Unlearning, Part II

This is the second part of the conversation from the Unlearning Workshop organized by the Central New York Urban Humanities Working Group, Dec 9, 2020. For Part I follow this link.

Unlearning Pedagogy

Lawrence Chua: In this panel, Ana María León and Charles Davis II shared their experiences of teaching in a department of art history and a professional school respectively and responded to questions of unlearning pedagogy. How do educators begin to unlearn the conventions and structures of the disciplines and institutions in which we are embedded as architectural historians? What is the potential for reimagining the role of history courses in the larger curricula of departments, disciplines, or institutions with a renewed consciousness of the ways that imperialism and racial capitalism have structured disciplinary knowledge and academic and professional institutions?

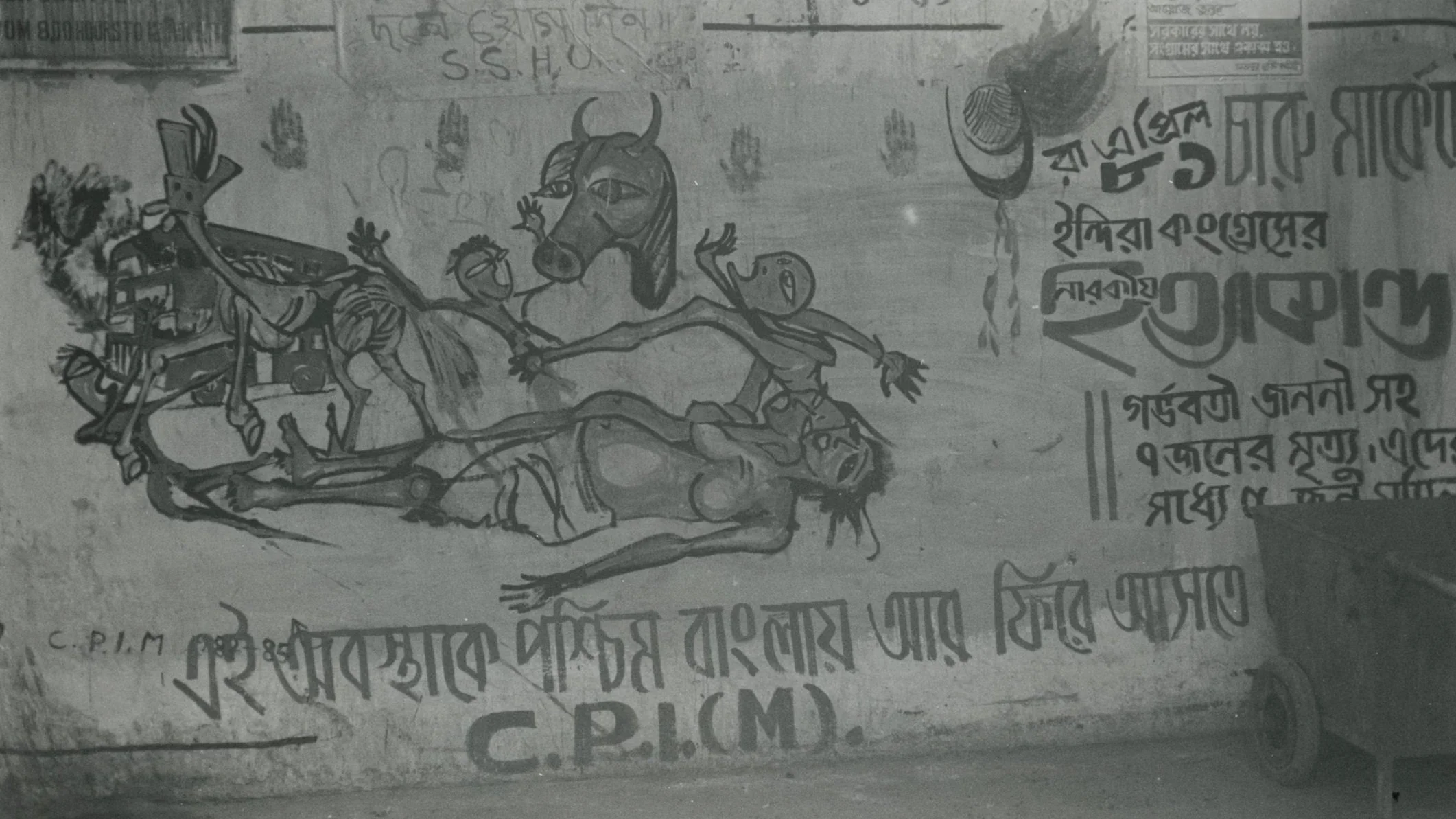

Ana María León: I'm joining you today from the land of the Huancavilca, in a territory known as Guayaquil, both before and after the Spanish conquest. I'm going to share with you this course, which finished as a methods course and I'll just briefly tell you that story. In her groundbreaking book, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay proposes that because photography is complicit with imperialism, then unlearning photography as a field “means first and foremost foregrounding the regime of imperial rights that made its emergence possible.” Similarly, unlearning the methods of architectural history as a field means, first and foremost, foregrounding the regime of imperial mandates that have made the emergence of architectural history impossible. A little tired of complaining, but not acting on the whiteness, privilege, and Eurocentrism of architectural history and theory—and I mean no action by myself—I realized that the only way to reject these markers of white supremacy was to foreground the construction of architecture itself as a white supremacist project and to offer alternative inroads into the methods needed to understand, resist, and dismantle this project. So, in the fall of 2019 I set out to teach a PhD seminar that did just that by borrowing methods from other disciplines in order to assemble a set of tools needed to write histories of spatial politics.

I go back again to Azoulay:

Unlearning imperialism aims at unlearning its origins, found in the repetitive moments of the operation of imperial shutters. Unlearning imperialism refuses the stories the shutter tells. Such unlearning can be pursued only if the shutter’s neutrality is acknowledged as an exercise of violence; in this way, unlearning imperialism becomes a commitment to reversing the shutter’s work.[1]

I organized the course in a way that looked specifically into the methods for writing these histories of withdrawal or refusal. We started by reading, on the first day of class, extracts from scholars, activists, and intellectuals reflecting on the position of the historian, the dangers of extraction, essentialism, and identification. I then divided the course into four big sections. The first section, “Systems of Domination” included coloniality, settler colonialism, and anti-Blackness as a constitutive component of settler colonialism. We then had a section on “Technologies” mobilized by these systems such as land dispossession, subalternity, and the subjugation of the body. Then we went on to a series of more recent “Systems of Control,” including nationalism and culture, labor, and neoliberalism. We had a final section that I tentatively titled “Escapes,” including revolution, infrapolitics, pedagogies of freedom, and self-determined imaginaries.

