Walking the Field in Milwaukee

During the past few weeks, relentless voices of young, diverse, and determined marchers have taught us a few lessons in place and place-making. Long phalanxes of protestors chanted as they snaked through predominantly white neighborhoods of Milwaukee’s segregated Eastside like a throbbing organism. People joined the march, individuals left, streams merged, and groups drifted away. Sound surged in waves. A collective chant of “walk with us” started in the front rows and syncopated backwards. This message of minority voices and perspectives was delivered to the majority white Eastside audience loud and clear. Many white residents joined the crowd, but, some others demonstrated fear. As the crowds moved through the clean streets, past manicured lawns, private trucks and police vehicles blocked off side streets and channeled the crowd to move along Oakland Avenue. Window blinds parted and fearful faces peeped out; some fled to the white suburbs to avoid the demonstrators.

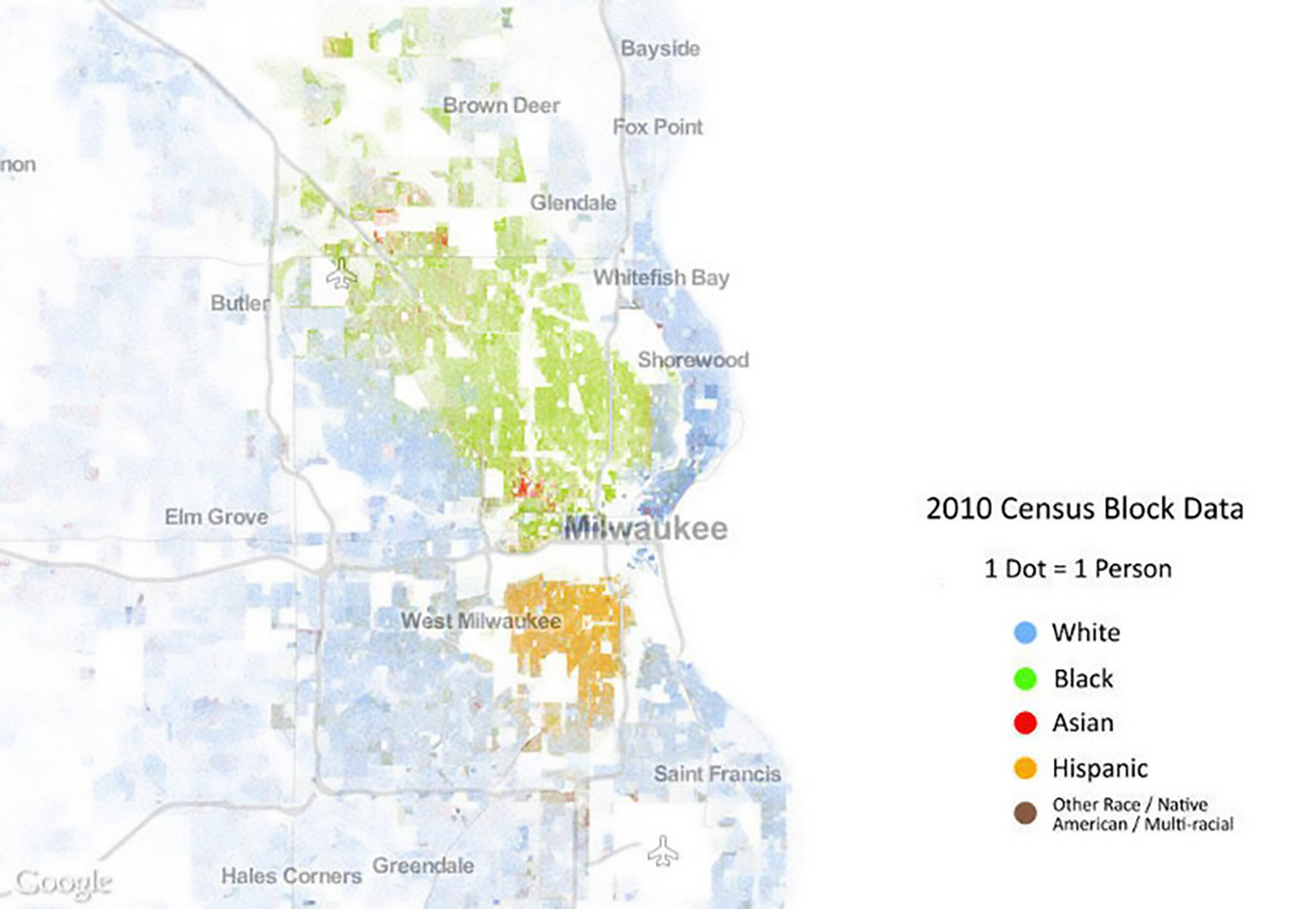

Black bodies in large numbers in Milwaukee’s Eastside is not a regular sight. This is because the city is segregated. Black and brown communities are separated from white neighborhoods due to a long history of racially coded real estate practices, unfair urban policies, and purposeful geographical redistribution of resources (Figure 1). But that history is lost on most Eastside residents. The everyday built environment of Milwaukee may indeed be the result of a century-long series of racialized practices but is also one where these inequities are normalized and concealed. It is only occasions such as this, when the façade of normalcy ruptures with sights and sounds of “Black Lives Matter,” that the abnormality of a segregated city becomes obvious to everyone.

Figure 1. A “Racial Dot Map” based on census data from 2010 shows a segregated city. © 2013, Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (Dustin A. Cable, creator).

Scholars of the built environment are complicit in ways injustice is concealed within urban spaces because our methods of analysis and our ways of seeing contribute to this tale of two cities. Writing about climate change, Amitav Ghosh explains how in a modern realist novel, “the very gestures with which it conjures up reality are actually a concealment of the real.” This holds true for architectural analysis as well. Despite reminders from Dolores Hayden, Gwendolyn Wright, and Dianne Harris, our methodological toolbox—the ways we see, document, and analyze buildings—have become modes of concealment, preventing us from noticing Black and Brown histories in our everyday urban environment.[1]

Buildings offer a false sense of permanence of presence, ownership, and meaning. Even as time passes, users change, and a patina of age weathers the scene in front of us, architectural historians return to origin-stories of builders, patrons, materials, styles, and ornamentation. Conflicting narratives of how different people interpret and experience this built world remain the domain of those other scholars: cultural historians.

