Stories from the Flatlands

Once, when I was new at my job, a reputed architectural historian took me aside to give me some well-meant advice. Architectural historiography, he said, was all about evidence, objectivity, and meticulousness. Fieldwork could have no place for emotions and tropes—he particularly detested the word trope used in literary and cultural studies circles. We measure buildings carefully and precisely with scientific objectivity and fieldwork involved touching, examining, documenting, and interpreting artifacts. “Materiality matters,” he muttered under his breath.

That sincere advisory failed to help me uncover the rich African American history of Milwaukee’s Northside. If there were any physical patterns to be discovered here, they were material evidences of disinvestment, declension, and demolition. If you take a drive along Milwaukee’s Vliet Street you will see rows of empty lots and unkempt lawns. Your car will bump and bounce on the blacktop scarred with potholes that never seem to be repaired. These sensory experiences are important because they send a message that written and spoken words fail to expose and building analyses tend to ignore. The significant materiality of buildings that many architectural historians love to document may be conspicuously absent in these spaces, but our embodied experience of derelict landscapes lends itself as apt objects of critical analysis.

Figure 1. Image of a vacant lot and boarded up building in Milwaukee’s Northside. © Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School, 2017.

The experience of driving on Vliet Street exposes terrains that seem flattened and depleted of value. I call them flatlands because this flatness is purposeful,—a political condition that erases the inequity and hides the processes that produce this state of being. Flatlands don’t appear overnight. Instead they are carefully planned, purposefully dismantled, and painstakingly reproduced over time. The stories of removal and demolition are complex, layered, and often carefully shrouded by powerful forces that stand to gain from these erasures. Correlated with media depictions of poverty, disinvestment, and crime, flatlands have become a shorthand for social malaise in Milwaukee. In a hyper-segregated city such as Milwaukee, where Black and Brown neighborhoods are separated from white ones, flatlands represent differential social power and boundaries, often racialized.

“Flatlands are not really flat. But in order to discover a world hidden behind this seemingly lifeless optical field we had to employ a different fieldwork strategy. ”

Scholars such as Saskia Sassen, Ignasi de Solà-Morales, and David Harvey see flatlands as material conditions of contemporary capitalism.[1] In order to interrogate flatlands as a historic condition, in addition to archival and material analysis, we need to account for the experiential, the ephemeral, and the affective as objects of analysis.[2]

Figure 2. Foundation Park, W. McKinley Avenue and N. 37th Street. © Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School, 2015.

At first sight Foundation Park is not a typical flatland because it is a neighborhood park (figures 2 and 3). The park is located at a dead end next to an old railroad right-of-way abutting the historic 30th Street Industrial corridor. Harley Davidson Motorcycle Company’s corporate campus and Advanced Waste Systems, an industrial chemical treatment plant is located south of this park. Large truck trailers containing chemical wastes use this street in front of the park to get to their destination—the only sanctioned route through this residential neighborhood. In 2008, the Harley Davidson Motor Company funded this park on city-owned vacant land where a group of duplex homes and a saloon once stood.

In late 2016, news spread that the play equipment in the park was torched in a night of brutal arson. Residents began sharing stories of teenagers hanging out. Fears, that this corner space had become a drug corner, came to fore at neighborhood safety meetings sponsored by Harley Davidson Motorcycle Company and the Milwaukee Police Department. The location of the park became the focus of much discussion. In 2017, during safety meetings officials and some terrified residents argued that flattening the properties around this park could make this area safe because it will help police to survey this corner from their patrol cars. Specifically, their plans included suggestions to demolish two buildings that remained on the western edge of the park.

Figure 3. Community engagement and conversations around place and history. Our collaborative research with this community included an engaged design studio. © Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School, 2016.