In each section, we examined reflections on the topic that most often came from outside architectural history. We had all these readings from outside architectural history and then we had case studies that came from within architectural history, such as the work of Paulo Tavares, but also the work of activists, such as the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust that address these problems in their own daily lives. This tackled two problems, often mentioned when discussing whiteness in architectural history and theory: the lack of sources and the lack of agents. It's both a multidisciplinary course on domination and control of the built environment and what these forces are as well as a series of case studies on resistance to this domination. I wanted to avoid having only the former take over, because I believe an excessive focus on forces of capital, racism, state oppression, and others tends to leave no space for escapes and ends up contributing to the problem as well. So while the last section on escapes is more explicitly on these ways out, every week we would look at case studies of how activists, artists, architects, historians, and other cultural producers labor to resist these various forms of oppression.

The reaction from my students was one of both enthusiasm and frustration. They were frustrated to see that they had never read these texts. The required methods seminar, which in the case of the first years, they were taking at the same time with mine, had absolutely no overlap with this course and that they had been completely ignorant of these discourses that they found very needed in their disciplines. In time, they shared with me that they had come to call my course their second methods course, one that had no overlap with the first one, and one that I did not set out to write but that it seems like I ended up teaching, with the advantage that it was an elective.

Charles Davis II: I'm here to talk a little bit about pedagogy in the context of a professional architecture school and I'll talk about it in two complementary ways. One way is to think about pedagogy as a form of practices, a form of standards and norms that are established for a student, usually in the sense that either these are universal principles of order and design or that they’re forms of professionalization in the actual field of architecture. But I want to also think about pedagogy as a set of beliefs and that these practices actually emerged from a set of beliefs and are founded upon those beliefs, many of which are very culturally specific. In the studios that I teach, I try to get my students to understand that the rules of form, space, and order that they've inherited through their design program and design education actually come from very specific political contexts and periods, many of which are associated with political systems of colonization, with forms of whiteness and white supremacy, and forms of political control that they are unconsciously passing forward because they don't know how to deconstruct their origins and to understand how these tools perpetuate ideas and beliefs through the practices.

I'm going to show you the work from a studio entitled “Playing Against Type: The Adaptive Reuse of Buffalo's East Side,” where we literally worked with developer housing in the area to think about the notion of typology in its most quotidian sense, which is the works of architecture that we inherit from a developer who's made assumptions about the person or persons who will live in that space. We looked at the Hamlin Park neighborhood in Buffalo, New York, originally settled between 1819 and 1920. It was established by developers using European-inspired architectural revivalist styles. We looked at the pattern books (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Lexington, 1927, Sears Home Catalog.

