Architecture and the Eighth Amendment: On Cruelty, Comfort, and Legal Personhood

Conditions of confinement and prisoner’s constitutional rights

The outrage expressed by Linda Logan in her interview on Shreveport’s nightly news was palpable. "You're on death row, you're not supposed to be comfortable. . . . He's been complaining the whole time that he's been on death row, now his sensitive butt is too hot?" Nathaniel Code had been held on death row at Louisiana State Penitentiary since it opened in 2006, convicted of murdering Logan’s sister. Code was one of three inmates who had sued the Louisiana Department of Corrections, claiming that summer heat produced dangerous living conditions in the prison. Their argument: these conditions violated their Eighth Amendment rights.

In simple terms, the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution is a declared limit on government’s power to punish. There doesn’t appear much, at first, to it. The texts reads in full: “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” In this context, the phrase cruel and unusual refers to punishments deemed unacceptable regardless of circumstances (for example, drawing and quartering) or to punishment levied disproportionally to the crime being punished (for example, the death sentence for a minor theft). There is little dispute regarding the applicability of the amendment to these extreme examples.

In the United States today, the prison sentence is broadly accepted as a proper form of state-administered punishment: a legal sanction under current constitutional norms. However, imprisonment continues to trigger Eighth Amendment claims. Many cases invoking the Eighth are so-called “conditions of confinement” claims, having to do with the ways in which prisoners are treated while incarcerated.

The expansion and subsequent contraction of prisoner’s rights in the latter half of the twentieth century as protected by the Eighth Amendment tracks closely with a changing understanding of what the prison, as an institution, is obligated to provide for its inmates. And while prisoner’s rights discourse often heavily implicates prison buildings themselves, the reliance on prison architecture to make evidentiary claims about cruelty and punishment does not happen in a straightforward way. As U.S. Supreme Court Justice Warren E. Burger put it in Gregg v Georgia in 1976, “of all our fundamental guarantees, the ban on ‘cruel and unusual punishments’ is one of the most difficult to translate into judicially manageable terms.”

I would argue that the judicially manageable “translation” of the phrase cruel and unusual requires a spatialized understanding of the prison building — an understanding of that sanction’s necessary physical form that is often obscured in prisoner’s rights discourses.

“Like death or banishment, the prison incapacitates convicts by physically removing them from society.”

The prisoner as “whole person”: Laaman v. Helgemoe

The expansion of rights as protected under the Eighth Amendment reached an apex in the case Laaman v. Helgemoe in 1977, which set a new standard for its broadest application. Brought by twelve inmates held at the New Hampshire State Prison on behalf of all its prisoners, the suit constituted a general complaint about living conditions.

The court’s decision began with an extensive description of the prison buildings, details of which were gathered by the court. The report confirmed the prisoners’ initial complaints: the prison’s overcrowding, which resulted in dirty living quarters and unsanitary food preparation; uncomfortable visiting rooms without privacy; lack of adequate medical facilities; insufficient space for vocational training.

