from which Israel withdrew in 2005. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are my own.

[3] Wainer, interview.

[4] See, for example, “Neged Bniya Bashtahim,” Kol Ha’ir, August 12, 1988, 59.

[5] See Reuven Kaminer, The Politics of Protest: The Israeli Peace Movement and the Palestinian Intifada (Brighton, U.K.: Sussex Academic Press, 1996), 47–48.

[6] Shahar Ilan, “Adrihalim Neged Bniya Bashtahim,” Kol Ha’ir, July 29, 1988, 1.

[7] According to Peace Now there are 266 settlements in the West Bank. 134 of them were not authorized by the state. See “Settlement Watch: Population,” Peace Now, accessed January 29, 2021.

[8] Wainer, interview.