The Prison as Tourist Site

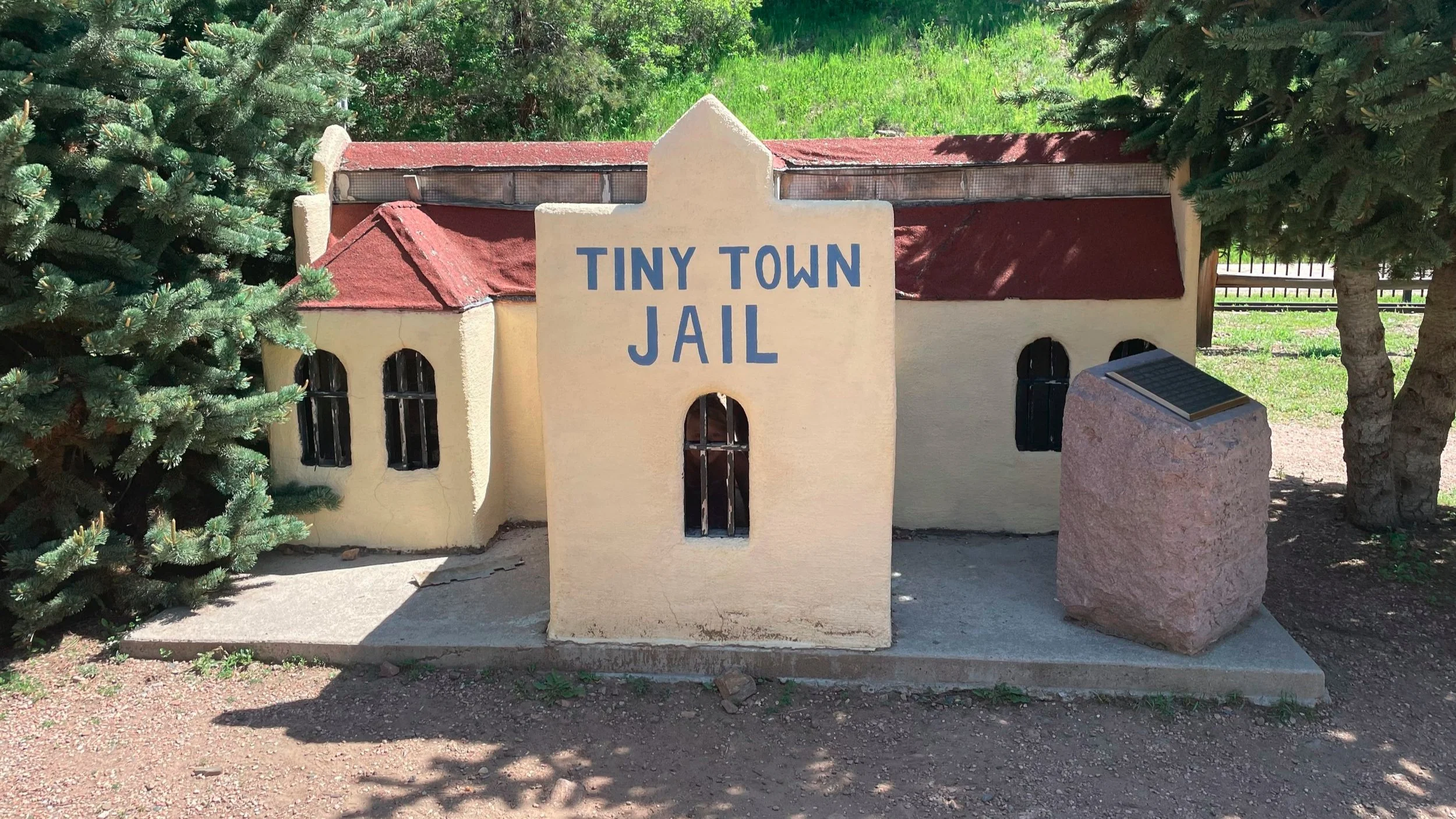

There is a tiny jail in a tiny town at the foothills of the Colorado Rocky Mountains (Figure 1). Originally built by a Denver businessman in 1915 for his daughter, Tiny Town has changed hands several times over the past 100 years, surviving floods, a fire, and most recently the lockdown related to Covid-19 pandemic. Visitors to Tiny Town today can ride a vintage locomotive that takes you by the town’s miniature architecture, which include a gold mine, Victorian mansions, an opera house, saloons, and stores. Children, Tiny Town’s primary audience, delight in the experience of being bigger than buildings, peering into little worlds with the vantage of a giant as if they are Gulliver among the Lilliputians or Alice after she has had her cake. Growing up in Colorado, I loved Tiny Town and visited several times. I took my own children on a summer vacation and enjoyed the memories the place brought back for me.

Figure 1. “Tiny Town Jail,” Tiny Town & Railroad, Morrison, CO. Author’s photo, 2023.

But that jail. As a scholar of critical prison studies where to begin? The Tiny Town jail is one of the older buildings on the property with a plaque curating visitors’ engagement by explaining the building’s connection to Colorado history. Its design inspiration was the Denver County Jail, a late nineteenth-century building that originally held up to 400 prisoners (Figure 2). Though razed in 1963, the Denver County Jail was constructed as Denver began its transformation from Gold Rush town to a City Beautiful. Tiny Town memorializes that history in miniature. The cathedral-like façade of the county jail was simplified in the Tiny Town version, replaced with a painted label explicating the building’s carceral function.