“Who built these buildings and landscapes?” we ask. “Whose cultural values are imprinted in the façade ornaments and interior layouts of Milwaukee’s buildings?” In the context of Milwaukee’s Eastside and Northside, the answers predictably describe two areas distinguished by social class.

Between 1900 and 1925, working-class homeowners, predominantly of German origin, moved from the urban core into Northside neighborhoods in search of well-paid jobs along a growing industrial corridor. Well-crafted front façades served as modes of class distinction and bootstrapped upward mobility. The narrow tree-lined streets were social spaces where residents walked to their nearby jobs or shopped in a local main street. Albert Kennedy, in his study of working-class communities in Boston between 1905-1914, called such neighborhoods, “zones of emergence.”

In contrast, the history of the Eastside “Gold Coast mansions” overlooking Lake Michigan and Prospect Avenue offers a nostalgic retelling of “prosperous businessmen and professionals [who] built the most imposing homes of their time.” Historian John Gurda writes, “Some were simple, almost chaste, in their elegance, while others would have satisfied the appetite of any Eastern tycoon. All symbolized success.”

Today’s descriptions of Milwaukee’s built environment continue the story of two distinctly different urban scenes: one of the manicured Eastside and the other of the decrepit marginalized Northside. The City’s tourism office disseminates brochures, maps and pamphlets celebrating some neighborhoods while erasing the very existence of others. For instance, the Visit Milwaukee Map, produced by the City of Milwaukee’s Convention and Visitor’s Bureau marks the historical neighborhoods of the East Side, rich industrial architecture of the Menomonee Valley, and the cultural diversity of Downtown, but consistently ignores the disinvested, poor and Black Northside sections of this town.

Milwaukee’s architectural and urban historians draw a clear timeline that leaves out Black and Brown histories. Accounts of vernacular homes examine how valorous twentieth-century German and Polish builders reproduced duplex apartments in order to assimilate into the American (read Anglo-American) mainstream. Seen from the archives, Milwaukee’s architectural heritage narratives conclude with the golden industrial age settled by mostly German and Polish immigrants. These historians find no need to describe how African American, Hmong, and other minority groups adopted and adapted these buildings since the middle of the twentieth century. Their narratives follow a long disciplinary tradition that focuses on singular historical moments, marking the period when these buildings were built as significant.