In the beginning of the semester, I was very conscious to associate architectural styles with the racial and ethnic origins of the people who originally settled in this location: German, Jewish, and Polish working class white ethnic Americans, and to date that back to this myth of American birth: the origin of America as really coming from immigration from Western Europe into United States and later subsequent ways of Central and Eastern Europe into the United States. Sometimes people will acknowledge that there were also Mexican and Chinese laborers coming into the US but usually because they were excluded, they had a limited impact on the built environment. At the same time I wanted students to understand that America and the continental Americas have a longer history that includes the presence of Indigenous Americans before the appearance of Europeans. It also includes enslaved Africans who, through the Great Migration, moved up north and settled in the very neighborhood of Hamlin Park that we were studying. I wanted my students to understand that we were critiquing the readymade explanations of the cultural importance of typology and how it operated in passing down certain types of ideas and beliefs. This understanding was important in order for us to recover some of the lost practices of the African American residents who were forced to live in European style housing without being able to modify them, partially because this neighborhood had become a preservation district and so there were restrictions against it. We looked at readings in architectural history and criticism, we looked at WPA writings of freed slave narratives, and we also interviewed residents in the area and worked with a community development corporation in order to figure out what it was that was missing, the spatial practices that were latent in these spaces architecturally because it could not be formally registered. Through a series of readings, seminars and colloquia, we started the practice by first trying to visualize what were the dissonances in these spaces, in the European style homes and the African American spatial practices that existed.

Here's a wonderful study that was done by a student on the practices of the black funeral homes in the area. (Figure 2) What he learned was that these homes actually became hubs within the black neighborhoods, not only because they dealt with life and death and the whole natural process of living in the space, but also because of the wealth and privilege of the person who ran the funeral home. They were able to actually participate in the Civil Rights Movement in a way that was undetected by others (Figure 3). So they would have meetings in this space. The owners of the funeral home would post bail for those who were arrested during protests. There were ways that so-called “subversive” activities occurred in the spaces that were unseen on the outside. When he took existing advertisements of spaces like the parlor room where the funerals originally took place and also old paintings by Norman Rockwell and other Americana types of folk art, and overlaid that with the information that was missing from history to give us a sense of what should be a fuller accounting of these neighborhoods.

Figure 2. Nicholas Eichelberger and Shashi Vardun, Preliminary collage, Black Funerary Practices, Playing Against Type.

Figure 3. Nicholas Eichelberger and Shashi Vardun, Preliminary collage, Black Funerary Practices, Playing Against Type.

After understanding these issues, my students were asked to experiment with different types of existing building typologies and to adjust them to formally register the missing information about Black space that was in these locations (Figure 4). What was interesting is that these are the kinds of houses that were typically there, ranging from the American foursquare to the bungalow to colonial revival forms and the Buffalo double forms—all European American inspired spaces—and we read these house types in conjunction with studies like the Yard People, which is a short documentary on the ways that middle class Black Americans would create an informal use of space across backyards literally connecting them to create a network within the neighborhood. Nothing would be modified physically but spatially there was a kind of complexity to what was happening there.

Figure 4. Madeleine Niepceron and William Sokol, Proposed Changes and New Housing Typology, Dissonance and Racial Trauma in Black Homeownership, Playing Against Type.

This last project that I'm going to show you here, takes the idea of entrepreneurship that was used in the spaces, particularly in the doubles, and transforms it into a kind of incubator for the informal works of braiding that this particular resident was engaged in. Doubles were rental spaces usually owned by someone on the ground floor and who then rented out the top two floors (Figure 5). They created a plan of phasing where the braiding salon could be expanded to not only include a part of the home, but an entire floor. Instead of renting the space to someone, they could turn it into a business. This would create both a kind of incubator space on the ground floor, and then a space for informal barbershops for people who were trying to build up capital to create their own barber shops in the middle space (Figure 6). What I thought was really interesting was that this student went to the task of trying to critique Semper’s nineteenth-century notion of tectonics by writing the practice of braiding into the kind of material practices that were left out of that particular record. So, at the spatial level, at the tectonic level, with structure and aesthetics, they were trying to weave as much as possible to re-semanticize the kinds of architectural strategies that they've inherited to fit this culture (Figure 7).

Figure 5. Jenna Herbert and Mira Shami, Proposed Changes and New Urban Infill Typology, Black Hair and Entrepreneurship, Playing Against Type.

Figure 6. Jenna Herbert and Mira Shami, Preliminary Collage and Diagram Studies, Black Hair and Entrepreneurship, Playing Against Type.

These are some ways of thinking about how pedagogy can be made much more transparent for students through the process of critique and then giving them that vocabulary to allow them to then think about creating things and forms that are specific to the people that they're actually serving.

