People’s Park, Autumn 2022, Part 1

Living is a gerund:

we do it in process.

People’s Park is a gerund:

a place of maybe but not yet

always coming

unless it’s gone.

On Wednesday, August 3rd, 2022, the University of California, Berkeley moved once again to reclaim People’s Park, with crews fencing and clearing; cutting down and chipping trees. The university’s goal is to build dormitories for eleven hundred students. Activists fought back, despite university promises to also build roughly a hundred units of housing with support services for unhoused and very-low-income people, and to commit sixty percent of the land for a “revitalized . . . green space that reinforces the site’s history” designed by acclaimed landscape architect (and Berkeley professor) Walter Hood. Hood and his team have long worked to design places that promote social justice. The problem is that People’s Park’s history isn’t over yet.

Figure 1. Panoramic view looking west, north, and east. People’s Park, Berkeley, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

The 2.8-acre open space was created in 1969, when activists occupied a muddy, stalled construction site owned by the university. They wanted to create a free, open, giving, and collective space; a changing, uncontrolled space; a space that would be free of government oversight and private ownership. In recent decades, People’s Park has become home to a shifting community of homeless people, and it is their dignity as well as the larger dreams for the park that activists wish to protect.

Figure 2. Disabled demolition equipment. People’s Park, Berkeley, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

The university’s attempt to reclaim the park was quickly met by its residents and other supporters, who tore down fencing, occupied trees, and disabled demolition equipment. Two days later, a restraining order halted work while a lawsuit by the People’s Park Committee and the People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group moved ahead. This January, following a preliminary ruling in late December that the university consider other sites for student housing, the college began removing construction equipment, but the final outcome remains uncertain.

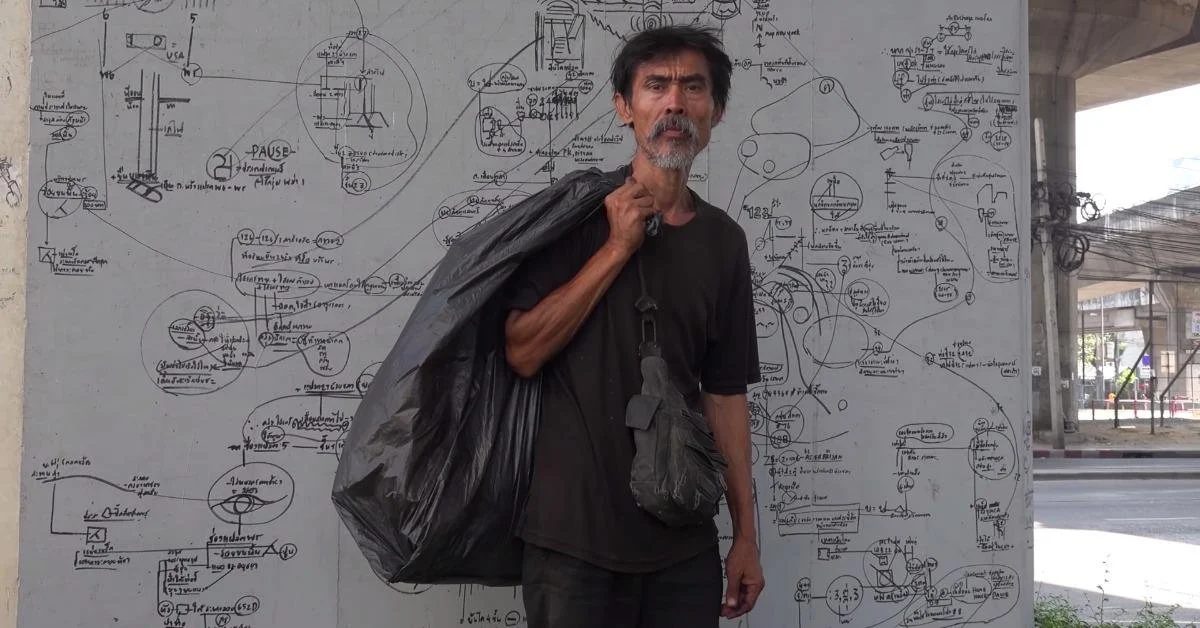

Over the course of last autumn, as unhoused people moved back into the partially destroyed park, I spent time there, watching, listening, and taking photographs, including those in this article.

Figure 3. Tents with university dormitories beyond. People’s Park, Berkeley, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

Shelter here comes in a variety of styles. Many residents live in store-bought tents, in different stages of readiness and disrepair, but there are also ingenious purpose-built structures of pre-insulated panels, held together with zip-ties and taped at the seams. A massive walled compound sits at the base of a lone towering redwood, with a newly rebuilt aerial platform. For days a screw-gun could be heard, while a head bobbed in and out of view in the treehouse. Some shelters are obviously in decline, and some people make do without one. Development, devastation, and redevelopment occurs on a vastly sped-up timeline.

Figure 4. Tents along Dwight Way. People’s Park, Berkeley, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

Homey furniture, carried from some curbside, finds a second life inside the shelters, or in the open air, forming outdoor living rooms, barbecue areas, and reading nooks. What is usually inside is mostly outside here; privacy is made public but for the homelike interiors of some of the shelters. One day I heard a woman shouting from inside a tent at a man who wanted her attention: “You can’t come in! You can’t come in!” Privacy in the park is hard won and hard kept.