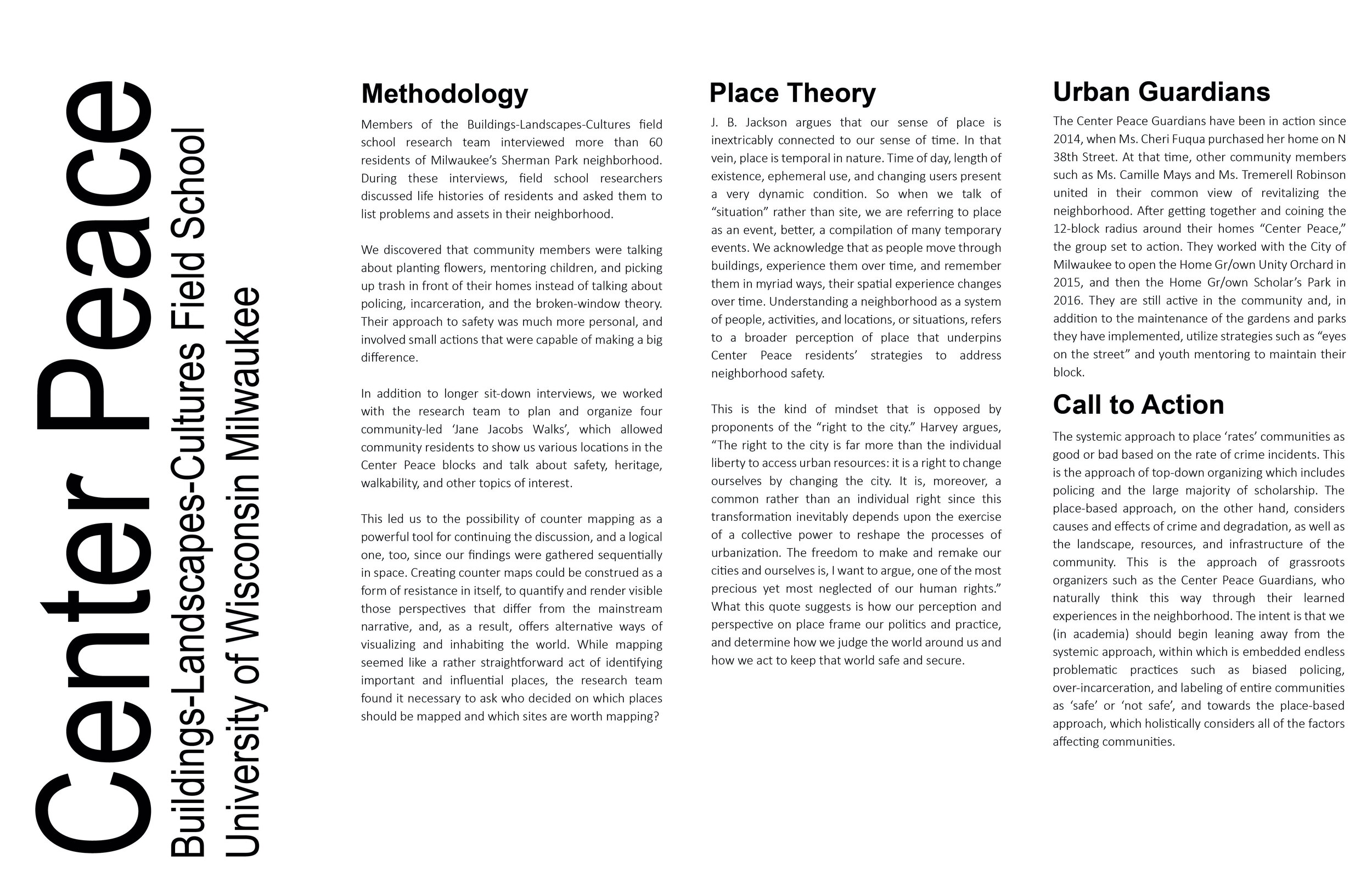

When historiography is complicit in the effacement of Brown and Black voices, we find it necessary to examine how our methods of data collection and interpretation promote and perpetuate this erasure. Since 2012, my students and I have collaborated with residents of Milwaukee’s often-ignored and marginalized Northside neighborhoods to learn to interpret this world, less known. At the Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School project we set out to unlearn years of architectural training (Figure 2). We experiment with community-led walks to begin our research instead of a visit to the archive or an analysis of a building. Archival and material culture analysis remain valuable methods that we return to after our initial community-led fieldwork.

