Immiscible Interventions: Graffiti and Mandala in the Modern Southeast Asian City

Sometime in the mid-2010s, unusual graffiti began to appear on the streets of Bangkok. Although graffiti has its own history in Thailand and is often used to express romantic, sexual, or political sentiments, this graffiti deployed a slightly different grammar (Figure 1). It was more visual, eclectic, and ambiguous than the usual text-oriented missives sprayed or scrawled in public spaces and vehicles. Often placed literally on the street or the few extant sidewalks, bus stops, walls, and foundation pillars of the Thai capital, these images were at once familiar and unusual. The basic form was that of a city map, and often familiar place names were annotated.

Figure 1. Graffiti by Pirachai Patanapornchai. Courtesy: Bangkok Art Biennale, Wikimedia Commons.

There were also strange departures from the known, visible built landscape, however: states of mind, like “boredom” or illustrations culled from technical manuals like “typical welding symbols” shared the same field as familiar landmarks like the Japanese department store Isetan or a place to get the “best haircut” as well as temporal references to calendar dates and historical events. Part intellectual diagram, part map, these psychogeographic compositions were later found to be the work of Pirachai Patanapornchai พีรชัย พัฒนพรชัย, or Pichai Ratanapornchai, or simply Samer เสมอ (“Always”). In various, contradictory interviews, Samer has declined the description of “artist” and spoken instead of the images he has created as representing narrative events, both real and imagined: the death of family members and a butterfly that transformed into a pigeon when he touched it, for example. However, it is difficult to disentangle Samer’s intentions and life story from the imaginative narratives he draws. Samer uses word associations related to rhymes and pictograms that often link with astrological stars and logos on buildings. The codes and symbols are entangled scribbles and numbers that reflect what he calls, “strategic places in Bangkok that relate to astrological stars of the city.” His drawings, he has said, seek to reveal these secrets to the public. He has even claimed that his drawings have forecast serious warnings on impending disasters, like the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 2).

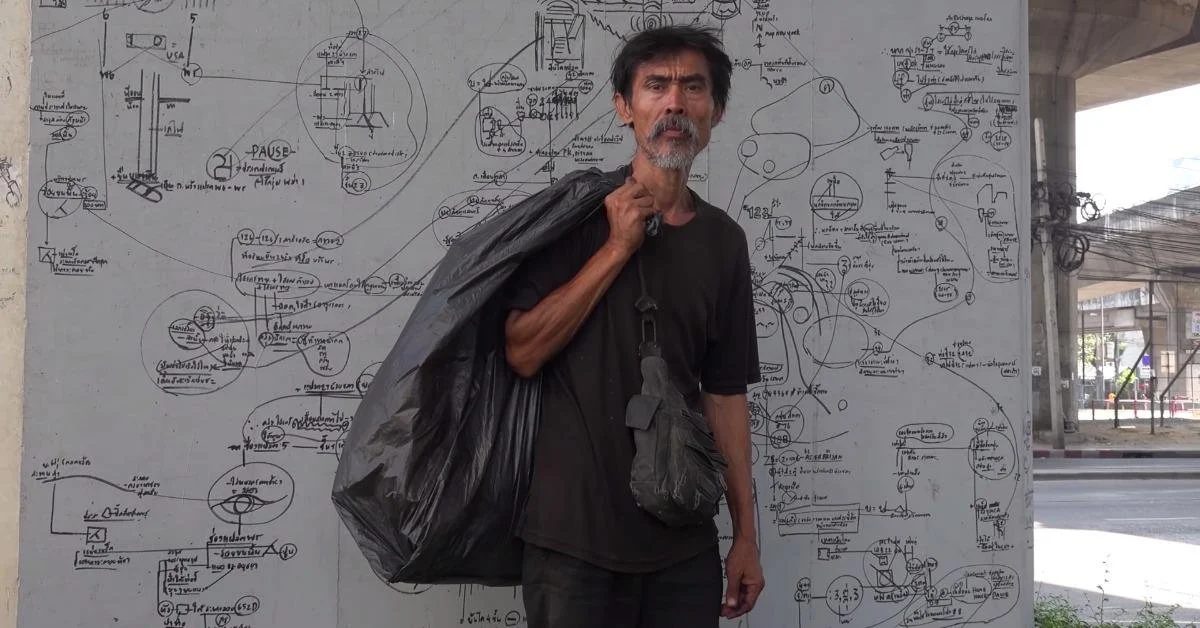

Figure 2. Pirachai Patanapornchai in front of one of his “mind maps.” Courtesy: Raphael Treza