Lawrence Chua: So much of liberatory pedagogy centers around unlearning hierarchies that are implicit in the classroom or the studio—which is perhaps the most hierarchical but also collaborative space of learning that we have. I'm wondering whether the unseating of hierarchies was important to you, and how we might begin to move away from the hierarchies that structure learning and instead begin to emphasize that collective nature of what Stefano Harney and Fred Moten have called “Black study” as a mode of thinking with others, instead of these passive forms of individualized learning that are expected in institutions that are essentially designed to reproduce the status quo. How does one move beyond this prescription for repair and imagine instead a more radical connectivity?

Ana María León: One of the comments I remember from student evaluations was that the course felt more like a reading group: when some clarification was needed I always stepped in and helped out. It is commonplace to say, each student is in charge of leading one session, which is very much a trope of advanced seminars, but I really work at framing it so we are reading and learning and processing these texts together. That labor of framing the classroom is part of my politics. I didn't speak to the format and those modes of engagement in terms of form in teaching, but rather to the content, but certainly both things are equally important. I set out those terms on the first day of class as well as my own positionality, our different types of shared privilege, and the need for all of us to be there at the table.

Charles Davis II: Usually, I teach history courses, history surveys, and research seminars that allow for me to advance and deepen my own research, initially on the critique of whiteness in our discipline and now, the recovery of Blackness in our discipline. Moving over into the studio space, I find that the way the dynamics of authority work in that space are slightly different. In one person's vision of the studio, it may seem like a liberating space, but actually it can be very coercive. You have the Beaux-Arts legacy, where the patron is at the head of the class and everyone is following their lead. There are a lot of unstated standards that are passed through with the use of precedents, with the kinds of taste-making that's occurring. My very first strategy is to talk about that stuff and to put it on the table. I want people to say what is un-said, so that they understand the practices and the processes of coercion and they can subvert them for their purposes. Another thing that that I try to do, at least in the studio dealing with houses and housing and the ways that identity is expressed in that kind of intimate context, is to elevate the personal archive as an archive that is just as authoritative as typology and the things that we inherit from architecture and from other designers and history, and to treat them as equal things. The cutting apart of the outside to allow for new views or to allow for new expressions of different types of spaces is purposeful. It's a way for me to guide my students and bring in the oral archive in conversation with the inherited architectural archive. In a way, I feel like this is usually taught as a graduate studio, but I feel like it should be a freshman studio or sophomore studio. It offers a way of understanding how students come from the spaces that they think that they know and asks them to interrogate them in new ways. Students then bring oral archives to it to understand the different types of discourses that are at work on our built environment. It's really about legibility, giving the students a vocabulary, and then a set of strategies that are subversive, so that when they go off into other spaces--if they remember—they reuse those strategies. They're articulating the coercive discourses and making a space for themselves, if they have to. Particularly for the students of color that I have, I find that this is a studio that they shine in versus other studios and they start the conversations about who thinks what in the program, what faculty members have what bias versus another bias. And it's okay to talk about that in this space. So for me, that's what's liberatory about at least the way that I run that particular studio.

Lawrence Chua: Paola de Martin asked, “How important is speed in the process of unlearning? Do we have to be fast learners to catch up with all that we lost? How important is slowness, compromises, political activism? How do you deal with a different materiality of time?” I think Ana María started to answer this, but maybe she can elaborate her response.

Ana María León: Everyone should learn at their own speed but I consider teaching as a site of political struggle. I consider it my obligation to provide my students with a framework and a space for learning at their own speed. So, sometimes they won't get to everything. But they can carry that framework with them, they can carry the readings with them and continue reading. But my obligation as a teacher is to provide that work in that space.

Charles Davis II: I don't think I give my students skill sets. I think in some studios it's all about representational skills and the kind of conventions and things that you can reproduce in other places. For me I think it's really strategies of interrogation. It's a way of understanding both the site and the context in a deep way and what one can contribute to that. I'm hoping that the student learns a strategy and then they reapply it elsewhere. Once they understand how that is done, for me, it's like a burr on the brain that is stuck there and then you continue doing it again and again. I'm hoping that it's not just slow or fast, but it's continual, that unlearning is a continual process. You're always unlearning. You're always actively and dynamically trying to adjust the situations. I tried to model that for my students so that it's an expectation. I can tell you for a fact that when I go visit them as a critic in other studios, they expect that. They know how to respond to those kind of questions because it's already given as an expectation within the curriculum.

Ana María León: This course that I put together came out of reading A Third University is Possible. I teach in a First World university and la paperson argues that a third university, a university of countering the hegemonic settler-colonial First World university, is possible and it's embedded within that First World university, acting in opposition to it. I assign this reading in that course and we speak against the university from within the university. These spaces of resistance will also involve an awareness that our pedagogy, no matter how well meant it may be, is always ultimately politically in resistance to some of the very spaces in which we are employed. Which is to say, it's all the more reason to use those spaces against that university itself.

Notes

[1] Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (New York: Verso, 2019), 7.