Archives of Empowerment? Unearthing Afthereta’s Architectural Documentation in 1970s Greece

Before the 2008 economic crash which brought about the Greek state’s implementation of steep new taxes on real estate and the auctioning of thousands of foreclosed houses, the ability of people to improve their lives through homeownership epitomized Greek national identity. Architecture played a significant role in this mindset, privileging individual efforts and savings for owner-occupation. I examine this relationship in a recent essay and book, which analyze the unexplored history of U.S. housing aid to Greece between 1947 and 1951, focusing on how support for self-built housing served American anti-communist objectives.

It was under this agenda that architects and planners Jacob Crane, American, and Constantinos Doxiadis, Greek, conceived a hybrid architecture to address Greek aspirations for modernization that also incorporated available local resources and traditional wisdom. This architectural conception was a precursor to later “self-help” schemes in so-called developing countries, promoted and financed by the United States and the United Nations.

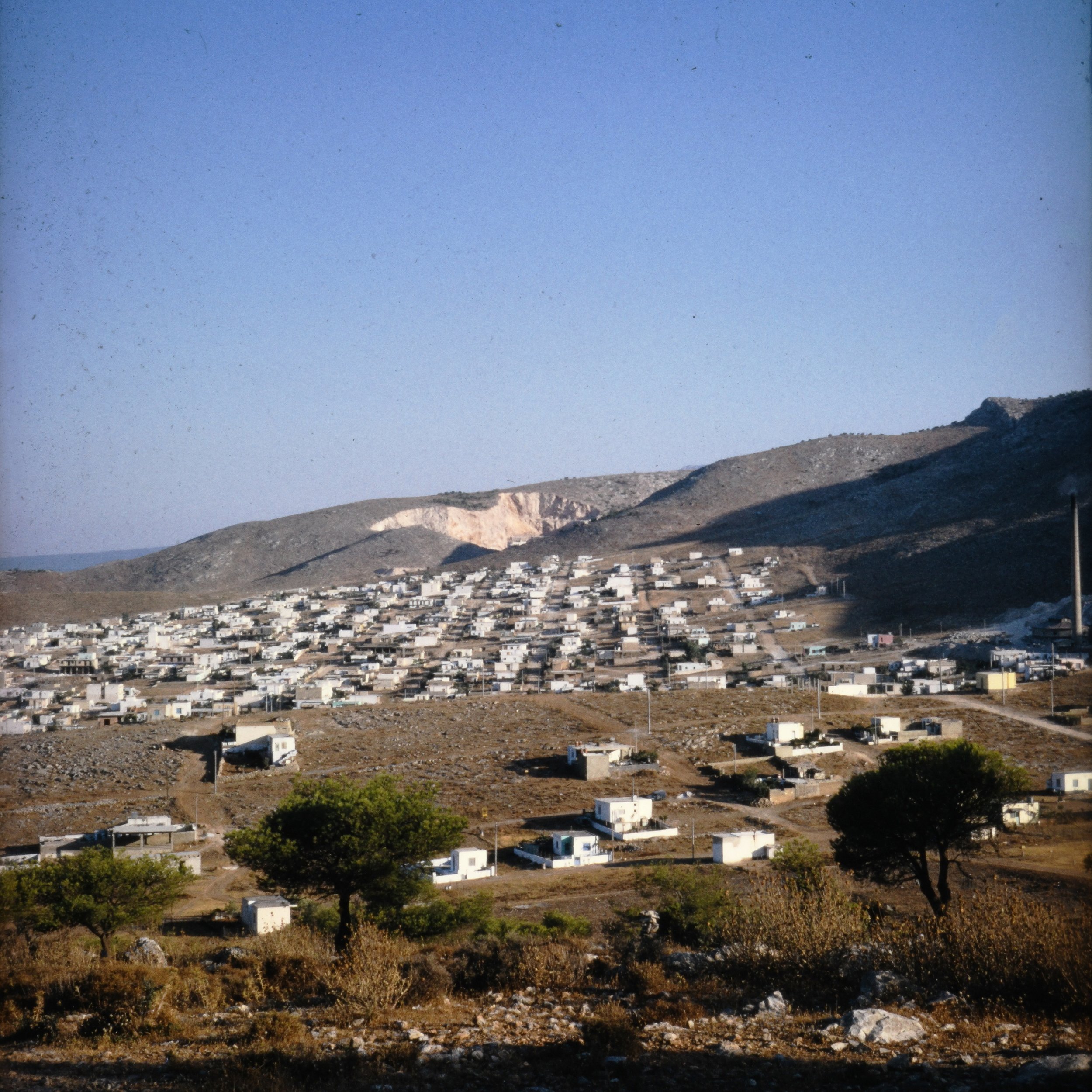

Figure 1. Panoramic view of the afthereta at Peristeri in 1968. Reproduced with permission of Aristedes and Maria Romanos.