Figure 2. Image of a walk led by Tremerell Robinson. May 12, 2018. © BLC Field School.

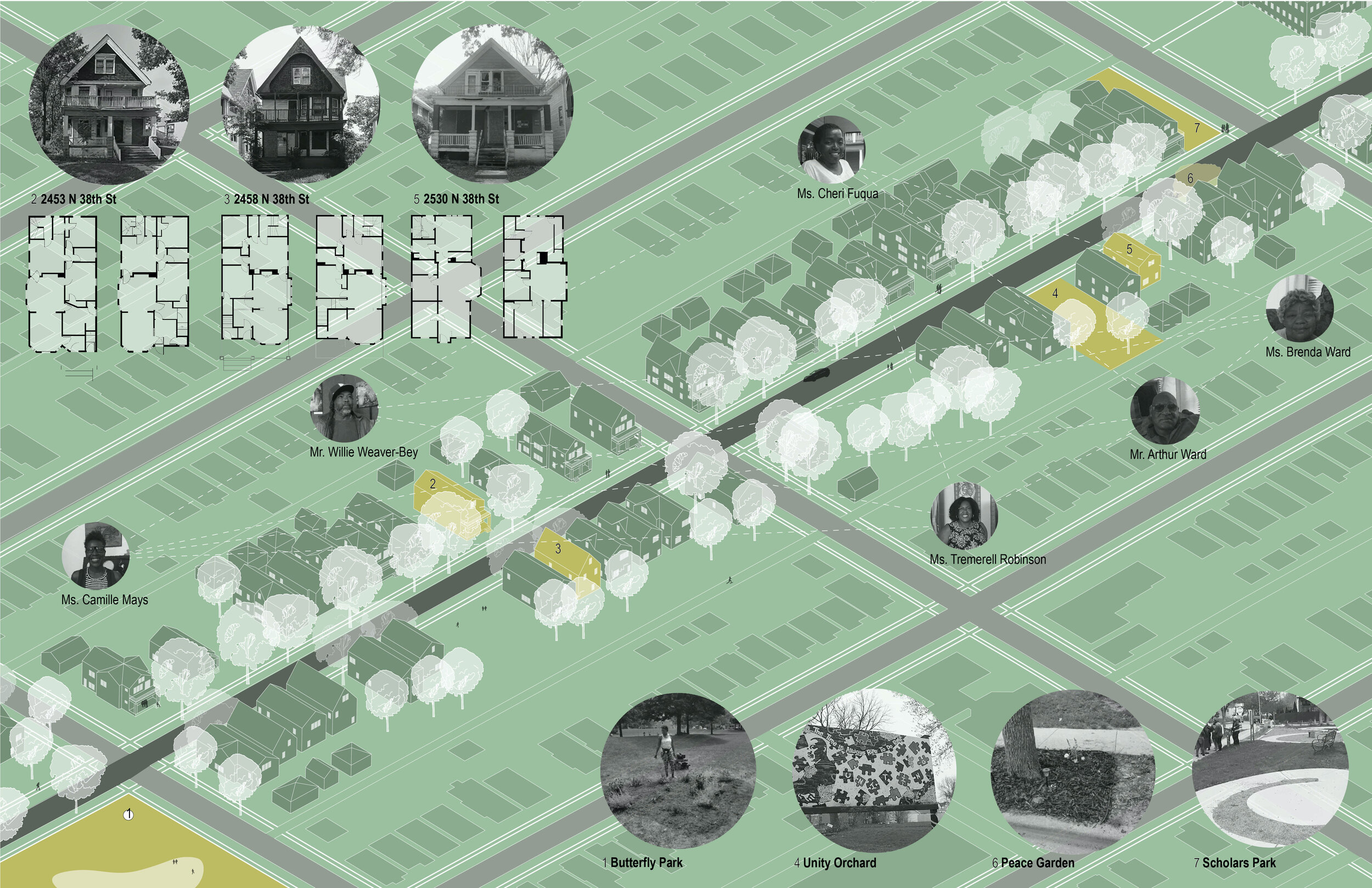

Take the example of a tour in the summer of 2018, when my students, community members, and I, stood at the intersection of Wright Street and 38th Street, close to the site of the infamous Sherman Park uprising. Just two years ago, police had shot dead 23-year-old Sylville Smith blocks away from where we were standing, and the African American community rose in revolt. New York Times wrote, “The burning buildings, smashed police cars and scuffles between police officers and angry protesters on Milwaukee’s north side over the weekend might have seemed like a spontaneous eruption. But for many in the city’s marginalized Black community, it was an explosive release decades in the making.”[2] We pondered about the ominous prognosis in the New York Times article. How can the impact of this history be reversed when the city’s workers and police regularly outrage the dignity of residents?

The neighbors seemed more optimistic. They told us that they have since rechristened this area as “Center Peace,” an island of calm and peacefulness amid a sea of structural racism, institutional neglect, and grassroots revolts. They described a vibrant community made of engaged neighbors, urban gardeners, and intergenerational families. Yet, signs of poverty and disinvestment appeared before us: boarded-up and foreclosed buildings with ominous red crosses representing fire risks, city-owned vacant lots with overgrown grass, potholes, sidewalks filled with fast food wrappers, and broken beer bottles filled our visual field. What the residents told us was not what we saw in front of us (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Annotated image of 38th Street between Wright Street and Clark Street. Image adapted from Google Maps. © BLC Field School.

What we saw reiterated culturally produced perceptions, not the lived reality of this place. This epistemological contradiction is at the core of how inequality and injustice is perpetuated and established in the everyday world of Milwaukee’s Northside. Jacques Rancière uses the term, “the distribution of the sensible” to refer to a guileful aesthetic order, with implicit rules and conventions, that reproduces a “division between the visible and the invisible . . . the sayable and the unsayable.”[3] To us, this environment was a decrepit version of the nostalgic twentieth-century zones of emergence that historians had described to us. We saw dilapidated clones of spaces we experience in the Eastside. Our readings of declension were based on symbolic meanings, visual syntax, and an aesthetics of dereliction that were ingrained in us. But the problem lay with us, our vision, our way of seeing, and our modes of interpreting the landscape.