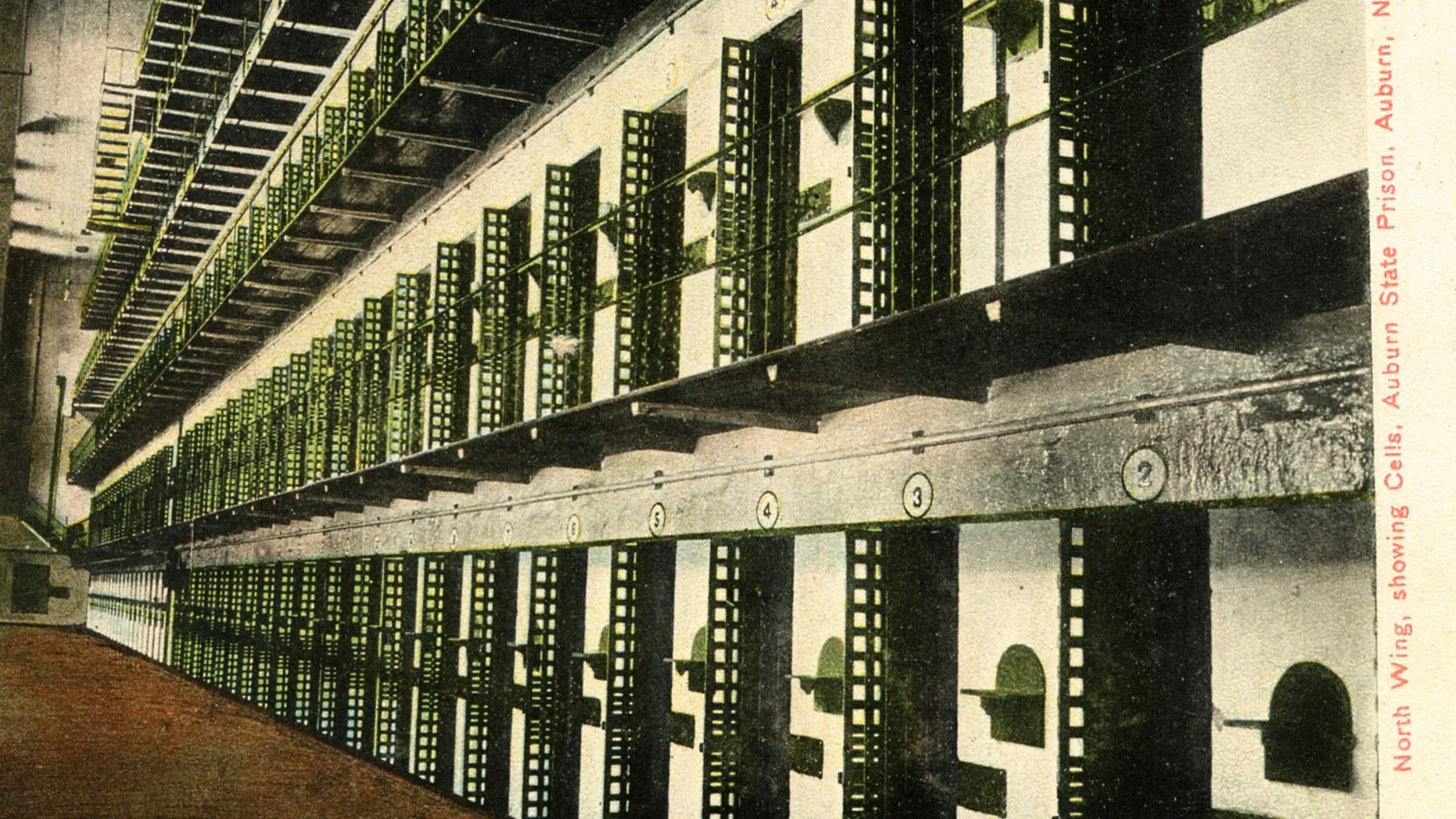

Figure 1. Auburn State Prison postcard. N.D.

The court’s fact-finding missions produced a picture of general institutional neglect rather than acute abuse; a neglect manifested in self-evident inadequacies of the prison building. Built in 1878 following the Auburn Prison paradigm, the structure exemplified that era’s so-called “silent model” of punishment, in which individual cells arrayed along stacked tiers of open catwalks allowed for the surveilled solitude believed necessary to reform the criminal character (Fig 1). Once at the forefront of American penal ideology, the fitness of this design was now in question. The state district court, in granting relief for the prisoners, found that the facilities did not meet twentieth-century standards — to the point that it constituted a violation of its inmates’ constitutional rights.

The ruling was particularly notable for how the court used the building’s physical conditions to frame a surprisingly expansive understanding of rights (Fig 2). “The New Hampshire prison is not marked by barbaric and shocking physical conditions, and there is no flagrantly abusive conduct” wrote Judge Hugh Bownes in his majority opinion. However, he continued, “the Eighth Amendment is not limited to tempering only the infliction of cruel and unusual punishment on the physical body; its protections extend to the whole person as a human being.”

Figure 2. New Hampshire State Prison, Concord, N.H. Interior view showing inmate housing tiers. Stereograph Howard A Kimball, c. 1900. Courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society.