The drawings begin by following the contours of the city’s topography, a crack in the sidewalk, the seam of the street, a glitch in the infrastructure, suggesting, like much graffiti does, the malleability of the city’s physical infrastructure and public spaces (Figures 3 and 4).[1] Rather than embellish another layer of the city’s palimpsest, they instead delaminate the city’s history, excavating the logics of earlier cosmologies that have since been disguised by the rational mask of concrete, asphalt, glass, and air conditioning. The city has wrestled with these multiple identities since the nineteenth century, when the monarchy attempted to impose a modern gridiron on a city that owed its founding morphology to a concentric mandala. In recent years, the city’s new democratically elected governor Chadchart Sittipunt has initiated several creative urban reforms that seek to not only address chronic infrastructural problems, homelessness, and the deterioration of community living standards caused by decades of corporate-driven private development and haphazard planning policies, but to put the city in consonance with ever-changing environmental conditions exacerbated by climate collapse, including increased seasonal flooding and subsidence.

Figure 3. Graffiti by Pirachai Patanapornchai on the sidewalks of Bangkok. Source: Just Sayori, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4. Pirachai Patanpornchai creating one of his “mind maps,” Bangkok. Courtesy: Raphael Treza.

The intersection of cosmos and terrain is perhaps most acutely visible to those deemed peripheral to urban capitalist society, like Samer. Samer’s work, in turn, suggests that understanding the premodern, precolonial truth claims and spatial knowledge production that haunt the modern city is part of the struggle to recover an urban historicity beyond empire- and nation-centered discourses. His work draws on an experience of anachronistic temporality that has been historically accommodated by tools used in premodern Southeast Asian worldmaking such as the yantr ยันตร or mandala. Samer’s work offers a useful heuristic for understanding the “immiscible times” of the modern Southeast Asian city. I use the phrase, following cinema scholar Bliss Cua Lim, to point to urban moments that never dissolve into the homogeneous codes of modern time consciousness and continue to haunt the built environment of cities like Bangkok. In accentuating the anachronistic features of the urban landscape, Samer’s work opens up an aperture for overcoming or, at least recognizing the teleologies of linear causal histories that privilege the nation-state as the denouement of both decolonization and the imperial project.[2] By reminding us of the uses of anachronism, Samer’s interventions into the city’s built fabric offer another way to understand the past, as something that is always present.

Samer’s work draws on the vocabulary of the yantr or mandala that was an important tool in Indic town planning and worldmaking in Southeast Asia from roughly the tenth through the eighteenth centuries. The yantr is a spatio-temporal diagram, used to model the city on the order of the cosmos. It draws on multiple forms of autochthonous and Indic place-making knowledge, including astrology, mathematics, religion, statecraft, agriculture, and warfare. Precolonial approaches to planning Southeast Asian cities were not only concerned with the terrestrial logistics of the urban but sought to actively place the realm of human life within a larger cosmological framework that could accommodate multiple temporalities and subjective experiences (Figure 5). Acknowledging not only the persistence of this framework but the ways it has been transformed by the descendants of earlier populations challenges the imperial valuations of architecture and urbanism that form the foundation of the discipline of architectural history.

Figure 5. Naganam mandala from the 1825 recension of the Tamra phichai Songkhram, republished by the Department of Fine Arts in 1969. Redrawn by Alexander Kuhn in Bangkok Utopia.

The mandala that was key to the foundational “plan” of Bangkok, the naganam, shares the same grammar as Samer’s graffiti. The naganam provided the basic morphology of the capital at its founding in the eighteenth century and came from a manual of divination and warcraft known as the Tamra phichai songkhram or the Manual for Victory in War. Related to the Indic śastras, the Tamra phichai songkhram shared similarities with the Arthaśastra, the Sanskrit treatise on statecraft and military strategy, such as detailed battle formations and strategies for deceiving the enemy. Most of the Tamra phichai songkhram consists of illustrated omens and mandalas to predict the outcome of battle. The omens are read from astrological calculations based on constellations or observations of nature, such as the shapes of clouds and appearance of the sun and moon, but also include strategic formations whose forms were derived from chthonic chimeras of the Himmaphan forest, the mythical woodlands that surround the axis mundi of the Indic cosmos, Mount Meru. The Tamra phichai songkhram thus integrated a reading of the celestial bodies of the cosmos with terrestrial concerns of strategy and fortification through a vocabulary of symbolic geometry (Figure 6).

“The drawings... delaminate the city’s history, excavating the logics of earlier cosmologies that have since been disguised by the rational mask of concrete, asphalt, glass, and air conditioning.”

Figure 6. Illustration from a nineteenth-century leporello manuscript of the Tamra phichai Songkhram, British Library Or. 15760. Copyright: The British Library Board.