Scholars who have studied the history of self-help housing schemes in the Global South like Ijlal Muzaffar, Farhan Karim, and Helen Gyger have shown that self-building functioned as a stepping stone to modernization. This is true not only in terms of societies’ transition, through their own effort, from the traditional ways to modern, consumerist lifestyles, but also in that housing became a stimulator of private investment.

In the case of Greece, this kind of hybrid architecture (half-traditional, half-modern; half-state sponsored, half-owner-built), which served as a substitute for public housing — something the Americans saw as nurturing support for communism — was considered successful by its promoters in that it effectively drove private savings into the market, leading to an unprecedented period of economic growth that lasted for decades.

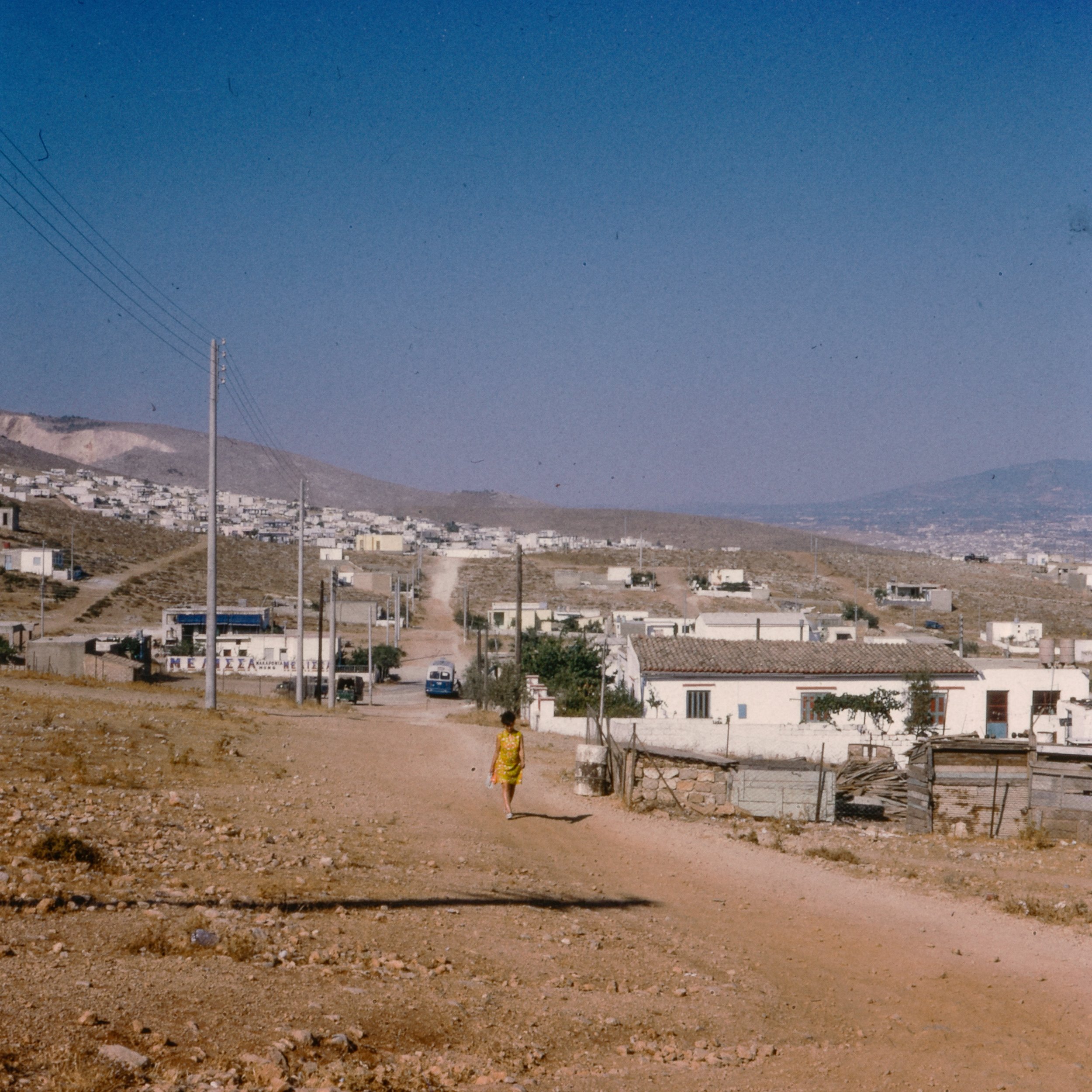

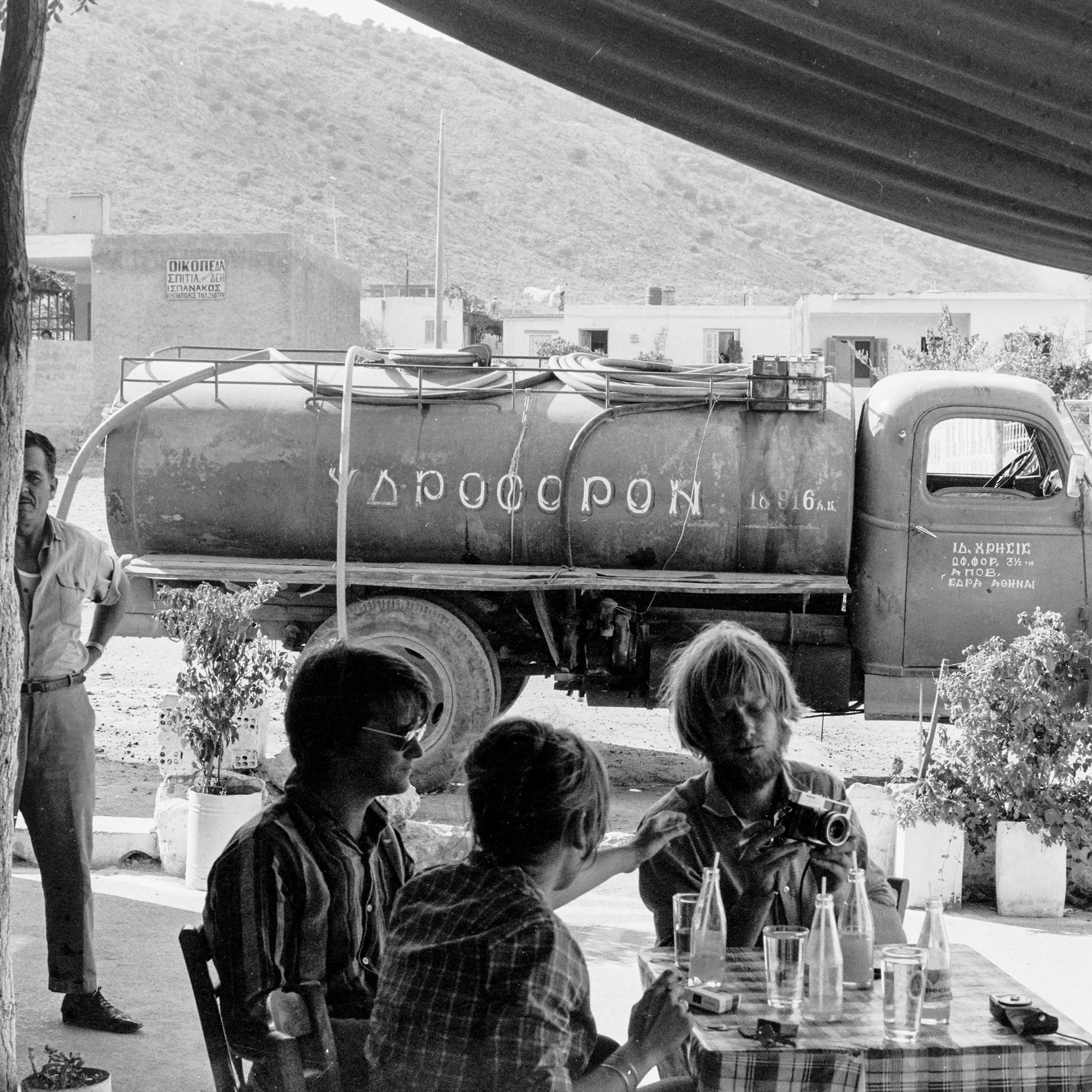

As a direct consequence of U.S. and Greek development and anticommunist policies, self-built housing became the norm by the late 1960s. This included construction in semi-legal settlements commonly known as afthereta, which proliferated on the outskirts of Greek cities, particularly Athens (Figures 1-5).

However, during the military dictatorship of 1967 to 1974, the well-established collective mindset of self-effort and savings was threatened as the regime prioritized large capital investment, foreign and local, in major infrastructure and industries, including housing, and began bulldozing afthereta.