Figure 4. BLC Field School students interview community residents in the basement of the Greater Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church, Fall 2019. © BLC Field School.

Figure 5. BLC Field School students help community members erect a painting made by a local artist on a pocket park. © BLC Field School.

Our community partners showed us alternative ways to “read” the material world of their neighborhood via entangled stories in which the personal and the communal, past and present, permanent and the ephemeral, visible and the invisible are intertwined. They retraced their daily path to describe, what an ethnologist would call, their “home range.”[4] We mapped this reticulated landscape made of homespaces, workplaces, playgrounds, sidewalks and everything in between. Boarded-up buildings, empty lots, spaces between properties, sidewalk verges and median strips appeared as sites of heritage. Sidewalks and porches held generational memories of resistance against police brutalities, crime, and joblessness.[5] Empty lots and roadside gardens were described as sites of memory. Boarded-up, ghostly homes offered stories of a losing war against absentee landlordism and housing injustice that began with the flight of white neighbors to the suburbs after World War II. Porches and living rooms of certain homes were referred to as community gathering grounds, a historical motif from households remembered from the Deep South (Figures 4 – 7).[6]

Figure 6. Community members play with a kit of parts designed by Taryn Singh to explain how residents can adapt a mixed-use duplex building to suit their needs. © BLC Field School.

Figure 7. Buildings tell us stories too. BLC Field School students documenting homes in Sherman Park, Milwaukee. © BLC Field School.

Ethnographic walks encouraged co-theorizing, a method we adapted from collaborative ethnography. Joanne Rappaport describes co-theorizing as a form of collaboration with one’s interlocutors, that transforms “the space of fieldwork from one of data collection to one of co-conceptualization.”[7] Co-theorizing takes a long time. Our primary fieldwork occurred during summer as part of a public history field school. But engagement with community members stretched into fall and spring semesters with community-led walks, storytelling workshops, art, theater, performance events, and construction projects where scholars worked alongside community residents to build gardens, street furniture and sheds. We also held art events and community barbeques. These “events” gathered citizens and scholars around community-identified sites of heritage for further conversations around collective civic actions.