The court’s decision was a forceful acknowledgement of what the scholar Sharon Dolovich has called the state’s “carceral burden.” Like death or banishment, the prison incapacitates convicts by physically removing them from society. But unlike these alternative punishments — where the state’s involvement ends at the moment of the executioner’s stroke — incarceration requires government involvement throughout the inmate’s sentence. Any government that accepts imprisonment as a normalized legal sanction, Dolovich argues, assumes an affirmative obligation to care for incarcerated people while they are housed in prison, since they have been deprived of the ability to care for themselves.

In the Laaman decision, Bownes acknowledged that incarceration necessarily strips prisoners of certain rights and privileges ordinarily afforded to people. However, this did not mean that prisoners could be deprived of basic constitutional protections, including protection against cruel and unusual punishments. In this court’s interpretation of Eighth Amendment protections, the state was required to provide proper living facilities for its inmates.

The decision centered on a detailed survey of the space of imprisonment, acknowledging the building’s physical conditions as a necessary factor in an inmate’s experience of punishment. The court thus implicitly considered the architecture and maintenance of the prison as foundational to the state’s obligation. Importantly, the protections confirmed in this ruling extended beyond the prisoner’s physical well-being. As Bownes put it, “the Constitution demands more than cold storage of human beings who have transgressed the criminal laws.”

It is notable — especially in light of subsequent court decisions — that seemingly banal physical descriptions of a poorly-run prison would form the basis for a successful Eighth Amendment claim. And indeed, Laaman’s expansive view of protections afforded by the Eighth Amendment have been gradually walked back by court decisions which leverage facts of the prison building in service of very different arguments regarding what prisoners deserve.

“Of course, the fiction of objectivity has always been part of law making. In Eighth Amendment law, this fiction placed ever greater burden on the plaintiffs to demonstrate harm.”

Narrowing definitions of prisoners’ rights (Rhodes and Wilson)

Less than four years after the New Hampshire case confirmed that Eighth Amendment protections extended to the prisoner “as a whole person,” inmates brought a suit against the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility (SOCF). Their specific complaint was a frequent one heard in correctional facilities: overcrowding.

SOCF, which had opened in 1972, was planned and built with 1,620 single-occupancy cells but began double-celling prisoners in 1975 as Ohio’s prisoner population increased. As with Laaman, the decision laid out key details of the court’s fact-finding investigation. These included the measurements and layouts of each cell, along with descriptions of spaces allocated for the prison’s ancillary programs.

Both parties agreed that, in general, the prison was “a top-flight, first-class facility,” and the immediate question concerned whether or not housing two inmates in a single cell constituted cruel and unusual punishment. The district court had previously concluded that double-celling did constitute Eighth Amendment violations, and one of the primary considerations in their decision was the fact that the prison was not being used as it was originally designed for. Another was that the reduced space allocated per inmate no longer corresponded to contemporary “standards of decency,” itself a key doctrine of Eighth Amendment jurisprudence.

The tone of the U.S. Supreme Court’s judgement overturning the original district court ruling was markedly different from that in the New Hampshire case, focusing almost exclusively on the idea that legal punishment was necessarily painful. “To the extent that such conditions are restrictive and even harsh,” wrote Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. in his majority opinion, “they are part of the penalty that criminal offenders pay for their offenses against society.”

Moving away from Bownes’s understanding of the prisoner as a whole person, the court seemed to define the prisoner primarily as a certain kind of person: a criminal convict. This attention to the prisoner-as-convict linked directly to what the court would deem appropriate in terms of their living conditions. Specifically, for Powell, there was no such thing as a “constitutional mandate for comfortable prisons.”

Expert testimony in the case referenced “contemporary standards” in the design of prison architecture, and the court accepted that, according to these standards, inmates at SOCF did not have enough space. However, they argued this was not sufficient proof of constitutional violation. For the court, the practice of double-celling did not meet what they called an “objective” metric of cruelty, constituting only a regrettable — but acceptable — discomfort to be suffered by inmates. Of course, the fiction of objectivity has always been part of law making. In Eighth Amendment law, this fiction placed ever greater burden on the plaintiffs to demonstrate harm.

Thus, by the time Pearly Wilson, an inmate at the Hocking Correctional Facility, brought an action against the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, grounds had been fully set for a ruling rejecting his claim that his Eighth Amendment rights had been violated. This ruling, Wilson v. Seiter, decided in 1991, confirmed the most restricted view of prisoner’s rights in the court’s history.