Residents protested (Figure 6). So did architects. The professional organization of Greek architects, the Association of Graduate Architects (SADAS), demonstrated solidarity through documentation, publicity, and other forms of political activism, even going so far as to physically confront the police (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Residents grieve after the authorities demolished their house at aftereta in Kamatero (1973). Reproduced with permission of Aristedes and Maria Romanos.

Figure 7. The AGA shows solidarity at the squatter settlement at Perama (1974). Image published at the February 1975 volume of the Association’s Bulletin. Reproduced with permission by the Archives of the Technical Chamber of Greece.

The historical documents regarding this activism, which lasted from the late 1960s to the late 1970s, shed light on a diverse and substantial group of professionals whose activities challenge the celebrated author profile of Western modern and postmodern traditions, as well as the role of the development expert who, like Doxiadis and Crane, represented national agencies and international organizations such as the UN. Operating on a local scale disconnected from national and global decision-making centers, architects made a substantial critique of modernism and explored novel forms of professional praxis, forging a new place in a changing discipline.

Interest in afthereta was not merely about supporting a local movement, then. It was linked to, and influenced by, contemporary debates, local and global, regarding the evolving roles of architecture in a rapidly urbanizing world. These debates involved prominent public figures, politicians, and practitioners working on self-help housing and exploring the potentials of squatter-settlements.

“Greek engagement with self-building sheds crucial light on a moment when architects around the world strived for political relevance.”

Doxiadis and his office, Doxiadis Associates, based in Athens, along with the English-language journal Ekistics, which he founded with British planner Jacqueline Tyrwhitt in 1955 with the aim of exhibiting pioneering research and expertise on “human settlements,” were central to this scene. Early on, in November 1964, British architect John F.C. Turner, whose ideas influenced the World Bank and the UN’s Habitat conference to support squatter settlements as means of capitalist development, delivered three lectures at Doxiadis’ Athens Technological Institute.

Figure 8. The poster of Romanos’s course at the AA. Reproduced with permission of Aristedes and Maria Romanos.

Interest in afthereta was also stimulated by other development experts who visited Greece and Doxiadis Associates, like Crane and Charles Abrams, as well as the longer local legacy of reconstructing rural settlements in Greece. It is not by chance that the first architectural study of an Athenian unauthorized settlement was submitted by Doxiadis employees (to a competition organized by Ekistics under the general theme Greek architectural tradition). Tellingly, this late-1960s valorization of self-building insisted on the importance of traditional flair, contributing to the national mindset that Greeks were inherently owner-builders.