The naganam was named after the naga, a chimeric water serpent. It was considered the most appropriate for the new geography of the city because it indicated the strategic placement of troops along flowing waterways. (Cities in this part of Southeast Asia were historically built along rivers, rather than coasts). The naganam had both temporal and spatial aspects: it predicted the scheduling of troops based on auspicious signs and determined that the sixth lunar month was the last month that the naga’s head would be in the west. Therefore, any auspicious activity in the future would have to be done in the eastern direction. Sunday, it was also noted, was the day of auspicious peace and victory in defense. So, on Sunday, 21 April 1782, a new lak muang or city pillar was installed with some haste on the east bank of the Chaophraya river. The first king of the new dynasty that ruled from Bangkok, Phuttayotfa or Rama I, chose a site for the pillar on an axis with Wat Bang Wa Yai (today Wat Rakhang Khositaram) on the western bank of the river, then the home of the Somdet Phra Sangharat, or the supreme patriarch of Thai Buddhism. The city pillar thus marked the head of the naga, while the home of the supreme patriarch was its tail, and the axis between it and the city pillar linked the two side of the river through the body of the naga (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Map of Bangkok showing the axis between the city pillar (lak muang) and the home of the Supreme Patriarch of Thai Buddhism (Phra Sangharat) at Wat Rakhang Kositaram (formerly, Wat Bang Wa Yai). (https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1xqYFUqrDeIORfxRhndgIZQH_1bL6KI8&usp=sharing)

Given the turmoil of the period in which Bangkok was founded, the naganam mandala was not just a strategic plan for the defense of the new capital, but a model of certainty for the future of the new dynasty, offering up a diagrammatic parallel between what historian Paul Wheatley has called “the regular and mathematically expressible regimes of the heavens and the biologically determined rhythms of life on earth.” [3] The mandala has a long history as an instrument for meditation, insight, and ritually demarcating consecrated space in Theravada Southeast Asian polities. It provided a spatial template whereby the moral precepts of Theravada Buddhism and Brahmanism could be replicated in the mundane world of the political capital. It also served as a metaphor for the political organization of Southeast Asian polities. The “mandala polity” is a modern conceptualization of Southeast Asia before the era of high colonialism in the nineteenth century: an arena full of petty, urban-based kingdoms rather than a single centralized state. It describes the network of loyalties between ruler and ruled and among rulers, all of whom aspired to be the highest lord of the area over which they claimed sovereignty. The Thai term monthon, derived from the Pali mandala, refers to an administrative region and a circle. It reflects the multiple meanings embedded within the mandala: more than a symbol, it sought to structure the terrain of the material world after an abstract rhetorical image of celestial space. In theory, the built environment of human and divine habitation in premodern South and Southeast Asian cities was ordered on the geometrical pattern of a place-making mandala, the vastumandala or vastuyantra. This mandala was generated by an axis mundi, an existentially centered point of transition between cosmic planes. In lived space, the axis mundi was sheltered by a sacred enclave or temple that was oriented to the cardinal directions, assimilating the kingdom to the cosmic order and constructing a sanctified living space within profane space. The ordered cosmos represented in the temple was then amplified axially across the city (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Detail of the phra merumat or cremation pyre of King Rama IX, showing various chimera on the slopes of Mount Meru. Photograph by Lawrence Chua.

Southeast Asian cities, then, were cosmic centers. But the center in this context should be appreciated as both a horizontal and vertical center or the pivot of intersecting cosmic planes. For example, the Indic cosmos described in the various recensions of the Traiphum or Cosmology of the Three Worlds was inhabited not only by humans but by other sentient beings, gods, and spirits, so the urban center of premodern cities was never limited to human habitation: just as the original orientation of Bangkok was modelled on the body of the naga, images of the naga and other chimera proliferate in its architecture. A chimera is an organism whose cells come from two or more different organisms; it is a mixture of genetically different materials. These images are thought to predate the early period of Sanskrit influence in the region and persist through until today, but they also speak to the ways diverse waves of cultural influence have come to be incorporated into Southeast Asian architecture (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Garuda on the cornice of the General Post Office (Miw Jitrasen Aphaiwong). Photograph by Lawrence Chua.