Figure 2. Denver County Jail, 1930-1940. Courtesy of the Denver Public Library Special Collections X-20608)

The Tiny Town Jail is also one of the few buildings that children can actually crawl into. The outline of my youngest child’s head can be observed behind the barred window in the photograph (see Figure 1). They were scared to go in at first—fearful that they might not be able to get out in case it was a “real” jail—, but couldn’t resist the allure of playing in the building.

The experiential takeaway for me as I reflected on this miniature jail, having engaged with prison histories for the past fifteen years, was that even within a playful tourist attraction designed for children the need for disciplinary space is made evident. The existence of a town (even a tiny one), in other words, presupposes a building for the punishment of offenders. Another way of reading the Tiny Town Jail is to see it as exemplary of the insidiousness of the prison, which has crept into culture, effectively signaling its permanence for society’s youngest members.

Adults, too, can absorb the prison as a cultural artifact. Decommissioned jails and prisons around world have been repurposed in a variety of ways, acquiring surprising social functions. Even in the college town where I work, a Southern bistro now occupies the building that once served as the town’s jail, and prior to becoming a restaurant this former jail was home to a fraternity. Of course, all buildings have the potential for afterlives. Architecture, as it is aligned with physical and material longevity, often appears to outlive its original function and can be reimagined in the service of something new. But can a prison building ever truly erase or escape its history? Should it?

One answer to these questions has been the relatively recent practice of converting the prison into a museum. Around the world, prominent prisons, which for a variety of factors were viewed as no longer serving their purpose, were shuttered with any remaining inmates transferred on to other facilities. However, these massive buildings lingered, often falling into disrepair until a government or a historical society began the process of museumification. In the US the most iconic prison museums—Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay and Eastern State Penitentiary in the heart of Philadelphia—together see millions of visitors each year. Interestingly enough, both prison museums draw attention to their incarceration of gangster Al Capone—a criminal celebrity with a robust popular culture life (Figure 3). Other famous prison museums include Seodaemun Prison History Museum in South Korea, the Cellular Jail in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Robben Island Museum in South Africa, Presidio Modelo in Cuba, and Kilmainham Gaol Museum in Ireland, to name a few. In addition to its status as a museum, the main hall of Kilmainham Gaol has even appeared in prominent films such as The Italian Job (1969) and Paddington 2 (2017). This cinematic afterlife further elevates the former prison’s status as a cultural artifact (Figure 4).

Figure 3. “Al Capone’s Cell,” Eastern State Penitentiary. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 4. “Main Hall,” Kilmainham Gaol, Author’s photo, 2023.

Like all museums, the prison museum has a mission. The aforementioned prison museums strive to memorialize not only the history of incarceration in their respective countries, but also tell the story of the prison’s role in incarcerating prominent political activists who opposed colonial and totalitarian regimes. The existence of such prison museums around the world has given rise to a unique leisure activity known as prison tourism. Prison tourists wander through buildings witnessing the preservation of architecture’s capacity for punishment. Granted access to formerly elusive spaces the prison tourist, like my child crawling into the Tiny Town Jail, can imagine themselves incarcerated, but happily vacate the prison when the tour is completed. These prison museums can then be said to hold on to their carceral histories, transforming the carceral experience into a cultural one.

The project of penal museumification unifies two of the most significant developments to emerge during the Enlightenment—the reliance on modern incarceration as punishment and the introduction of museums as public centers of knowledge. As Nicole Fleetwood has shown the both prison and museum remain “foundational to the conceptions of freedom, aesthetics, and subjecthood that continue to frame contemporary life.”[1] The prison museum doubles down on these values, and the prison tourist absorbs the historicization of punishment as a knowledge- gaining exercise.

“... can a prison building ever truly erase or escape its history? Should it?”

There is great value in the experiential. Occupying a cell and living enclosure, even for a brief moment, forces one to confront the horrific spatial reality that is modern incarceration. However, there are times when prison tours begin to border on camp, as museum programming, which caters to niche experiences, loses sight of the gravity of the history it disseminates. Halloween-themed events at Eastern State Penitentiary, for example, have come under fire for their flippant tone, and such critiques of dark tourism raise important concerns about our cultural desire for witnessing suffering.

I have complicated feelings about prison museums. They are invaluable resources for my work on prison histories, preserving spaces and objects for me to study that might not have been considered worthy of saving because of their association with punishment. I also understand that the prison museum must develop programming that ensures its sustainment. However, prison museums exist in countries where active prisons remain. I wonder then if the prison museum inevitably ends up affirming incarceration’s importance for the prison tourist? These museums also do little to equip the tourist with an imagined alternative to the prison or a future that includes abolition.

Christina Sharpe writes that “Every memorial and museum to atrocity already contains its failure.”[2] Can the museumification of the prison be said to be a futile exercise? Is the failure of modern incarceration obscured or even supported through the historicization of the prison as a tourist site? I continue to think on answers to these questions.

Citation

Waits, Mira. “The Prison as Tourist Site.” PLATFORM, April 15, 2024.

Notes

[1] Nicole Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020) 27.

[2] Christina Sharpe, Ordinary Notes (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023), 38.