I find this present state compelling and poignant. It’s also an ongoing expression of its founders’ concerns—for the dignity of labor, the rights of women, racial equality, peace, and liberation from the yoke of oppressive moral conservativism—and their questions: Can people work together in community without hierarchy? What would an open society look like if the welfare of all were the guiding principle? What are the costs of inhumanity?

“Can people work together in community without hierarchy? What would an open society look like if the welfare of all were the guiding principle? What are the costs of inhumanity?”

Figure 5. Commemorative poster of People’s Park construction, 1969. Creator unknown. Caffe Milano, Berkeley, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

The fight over this ground began in 1967, when, after years of planning, the university used eminent domain to buy out the owners of the block’s twenty-six houses. Its plan, then as now, was to build student housing, but the college left the lot empty when funding dried up. On April 20, 1969, activists moved in and began to build, with “colorful smiles, laughter, and lots of sweat,” a “cultural, political, freak out and rap center for the Western world.” For nearly four weeks work continued, without plan or program, with people choosing spontaneously, ad-hoc and together, what to build or plant, and where. Berkeley architecture professor Sim Van Der Ryn was a strong proponent, but he was also torn between his discipline’s need to plan and the imperative to do things collectively, without hierarchy, as the spirits moved people.

The days of creative togetherness did not last long. University, city, and state officials saw the park as a threat to civil order. An angry Gov. Ronald Reagan ordered police to “use whatever force is necessary” to stop the trespassers. This led to days of rioting and marches in which one man was killed, another blinded, and many wounded. At one point, police blocked exits from nearby Sproul Plaza on campus, where students were protesting in front of the chancellor’s office, and released tear gas. The park was soon fenced. As construction resumed in 1971, supporters mounted fresh protests, and in May 1972, a crowd tore down the fence and reoccupied the park. Over the following decades, as the university periodically attempted to reclaim its land, park defenders pushed back and homeless people took refuge amongst the trees. There were frequent arguments in the surrounding community over quality of life (for whom?) and the necessity (whose?) of the park.

Figure 6. Makeshift shelters with Bernard Maybeck’s Christian Science Church beyond People’s Park, Berkely, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

“Today, students mostly find the park unwelcoming and, with the shortage of housing in Berkeley more acute than ever, support the university’s redevelopment plan. People’s Park residents, however, remain committed to it.”

Today, students mostly find the park unwelcoming and, with the shortage of housing in Berkeley more acute than ever, support the university’s redevelopment plan. People’s Park residents, however, remain committed to it. They find it a relatively pleasant place to live, even in its current half-demolished state, providing both community and relative privacy. Neighbors, meanwhile, value it as urban open space, even if they’d prefer it served their middle-class needs.

Figure 7. Downed palm tree. People’s Park, Berkeley, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

As I observed People’s Park this fall, I wondered, are there lessons to be learned from it? The tents and makeshift dwellings among the downed trees and wood chips are as much statements of hope as of privation. The community food garden, maintained by volunteers, offers kindness and nourishment as an antidote to privatism. The park dwellers who take food are not abstract indictments of the United States’ failed safety net; they are individuals who deserve respect and admiration for their resourcefulness and ability to coexist. The structures built from scavenged materials are creative. The ways in which life grows among the wreckage recalls the experience of wartime, and the sacrifices made by a people in the service of a greater good.

Figure 8. Food distribution table, with redwood tree, compound, and tree platform beyond. People’s Park, Berkeley, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

But instead of collective sacrifice, redevelopment will exact private costs on individuals who can’t or won’t fit in with an unequal society that provides no room for them and that devalues care. The park is occupied by people who are not fully citizens of their city, because they cannot afford the privacy that enables a dignified public life. They have no roof to call their own, only precarious People’s Park, a place whose fate tenuously rests in the hands of others.

People’s Park is not the only place in Berkeley, much less the region or state, where people without homes are making shift to live, sometimes creating inspiring communities. And the shortage of affordable housing remains a national shame in the United States. But the park is, perhaps, the place where the contradictions of the larger housing and care crises are made most apparent, because of the ideological history of the place.

Figure 9. Disabled backhoe with improvised swing. People’s Park, Berkeley, Calif. Photograph by Helen Bronston, 2022.

Housing for twelve hundred and a landscaped memorial will neither solve Berkeley’s housing problems nor satisfy the university’s appetite for space. People’s Park, by contrast, and the issues it poses, can inspire new thinking, and bring new urgency to larger problems. Freedom, Liberty, Justice: we know that these political concepts are meaningless without actual freedom, true liberty, and a just society. And these cannot exist without love, care, and mutual commitment. In our imperfect state, we need the provocation offered by People’s Park far more than the University needs a new privatized and sanitized memorial to utopian dreams. Let us solve the larger problem of housing with dignity for all before we eliminate this one reminder, this last refuge, of the lofty goals of togetherness, mutual support, and freedom from oppression that brought People’s Park into being in 1969.