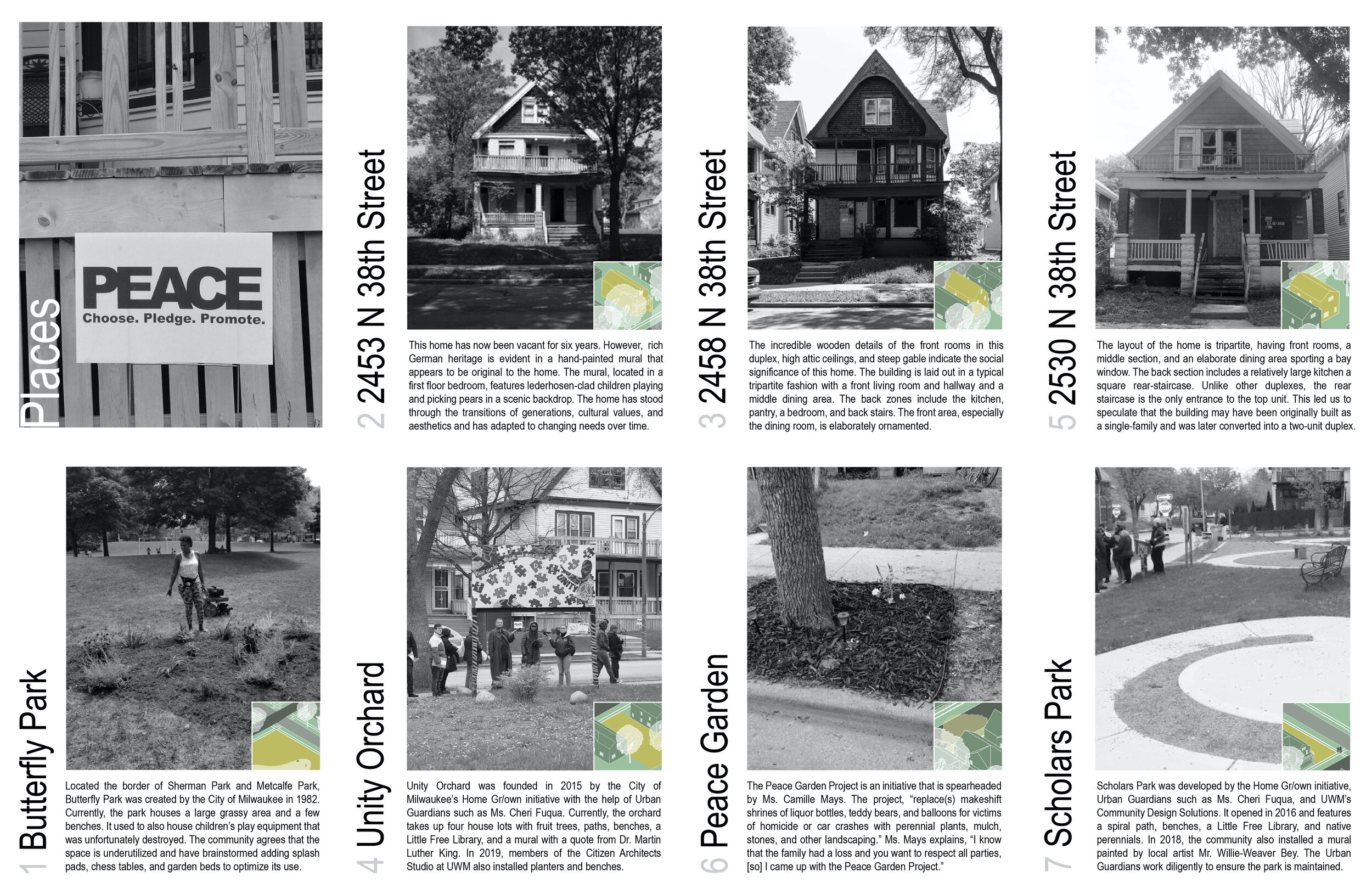

Geographers have referred to countermaps as documents that render visible solidarities at a local level; “local mapping, produced collaboratively, by local people and often incorporating alternative local knowledge” renders visible a powerful set of grassroots knowledge and resistance-practices otherwise invisible to the larger public.[8] Community-led walks revealed how our disciplinary benchmarks of significance and aesthetic value valorized property and stability of homeownership. Instead, we learned to focus on seeing place through the lens of displacement and movement—what Fred Moten calls the “shared presence in displacement.” For the African American residents of Northside, this shared history of displacement reaches back to enslavement but continues today in the form of evictions, incarceration, and homelessness. Narratives of displacement offered alternative stories of architectural heritage. That means a shared experience of temporarily occupying space didn’t always lead to stories of building types, ornamentation, styles, and craftsmanship. Instead we heard histories of meeting spaces, shared commons, memorials, and sites of labor and performance.[9] Bella Biwer who worked as a BLC Field School undergraduate research scholar for four years narrated the story of 38th Street in a zine (Figures 8 – 11).