During a neighborhood meeting at the Harley Davidson campus, in fall 2016, police referred to this process as a way to create defensible space. The term originated in the 1970s with the works of Oscar Newman and C. Ray Jeffrey.[3] Newman’s original intent was akin to community policing carried out by “eyes on the street,” but the term has been highjacked to refer to policing and militarized surveillance in contemporary parlance. Building demolition is part of a longer, more complicated, history of flattening terrain in low-income neighborhoods. Citing Wilson and Kellings’ now popular broken windows theory, city inspectors identify untended empty lots or boarded up buildings as potential sites of crime. However, this theory is problematic and has been heavily critiqued for its over-dependence on visual analysis in determining blight. Although the process may seem rational it is actually based on culturally produced affective reaction and an aesthetic judgment on how a building looks from the outside.

No decisions were taken at the meeting, but a careful study of the city records during that period shows that there were considerable activities around this property. Multiple occupancy permit requests were made between 2014 and 2016 and the Department of City Development seems to have made some code enforcement inspections (figure 4).

Figure 4. Record of sales of 1304 North 37th Place, adjacent to Foundation Park. Property Assessment Data, City of Milwaukee.

1304 North 37th Place, built in 1912, sat as an abandoned boarded up, two-unit residential property. In 2015, the property appeared in city records as owned by Deonate Anderson. The City took possession of the property by January 2016. The porch roof had sagged and partially collapsed, and windows were broken. Next to this home was a duplex owned by Thomas Davis, delinquent on city taxes, but occupied. We realized that broken windows didn’t mean broken homes and broken communities. We met Nate, who lived there with his siblings and parents in this house. Nate and his friends on his street often played in Foundation Park (figure 5).

Figure 5. Nate and his friends and local residents converge in Foundation Park during a community engagement event held by the Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School. © Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School. 2016.

But the process of flattening this site had an even longer and more hidden history. The duplexes were originally part of a compound of buildings on this block. This block itself was a remnant from a twentieth-century industrial era working-class neighborhood that grew around the paternal shadows of factories. That landscape changed drastically in the last few decades as the old industries disappeared or restructured with a new workforce. Many similar buildings located along McKinley Avenue and Vliet Street were torn down and converted into parking lots. A pattern of destruction and demolition closely followed the ways by which the industrial landscape changed in the last four decades.