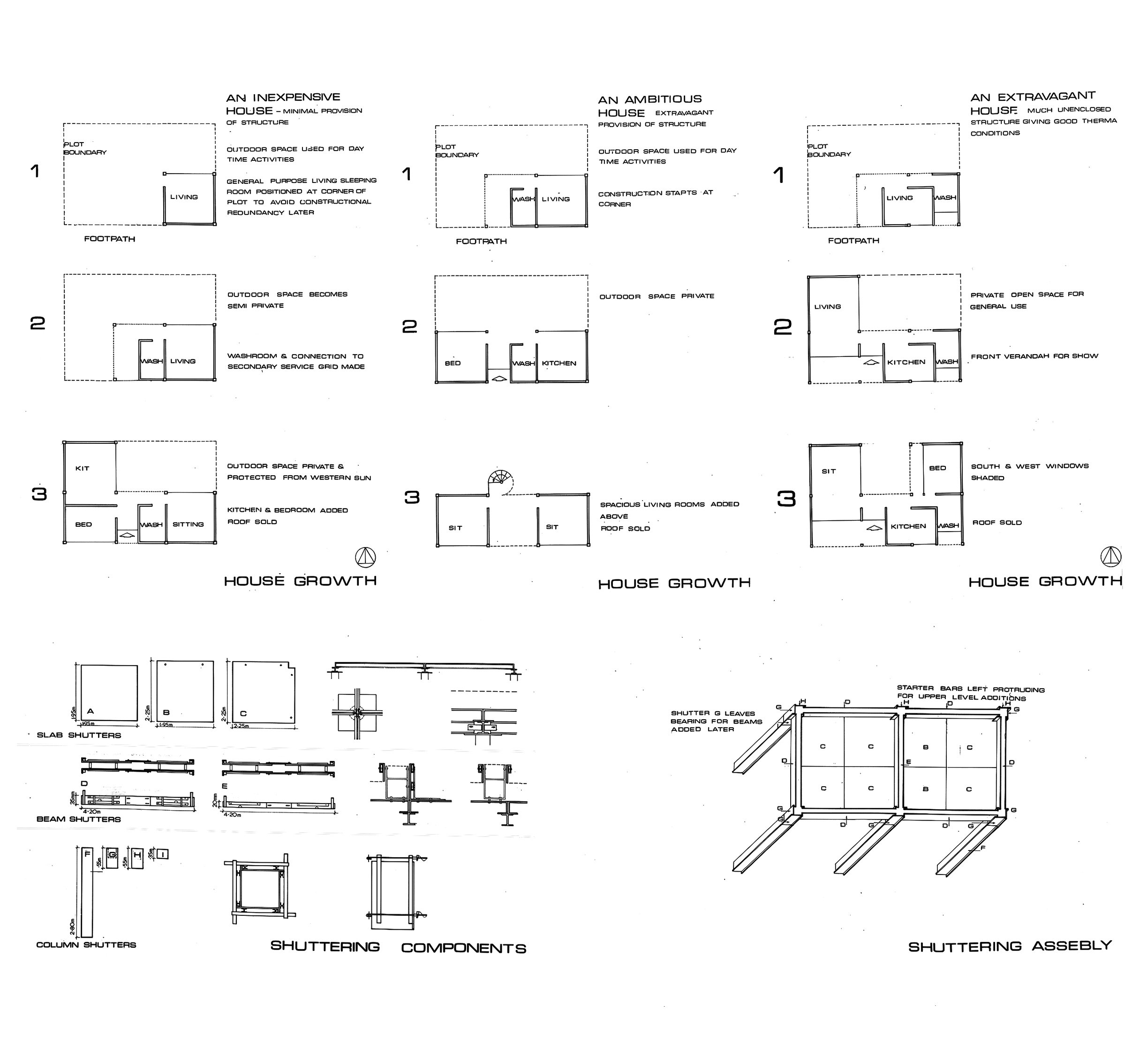

Greek architect and planner Aristedes Romanos was particularly important in this professional reorientation. Under Turner’s influence, Romanos began studying afthereta in the late 1960s. His studies soon made an international impact. His chapter in Paul Oliver’s counter-culture milestone Shelter and Society (1969), which included also Turner’s and Mangin’s chapter on barriadas, introduced Greek afthereta to a global audience as a vital alternative to public housing. From 1969 to 1971 Romanos taught at the Architectural Association in London, actively participating in shaping pedagogy, taking also part in Otto Koenigsberger’s influential Department of Tropical Architecture, at a time when the department was expanding its areas of interest and teaching, even establishing a one-year postgraduate course (Figure 8).