Stories from the Northside

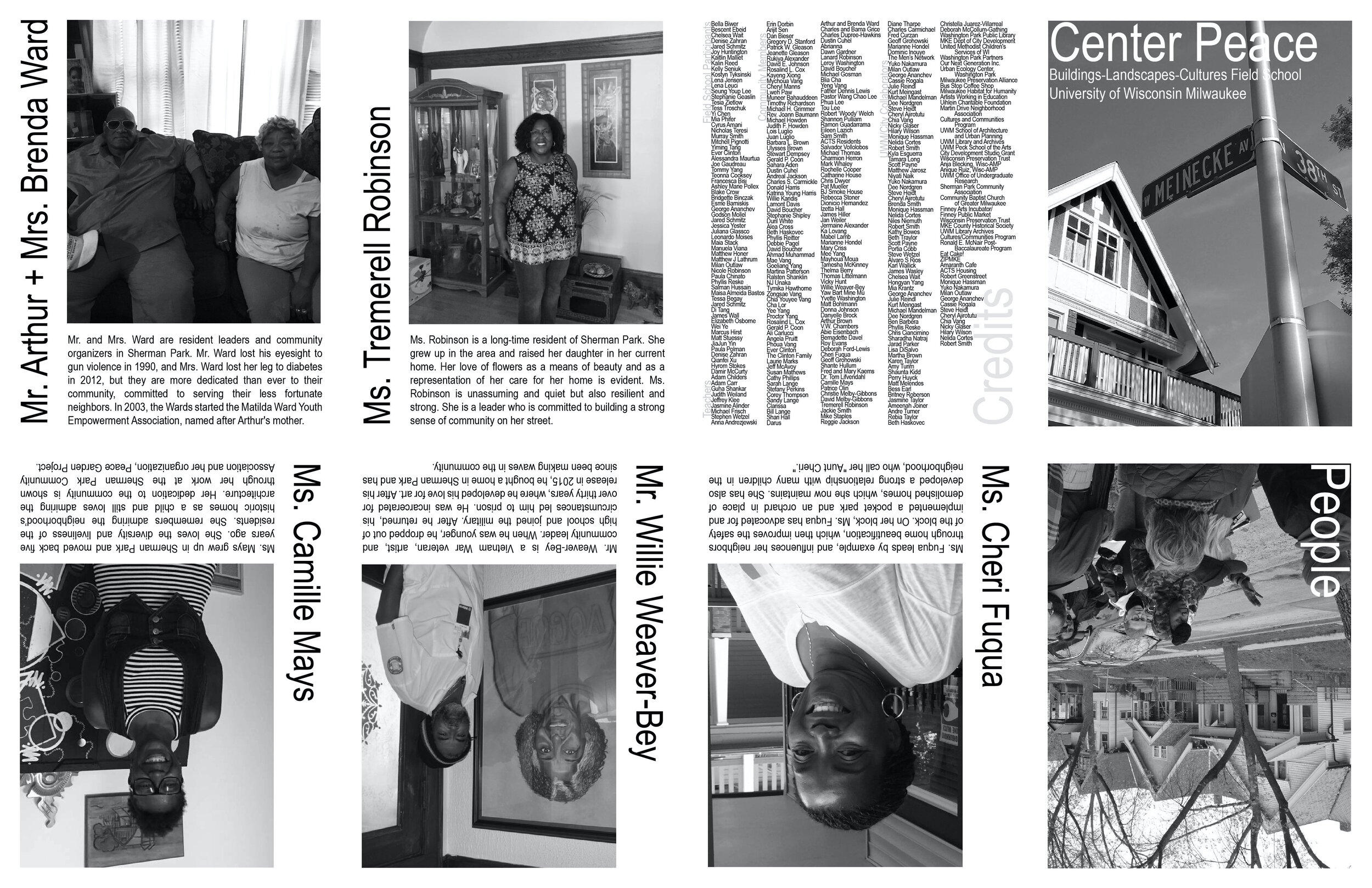

Izetta Hall’s story begins in Louisiana, where she grew up with her sharecropper mother and nine siblings. She came to Milwaukee when she was a teenager and moved between jobs and residences. Even when she rented, her home became a gathering point for many, including her foster families.

When Cheryl Manns described her Habitat for Humanity home as a “family home,” she was referring to a memory of a southern “homeplace” also described by bell hooks.

Tim Richardson described a history of porch sitting and couch surfing as spatial experiences that sustained homeless and transient bodies in the living rooms of friends and families.

Tremerell Robinson described her porch as a site of resistance. She has lived here since 1984. By the turn of the twenty-first century her neighbors retreated from the front porch into their private back yards to avoid being caught up in random street-side violence. The street became a no-person zone where white police officers controlled Black bodies with bigoted impudence. Robinson decided to take back her street by planting flowers and securing her porch.

Community matriarch, Cheri Fuqua corralled local youth to build an orchard and garden on vacant lots in her block because acts of caring encourages resilient relationships between neighbors. Stories such as these, reiterate political scientist Joan Tronto’s position that acts of caring offer, “a major alternative . . . to the neoliberal paradigm, both conceptually and historically.”

Camille Mays transforms roadside memorials for traffic and gun violence into pocket parks or “Peace Gardens.” Turning interstitial spaces into peace gardens are politically strategic actions because it produces what scholars such as Saskia Sassen describe as “a space where new forms of the social and the political can be made, rather than a space for enacting ritualized routines.”

NOTES

[1] See also, Anooradha Siddiqi and Andrew Herscher, Spatial Violence: Studies in Architecture (New York: Routledge, 2017).

[2] A New York Times video about the fallouts from the 2016 Milwaukee uprising quoted Milwaukee’s Mayor Tom Barrett repeating the familiar but faulty rationale that it is more important to halt property damage than to acknowledge a long history of injustice and the rage that such histories produce.