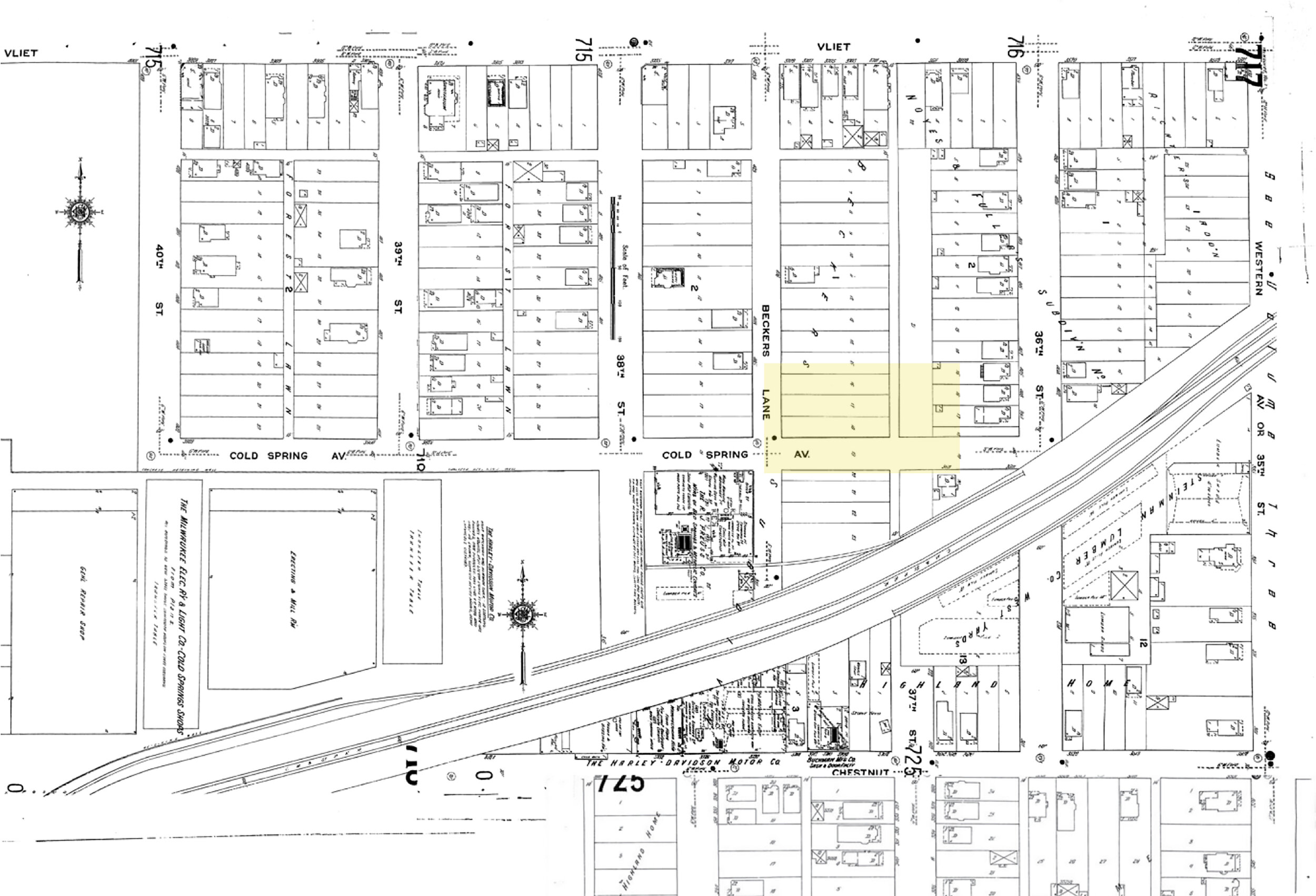

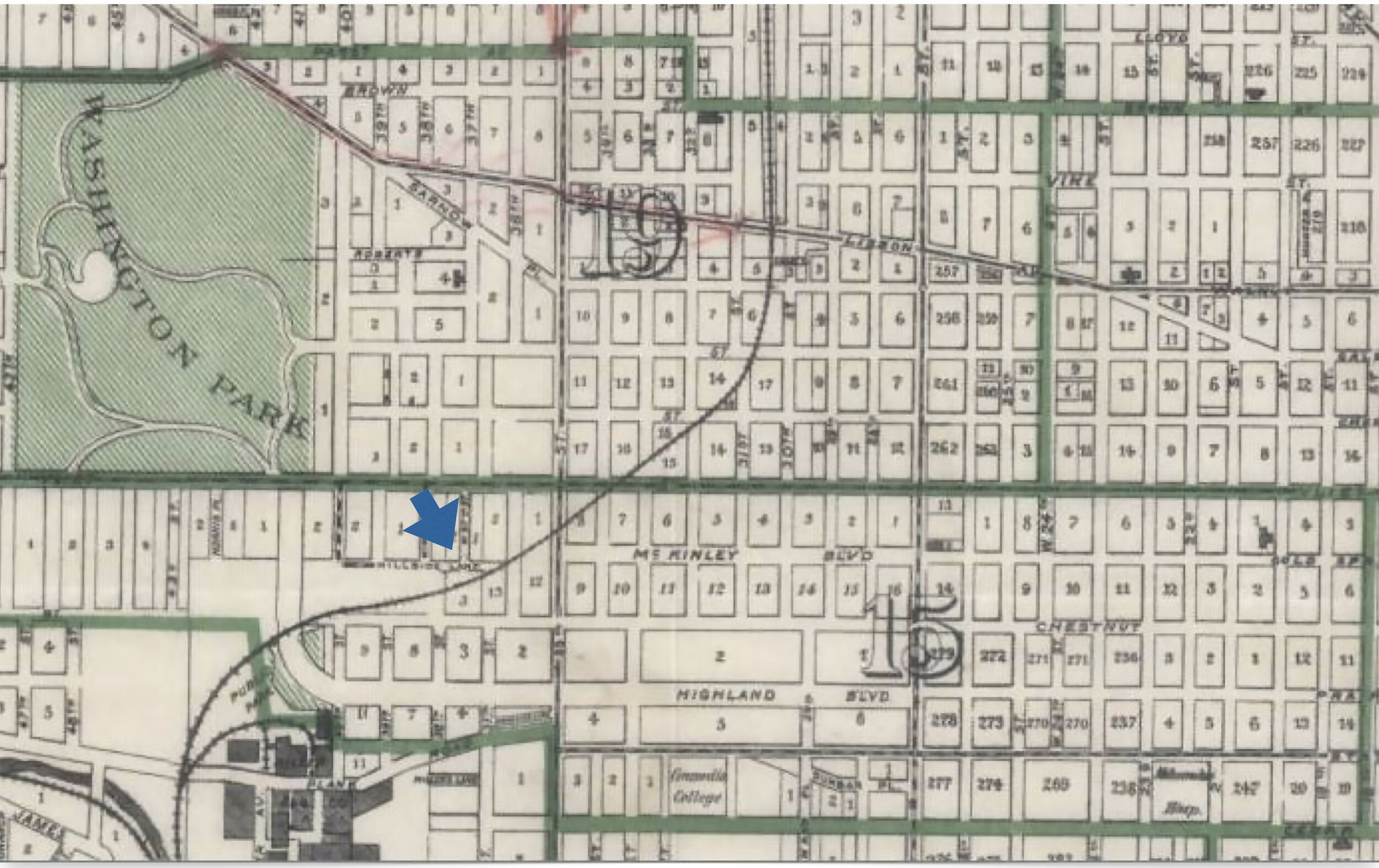

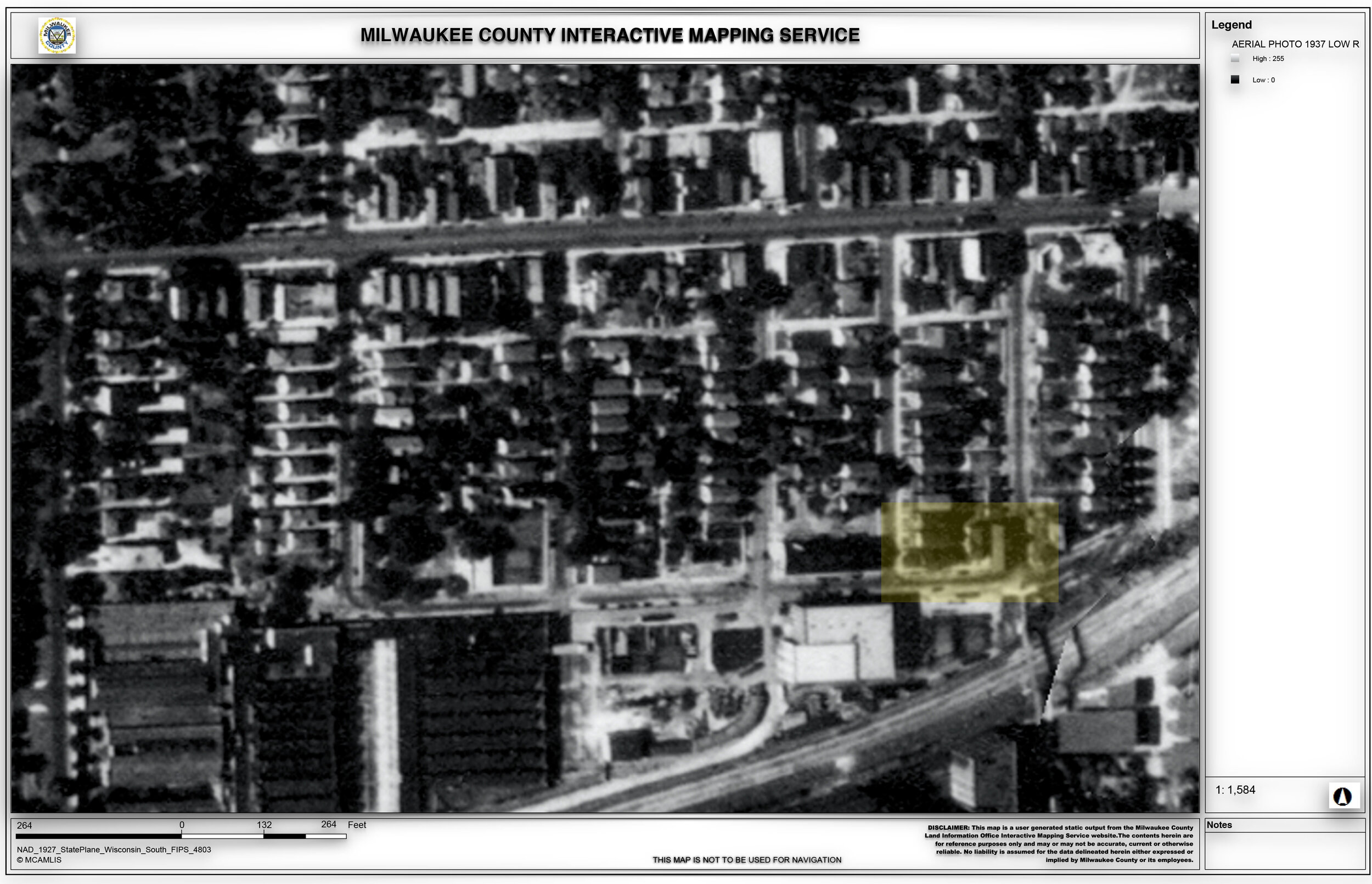

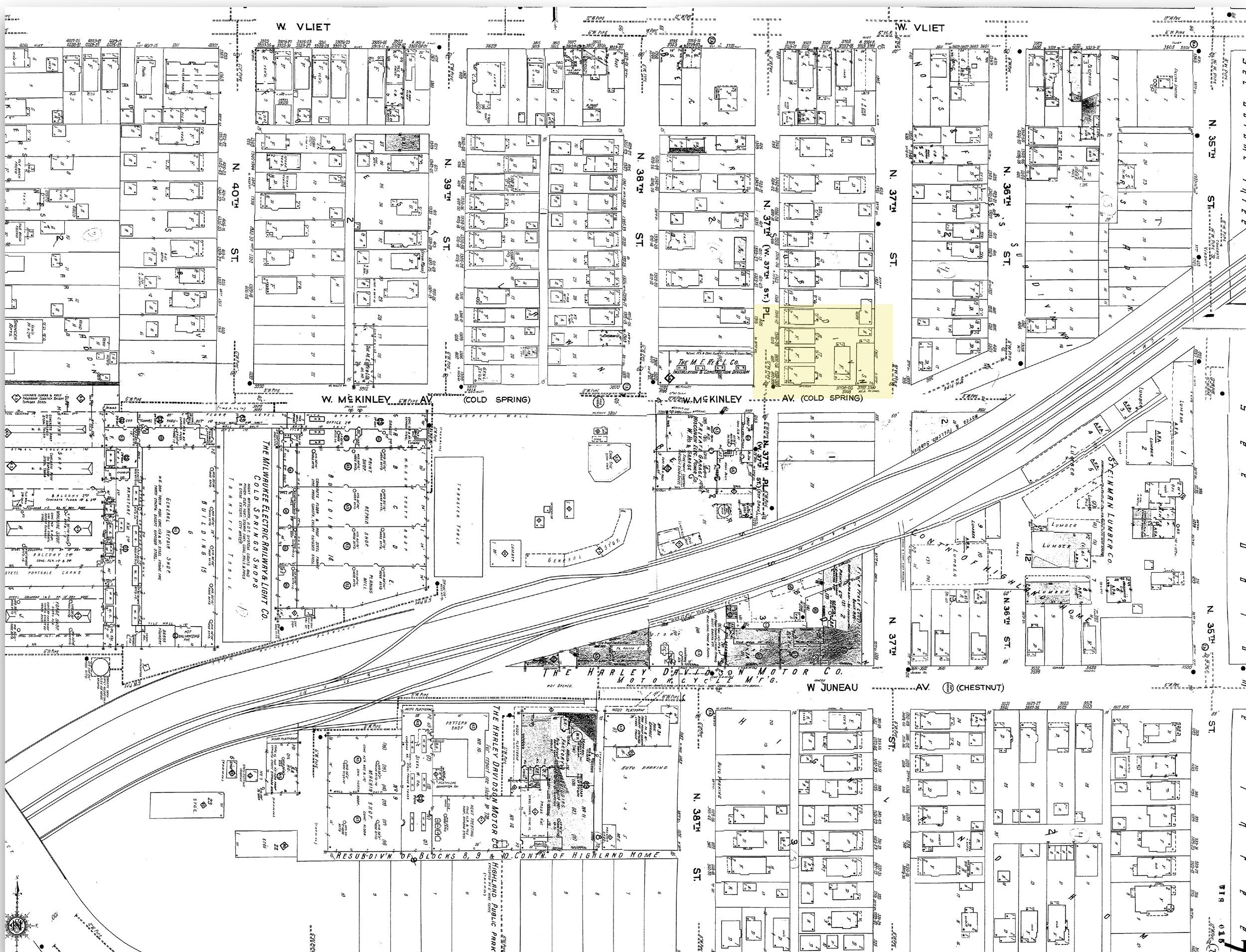

The earliest Sanborn Map from 1910 shows this neighborhood as sparsely populated. The corner of 37th Street and McKinley Drive was part of the Noyes and Fuller’s subdivision adjacent to industrial properties such as the R. J. Preuss Company that made bedsprings and metallic couches, Cold Spring Shops owned by the Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company, lumber yards, and a fledgling Harley Davidson factory. By 1916, the area turned substantially denser as a large number of residential buildings appeared in the subdivision, now sold off to speculative developers. Multiple streetcar lines served nearby Vliet Street, and the factory jobs and transit lines drew newcomers. By 1937, aerial survey maps show that flats, duplexes and boarding houses filled the neighborhood. During this period, the Harley Davidson factory grew substantially from its 1910 footprint. Between 1920 and 1950, this street became home to first generation children of immigrants—mostly ethnic German families—holding at best a high school diploma. The 1930 manuscript census lists many employed in Harley Davidson and nearby industries as boarders, tenants, and owners of these flats.

The neighborhood was thriving. The 1951 Sanborn Map shows 4 apartment buildings, a saloon and an automobile garage on the site of today’s Foundation Park. One could imagine the workers, many of them men, crossing the pedestrian bridge over the tracks on their way back from the Harley factory. As they crossed over the tracks into the residential area and before they went home, they encountered, perhaps even spent a while in the saloon located on the site of today’s Foundation Park.

“After the 80s, deindustrialization, job loss, and incarceration destroyed this neighborhood, frayed stable class bonds, and irrevocably changed the character of this neighborhood and its surroundings.”