Presented with a similar set of facts as in the New Hampshire case argued fourteen years earlier, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia argued here that general prison conditions could not cumulatively amount to cruel and unusual punishment unless “they have a mutually enforcing effect that produces the deprivation of a single, identifiable human need such as food, warmth, or exercise.” Even more constraining was that a prison conditions challenge could only succeed by demonstrating prison officials’ “deliberate indifference.”

“Today, with increasing public visibility on the country’s carceral crisis, there is renewed pressure to address deteriorating prisons, and the way these buildings subject inmates to dehumanizing conditions.”

In other words, unfit prison conditions only constituted a violation of a prisoner’s constitutional rights if they were able to submit incontrovertible evidence that the prison, and its constituent buildings, deprived them of an identifiable (bodily) need — in addition to showing that officials in charge were in a “culpable state of mind” by intentionally allowing these poor conditions to bring harm.

Thus, by the turn of the twenty-first century, the court was arriving at very different conclusions regarding how evidence in the prison building could be levied by prisoners filing Eighth Amendment claims. In a significant departure from cases in the 1970s which confirmed that the prison building needed to support the state’s affirmative obligation to care, now the prison only needed to provide the barest of needs. But as with many legal standards, this radically constrained vision of prisoner’s rights is only stable if courts continue to uphold it. Today, with increasing public visibility on the country’s carceral crisis, there is renewed pressure to address deteriorating prisons, and the way these buildings subject inmates to dehumanizing conditions.

Figure 3. Louisiana State Penitentiary, death row complex, aerial view. Courtesy Google Maps, 2021.

The future of the Eighth Amendment (climate change and air conditioning)

Louisiana’s current death row opened in 2006. Located within the Louisiana State Penitentiary complex (a site often referred to as Angola), it comprises a 25,000 square-foot facility laid out in a cruciform plan and surrounded by a doubled wire fence, observation towers, and floodlights (Fig. 3). Notably, while some areas of the death row complex are air-conditioned, the inmate’s housing tiers are not. The fact that air-conditioned space is available for some of the occupants (the spaces occupied by the prison’s administrative staff) but not all (the spaces occupied by the inmates themselves) indicates that the complex was planned with some awareness of the climate: Louisiana is hot in the summer and getting hotter.

Prisoners’ cells in the death row building are distributed among four housing tiers, each containing between twelve and sixteen units. Metal security bars separate cells from the tier’s walkway. Otherwise, there are no apertures; louvered windows, open to the exterior, are located across the hall, approximately nine feet from each cell’s security bars. Inmates at Angola are to remain in these cells twenty-three hours a day. With no ability to self-regulate their environments, they are at the mercy of the institution to determine what constitutes necessities of life.

For Edith Jones, the presiding justice on the decision that granted Nathaniel Code relief in his Eighth Amendment claim, the crucial point hinged on an architectural understanding of the prison space, as the building provided proof of culpability as well as proof of harm (Fig 4).

According to the court, actions undertaken by the warden of Angola’s death row, Angela Norwood, showed conclusively that she knew that conditions inside the prison were too hot: she had ordered her staff to surreptitiously install cooling mechanisms at some point between when the initial complaint was filed, and when the state-filed appeal came to trial. That Norwood used architectural modifications in her attempt to ameliorate the interior conditions demonstrated the tight connection between the building and lived experience of those on death row; the court’s reliance on these details show how much the physical space of the prison was crucial in demonstrating “objective” neglect as well as the warden’s culpability.

As summer temperatures reach unprecedented levels, there is no doubt that more heat related Eighth Amendment claims will be filed. As global warming escalates, so too will these lawsuits continue to draw attention to prisoner’s rights — and to the architecture of incarceration. Given the highly unequal distribution, especially along racial lines, of the prison population in the United States, these cases beg the question: for whom among us will thermal comfort be available in an era of new extremes? And, how will a discussion of air-conditioning in this context — which necessarily frames the question as a distinction between optional luxury and necessary infrastructure — require us to re-assert the humanity of those imprisoned?

Citation

Haber-Thomson, Lisa. “Architecture and the Eighth Amendment: On Cruelty, Comfort, and Legal Personhood,” PLATFORM, January 24, 2022.