[3] Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), xiii.

[4] Amos Rapoport uses the concept of home range to describe the extents of setting and linked paths connecting that a human being traverses on a regular basis. Amos Rapoport, Human Aspects of Urban Form: Towards a Man-Environment Approach to Urban Form and Design (New York: Pergamon Press, 1977), 278. He uses the term “systems of activities and systems of settings” to describe a network of locations that constitute the world within which an individual operates. Home range in this ethological space model reflects the physical and social extent of this landscape. See, Amos Rapoport, “Systems of Activities and Systems of Settings,” in Domestic Architecture and the Use of Space, ed. S. Kent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990): 9-20.

[5] Writing about the Black vernacular, bell hooks argues that “Often, exploited or oppressed groups of people who are compelled by economic circumstance to share small living quarters with many others view the world right outside their housing structure as liminal space where they can stretch the limits of desire and the imagination.” bell hooks, Julie Eizenberg and Hank Koning, “House, 20 June 1994,” Assemblage 24, House Rules (August 1994), 24.

See also, bell hooks, “Black Vernacular: Architecture as Cultural Practice,” Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: The New Press, 1995), 145-151.

[6] bell hooks, “Homeplace : A Site of Resistance," Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (London: Turnaround, 1991).

[7] Joanne Rappaport, “Beyond Participant Observation: Collaborative Ethnography as Theoretical Innovation,” Collaborative Anthropologies 1 (2008), 4.

[8] See also, Chris Perkins, “Cultures of Map Use,” The Cartographic Journal 45: 2 (2008), 154. Les Roberts, Mapping Cultures: Place, Practice, Performance (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 7.

[9] In dance choreography such a move is called counterpoint: “two (or more) choreographic fragments with different use of space, time and/or body are executed together and make part of a choreographic unity.”