After World War II, this tightly knit, walkable neighborhood began to see major changes that would completely transform this area. Streetcars disappeared, buses and automobiles took over, garages and parking lots appeared. Suburban flight, urban renewal, and urban policies slowly turned the economy and demographics of this neighborhood and the white working class families were replaced by African Americans.[4] By the 1950s the Preuss bedsprings and metal company was replaced by Harley Davidson’s garages and parking lots. By the late fifties, a number of economically stable and upwardly mobile working-class black homeowners settled in nearby areas. Many white homeowners moved out of this neighborhood and fled to newer suburban developments. This exodus was facilitated by federal housing loans and crooked real estate practices such as block busting. After the 80s, deindustrialization, job loss, and incarceration destroyed this neighborhood, frayed stable class bonds, and irrevocably changed the character of this neighborhood and its surroundings. Almost all local industrial jobs had moved away leaving only Harley Davidson in this spot.

In April and May 1993, the city demolished the tavern and rooming houses to create the current park lot. Between 1976 and 1995 many flats and saloon buildings were demolished, and the growing row of parking lots created a boundary zone separating the factory campus from the neighborhood. By 2007 the two lonely houses were the last standing structures on this site (figure 20).

Figure 20. Two duplex homes. 1304 N. 37th Place (left) and 1300 N. 37th Place (right). © Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School. 2016.

This story of slow-flattening coincides with major changes and corporate restructuring of the Harley Davidson company. By 2010, the Harley Davidson campus became home to the company’s corporate headquarters and its industrial production plant moved away. Harley’s new white-collared employees drove from the suburbs. The visitors to this campus were no longer workers walking to their shifts from the boarding houses. Instead they were corporate visitors, business investors and international collaborators. The economically disinvested, majority black neighborhood was neither an organic part of this industry nor a neighborhood that aligned with the changing priorities of the institution.

By 2015 Harley had teamed up with local healthcare, university, casino, and beer industries to create a development partnership that focused on making this neighborhood a “better place to live work and play,” and “to revitalize and sustain the Near West Side as a thriving business and residential corridor, through collaborative efforts to promote commercial corridor development, improved housing, unified neighborhood identity and branding, and greater safety for residents and businesses.” They began Promoting Assets and Reducing Crime (PARC) partnership, a three-year, $1.5+ million initiative that leveraged law enforcement and economic resources to improve neighborhood blight largely by buying up adjacent properties, addressing negative-impact properties, enhancing police presence and surveillance, while working with business and other stakeholders to change the perception of this neighborhood and attract economic development opportunities.” Community residents were worried about displacement and gentrification and as a result, they too became very sensitive to incidents related to safety and criminality.

The invisible hand of Harley Davidson Corporation continued to consolidate a buffer zone between the factory and its mostly black and poor neighbors. A 2019 aerial map shows how the process of flattening continued on the eastern edge of Harley’s campus where an old Kohl’s grocery store purchased by Harley was demolished. The property turned into a parking lot.

Flatlands are not really flat. But in order to discover a world hidden behind this seemingly lifeless optical field we had to employ a different fieldwork strategy.

We conducted primary fieldwork during summer, as part of the Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School project. Engagement with community members stretched into multiple semesters in the form of community-led walks, workshops, art events, and construction projects where students and scholars worked alongside community residents to build gardens, and street furniture. These events gathered citizens and scholars around civic conversations and collective actions in community-identified sites of heritage.

Field school scholar Hyrom Stokes mapped the sounds of a socially vibrant, albeit ephemeral world on Vliet Street at night. To him, a visual analysis of this neighborhood during the day provided an incomplete story of the world that lay hidden here. In fact, his research demonstrates that what we saw was deeply deceptive. The image of broken buildings, parking lots, and lack of maintenance was an artifice that hid the vibrant life on these street. Hyrom lived in this neighborhood and he knew that the sounds and smells of this neighborhood changed after the sun went down.[5] People returned from work, residents on double shifts left their home, children played on the streets, young adults led afterhours basketball games. Many played “kick the can.” Sex workers were out looking for customers and on a good evening, customers zipped by. Hyrom collected the sounds of this area after dark as a form of data that allows us to access a world that is otherwise hidden from our visual field. The predictable sound of goods trains along the industrial corridor, often carrying hazardous chemicals remained a lasting memory of an era long gone, but a constant reminder of new forms of environmental injustice and apathy that affected lives in this area.