Several historians have noted the polysemous nature of the term “naga,” which in Old and Middle Indian texts can refer to a mythical serpent, an elephant, or a tree. Perhaps because of this ability to stand in for different but related things, the naga provides the foundation for many metaphors in the region. It serves as part of the foundation myth of several Southeast Asian communities. For example, in his thirteenth-century account of the customs of Angkor, Zhou Daguan noted that the king had sexual relations with a nine-headed naga that could transform itself into the form of a woman in one of the towers of his palace.[4] The naga has also served as a metaphor for the Mekong River and is held responsible for the river’s ebbs and flows. It is kin to the Indic Śesa naga or Śesa-ananta or Nagaraja, the endless serpent of the cosmos who served as a cushion for Vishnu and gave birth to Brahma. When the Śesa-naga uncoils, time moves forward and creation takes place; when it coils back, the universe ceases to exist. In architecture, the naga is sometimes identified with the rainbow and depicted as rainbow-shaped lintels. The rainbow symbolized both the bridge from earth to the upper realms and the giant water serpent raising its head from the ocean to drink water. In Theravada Buddhist temples, naga-shaped stairs symbolize the three ladders linking heaven to earth. The naga is also critical for housebuilding rituals in mainland Southeast Asia. The position of the Śesa-naga, must be considered before digging the pits to erect posts. The Śesa-naga is the great serpent that supports the three worlds of the cosmos (the world of the senses, the world of form, and the world of formlessness) and moves its head, following the sun, a degree every day. In the 4th, 5th, and 6th months, the naga’s head faces west and his tail is to the east, his belly is to the south and his back to the north. As long as one digs towards the naga’s belly, the portents will be favorable for building. The naga’s deployment—and its polysemous history—in diverse contexts suggest that the naga is a creature, a symbol, and a metaphor for transformation that has been a part of Southeast Asia’s landscape throughout its early indigenous civilizations, during its Sanskritization, during the introduction of Brahmanism, Vajrayana and Theravada Buddhism, and Islam, and during the nineteenth century period of high colonialism. It has changed, just as populations in Southeast Asia have changed, engaging local and “foreign” influences to produce distinctive urban-based cultures. These influences exist as fragments that are now internal to the genetic imaginaries of the naga. The relationship between naga and human can be understood as one that was made possible by the close proximity in which humans interacted with not only other sentient beings but with ghosts and divinities. In mainland Southeast Asia, the premodern taxonomical distinctions between human and non-human, civilized and uncivilized, existed not as immutable binaries but as stages in transformation, and the ability to move between different planes was possible through the cultivation of correct behaviors (Figure 10).

“How might we understand the ability to transform oneself through the city as not limited to those with capital or those at the top of a feudal social hierarchy but as an ability made available to all who adopt ethical modes of living, in consonance with the movements of the earth and its waterways?”

Figure 10. A balustrade depicting a makara disgorging a naga at Wat That Phun, Vientiane, Laos. The makara and naga are chimeric creatures that inhabit the Himmaphan forest on the slopes of Mount Meru, the center of the Indic cosmos. Source: Chaoborus, Wikimedia Commons

We return then to a familiar modern image of the city as a place of transformation, a site that offered, to borrow Marx and Engel’s trenchant phrase, an opportunity to escape the idiocy of rural life, but in the case of Southeast Asia was also an occasion to pursue other temporalities.[5] In the nineteenth century, this meant an escape from the slow, seasonal rhythms of cosmological time and agricultural production, exactly the rhythms that premodern city and town planning sought to accommodate for the modern, industrialized clock. Deepening our understanding of premodern urbanization in Southeast Asia, however, opens up an aperture into understanding transformation in a way that is not shaped by the ontologies of the capitalist marketplace. In fact, the Traiphum and other texts that informed premodern urban planning and monastic architecture in Southeast Asia can also be understood as a diagram of moral practice, with each level of the heavens indicating a stage in the cultivation of insight. How might we understand the ability to transform oneself through the city as not limited to those with capital or those at the top of a feudal social hierarchy but as an ability made available to all who adopt ethical modes of living, in consonance with the movements of the earth and its waterways?

Samer’s interventions on the streets of Bangkok underscore the value of recovering potential modes of being, particularly collective modes of being, from the preimperial past as an important part of the deimperialization of knowledge about architecture, cities, and urban community. Such local expressions of knowledge about space- and place-making are often poorly represented in historical narratives about modernity as archaic or primitive versions of art, architecture, and urban planning. They, however, continue to challenge both inhabitants and scholars of the modern Southeast Asian city to better understand the ways human settlements exist not only within more expansive spaces but within more complex temporalities that seek to integrate not only the “classical,” the “medieval,” and the “modern” but also cosmological and biological time. Samer’s immiscible interventions allow us to understand the expansive and continuous histories of place-making, of which we might consider architecture a part.

Notes

[1] Swati Chattopadhyay, Unlearning the City: Infrastructure in a New Optical Field (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 162.

[2] Prasenjit Duara, Rescuing History from the Nation-State (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 6, 16.

[3] Paul Wheatley, “The Suspended Pelt: Reflections on a Discarded Model of Spatial Structure,” in Geographic Humanism, Analysis and Social Action: Proceedings of Symposia Celebrating a Half Century of Geography and Michigan. Edited by Donald Deskins, Jr., Goerge Kish, John Nystuen, and Gunnar Olson (Ann Arbor: University of Michicgan, 1977), 52-54.

[4] Zhou Daguan, Notes on the Customs of Cambodia (Bangkok: Social Science Press, 1967), 22.

[5] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1977), 38.