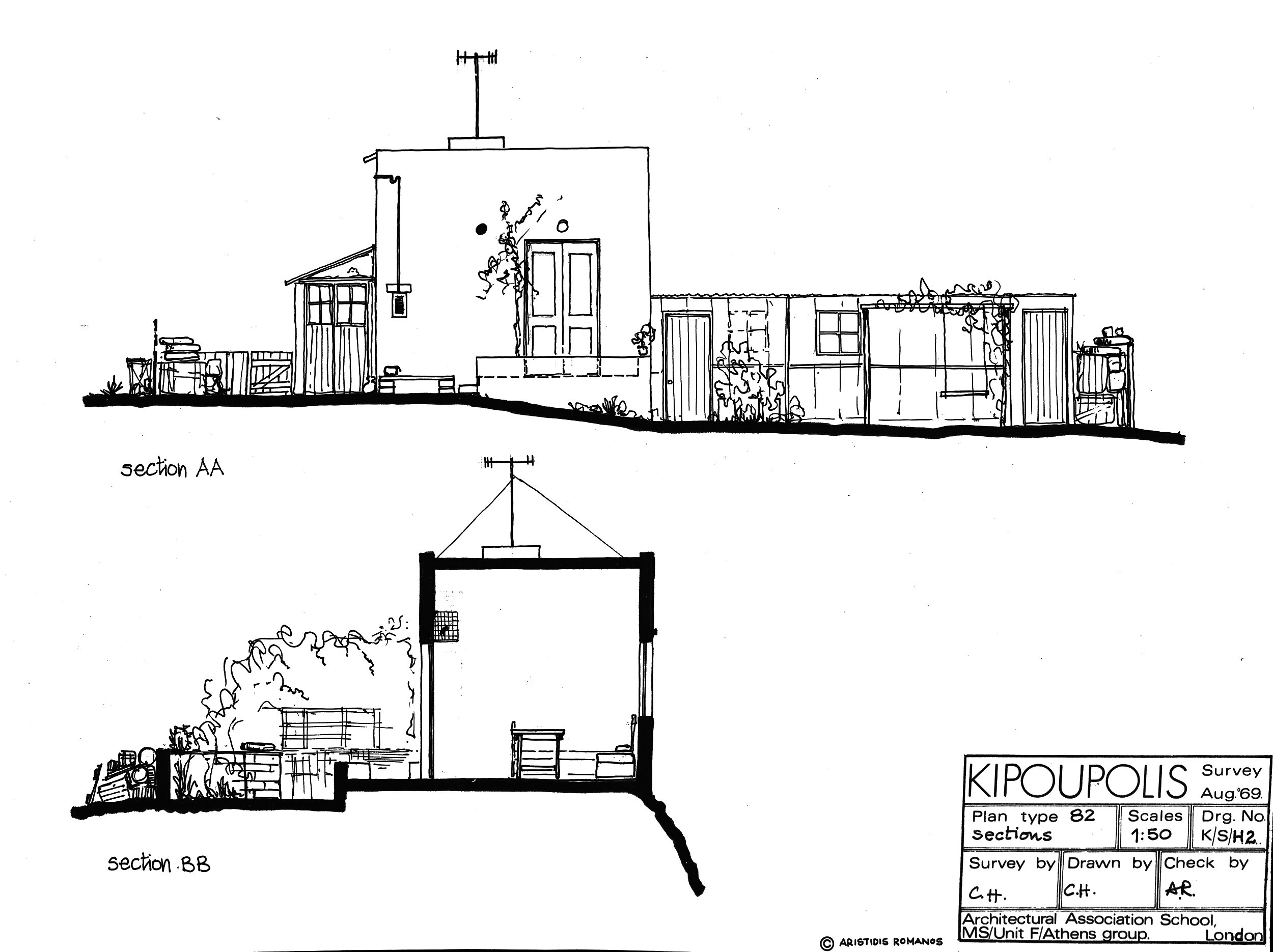

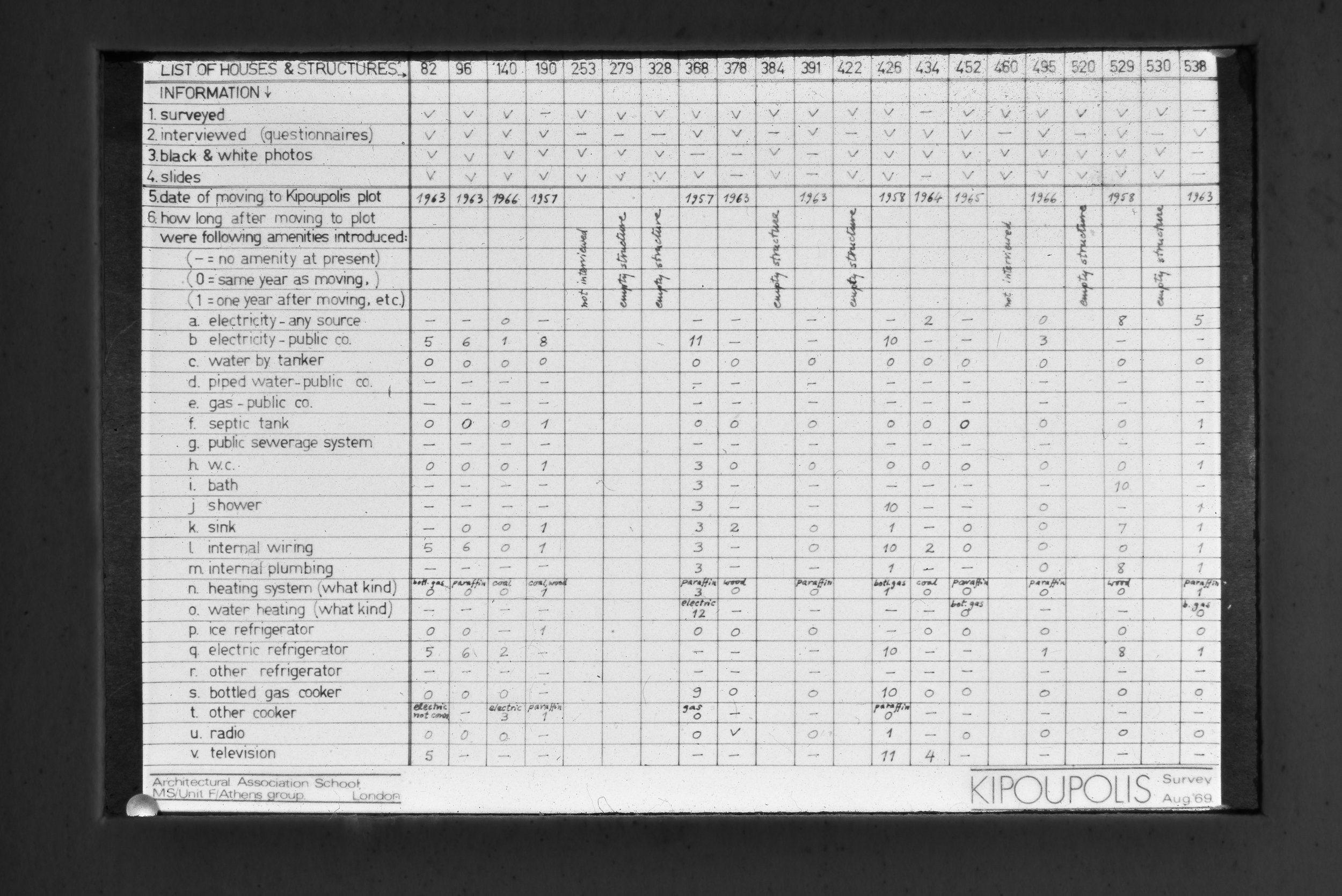

Perhaps most importantly, the material produced by Romanos’ two on-site summer courses on afthereta, which garnered substantial attention when exhibited at the AA Gallery’s Front Members’ Room, contributed to an expanding of global archives on self-building (Figures 9-13). Indeed, archiving self-built housing soon became institutionalized, especially following the World Bank’s endorsement, in 1974, of squatting on account of its market productivity, and the UN’s Habitat conference, in 1976, which linked squatting to flexibility and upward mobility.

As all this unfolded, fueled by the global architectural community’s desire to guarantee that the profession remained involved in addressing the housing problem, Greek local specificities were eclipsed by overarching narratives. Regardless of the centrality of the archives produced by Greek designers, Greek engagement with self-building sheds crucial light on a moment when architects around the world strived for political relevance. Unearthing such archives isn’t just about providing a new glimpse into the history of urban settlements. It’s about illuminating architecture’s professional evolution and stakes after the dissolution of the welfare state and its vanguard status.

CITATION

Konstantina Kalfa, “Archives of Empowerment? Unearthing Afthereta’s Architectural Documentation in 1970s Greece,” PLATFORM, June 19, 2023