Stokes’s fieldwork shows that while opti-centric daytime analysis of flatlands suggests a space bereft of value, nighttime soundscapes disclose the existence of empty lots temporarily transformed into basketball courts, sidewalks turned into playgrounds, and stoops into social spaces. These alternative stories challenge the rhetoric of flatlands as an empty slate, a tabula rasa, that business interests and city planners rush in to redevelop.

“while opti-centric daytime analysis of flatlands suggests a space bereft of value, nighttime soundscapes disclose the existence of empty lots temporarily transformed ”

Sounds and smells are ephemeral and protean senses. They move and change over time. Hyrom’s evening soundscape shows us the vibrant world that remain invisible to the architectural scholar who construes visible materiality as the essence of rigorous fieldwork. The soundscapes also show us that the correlation between flatlands and deviancy is carefully constructed. Another world exists in the neighborhood around Foundation Park, albeit hidden from official accounts: Hyrom’s soundscapes, the nightly rumble of the goods trains carrying toxic chemicals, vacant lots adapted as basketball courts and soccer fields by black and Hmong youth, and the searchlights of Harley Davidson security details.

Figure 21. Today’s 1304 North 37th Place. © Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures Field School. 2020.

Our story ends on a positive note. In 2017 Nery and Thyren Stephen bought the boarded up building (figure 21). He bought another building on Vliet Street to begin his new bakery. Our engagements with the community opened up new ideas for the park and in 2018, MKE Plays, a city initiative received grants from the city, Walt Disney Corporation, and National Recreation and Park Association (NRPA) to redesign Foundation Park.

Author’s Note:

This research is collaboratively produced with student researchers at the summer Buildings-Landscapes-Cultures field school and other courses. The project was funded by generous grants from the Wisconsin Humanities Council, the David and Julia Uihlein Charitable Trust, and the Wisconsin Preservation Trust. Student researchers were supported by multiple SURF grants from the UWM Office of Undergraduate Research at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. Sincere gratitude is due to community collaborators and residents of Washington Park and Martin Drive E neighborhoods.

NOTES

[1] Sassen argues that flatlands are not isolated spaces. They mark an edge or discontinuity, between private and public space, economically profitable property and communally valued street, structure and infrastructure, —yet their deviancy emerges out of a seeming lack of a hierarchical relationship to the public realm. Additionally, flatlands are “spaces of silence, of absence” where the generative syntax of the American city is disrupted.

[2] Fieldwork rigor, that very quality that helps us interpret buildings as material culture, also conceals alternative ways of seeing, knowing, and being. It fixes our perspective and space to account for movement, displacement, and erasure as forms of building. It separates buildings and their material reality from affect, feelings, memories, and lived experiences.

[3] Oscar Newman used the term to describe, “[...] a residential environment whose physical characteristics-building layout and site plan-function to allow inhabitants themselves to become the key agents in ensuring their own security.” Oscar Newman, “Design Guidelines for Creating Defensible Space” (Washington: National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, U.S. Dept. of Justice, April 1976), 4.

[4] African Americans had started to migrate to Milwaukee during the interwar era, between 1915 and 1945. By the thirties, Federal redlining maps identified this area as C13, a predominantly German neighborhood that was “slowly going down” because of the potential “infiltration” [their words] of Blacks. Milwaukee’s real estate practices, influenced by these maps, perpetuated segregation. It was only after the Second World War that a second wave of black migration brought a sizeable number of African Americans into the city. Paul Geib, “From Mississippi to Milwaukee: A Case Study of the Southern Black Migration to Milwaukee, 1940-1970,” Journal of Negro History 83, no. 4 (1998): 229-48.

[5] Urban scholars from Joachim Schlor to Peter Baldwin argue that historically, we have been ignorant of nightfall.