"The Lost Generation": Trauma and Rehabilitation Cyclone Shelter, Part 1

Who are “The Lost Generation”?

Since 2017, the Kutupalong refugee camp, located 2.3 miles from the shores of Cox’s Bazaar, has grown from a temporary settlement of 34,000 to a city of 1.2 million housed within 33 highly congested camps. The Rohingya, a Muslim cultural group originally from the Rakhine state in Myanmar, are considered an ethnic minority population who have lived in the Buddhist-majority state for centuries, facing violent discrimination and armed conflict since August 2017. While years of persecution have caused many to flee to Bangladesh’s eastern coastal district through forced mass migration, the Rohingya have continuously been denied citizenship by their parent state, and are subsequently identified by the UN as “the world’s largest stateless population”.

Figure 1. Two young men at the Kutupalong Camp. Photography by Reem Nassour. September 2023

For those who live in the Kutupalong camps (Fig. 1), the feeling of anger and injustice is palpable above all else - and none more so than among its young adult male population. Gang violence, human trafficking and illegal trade dominate the site after government officials and aid workers leave at the end of the day - and since formal education in the camps end at ‘primary level’, young men between the ages of 12-18 are left streetside with no skills, care, or purpose and so, become targets of gang recruitment.

Last year alone, 53 members of the Kutupalong camp were murdered in multiple counts of gang warfare - although the unofficial numbers are thought to be at least triple that figure. In 2019, a fire which claimed the lives of 850 and burned down over 10,000 shelters was thought to have been started by an arson attack on a targeted group of individuals by the gangs themselves. Grooming, which starts as young as 12, when children are left without any opportunities for secondary education or work, escalates to full scale violence by the time they are 15. As boredom turns to frustration, frustration turns to anger, and anger turns to violence, the young boys of Kutupalong, often referred to as ‘The Lost Generation’, are recruited with the promise of ‘brotherhood’, ‘power’ and ‘agency’ over their slowly deteriorating futures.

Figure 2a. Satellite image location of the Kutupalong Refugee Camp (top). Imagery from Google Earth. September 2023.

Figure 2b. Annotated image indicating the journey across the Naf River from Myanmar to Bangladesh (bottom). Imagery from Google Earth. September 2023.

Figure 3. Series of satellite images describing the camp’s urban evolution from 2002 to 2023. Imagery from Google Earth. September 2023.

Meanwhile, the imminent threat of natural phenomena continues to threaten the camp. Since the Rohingyas have occupied the region, there have been over 14 cyclones, 5 camp-fires and 4 flash-floods, each causing severe loss of life and irreparable damage (Figs 2-3). It is at this intersection, where natural disaster, political upheaval and social detritus meet, that our project situates itself with the hope of bringing light to the ongoing plight of the Rohingyans, and specifically, the future of its young adolescent population.

“The Rohingya have continuously been denied citizenship by their parent state, and are subsequently identified by the UN as “the world’s largest stateless population.””

Kutupalong, The Temporary City

Over six years after their mass exodus from Myanmar, the Rohingya have settled on what was once forest lands stripped bare to make way for ‘temporary’ conditions of refuge (Fig. 4). The Kutupalong-Balukhali camps in Cox’s Bazaar, an area of approximately 2,500 square kilometers, were built quickly and haphazardly on what was once a hilly jungle. The mass extraction and removal of trees from this once fertile site left behind hills of rootless soil upon which temporary shelters were constructed and multiplied exponentially over just five years. These geological and environmental conditions create vulnerable landscapes that are prone to landslides and flooding (Fig. 5). The ever-growing sprawl of shelters constructed mostly out of ‘temporary’ and ‘deconstructable’ materials such as tarpaulin and bamboo have created squalid conditions in the camp and leave those who reside within them vulnerable to disasters across the field; from fire, to flashfloods, to landslides, to cyclones.

Figure 4. View of the temporary shelters at Camp 10. Photography by Reem Nassour. September 2023.

Figure 5. Construction of retaining walls along Camp 10 hills by re-trained refugees. Photography by Reem Nassour. September 2023.

During the visit to the camp, a few simple, but lasting observations were made. Although we had visited with the Institute of Migration (IOM) and several aid workers who had worked across the field, our entire party was chaperoned by three armed Bengali military guards. It occurred to us then that the figures, statistics and data we had spent the previous weeks studying were ill-equipped to prepare us for the reality of the camp itself. Among other things, the physical geography can be described as a sea of precarious temporary housing resulting in what one would describe as a dense, disorientating experience (Fig. 6). Informal and almost organic economic systems seemed to flourish within the camps where roadside stalls, rickshaw bicycles and electrical outlets lined the road and “buyers” and “sellers” painted a picture of an ever-growing social structure.

Figure 6. Embroidered artwork of camps 10, 11 and 12 as illustrated by resident artists Photography by Reem Nassour. Art from Rohingya Cultural Memory Center, Kutupalong. September 2023.

While materials were used by the residents resourcefully, the bamboo and tarpaulin shelters were physical signs of a place designed and controlled by protocols of impermanence. The settlements within Cox’s Bazaar not only take up thousands of acres of land but have put an undeniable strain on local resources. The Rohingya’s return to Myanmar is uncertain, while their host nation, Bangladesh, considers them a burden. Tensions have increased between the local population and the refugees resulting in numerous restrictions - both economic and spatial (Fig.7). Fences border the camps turning them into isolated enclosures within which employment and education opportunities are limited, furthering the sense of temporality and enforced impermanence of the Rohingyan settlements in Bangladesh.

Figure 7. Hand-drawn map describing the inseparability of people and place throughout Bangladesh. “Folkculture Map”. Drawing by Reem Nassour and Nabil Haque. October 2023.

The Architecture of Transition: Cyclone Shelters for Bangladesh’s Eastern Coast

The Bay of Bengal and its communities have witnessed and experienced some of the deadliest weather disasters recorded in history. Every year cyclones impact the 710 km-wide coastal plain and the 40 million people that inhabit it. Cyclone Bhola of 1971, one of the deadliest natural disasters ever recorded, and Cyclone Gorky of 1991 are testaments to the profound power and severity of these storms - claiming over half a million lives between them. As a response to this critical condition, the Bengali government has built roughly 14,000 cyclone shelters along the nation’s coast that have the capacity to accommodate around 2.4 million people during these disasters (Fig. 8). With much of the country’s territory lying less than five meters above sea level and its low-lying deltaic geography, Bangladesh has become a transformative waterscape that has had to continuously negotiate increasing population pressures, habitable geographies and natural disasters, and material cultures that continue to converse with the land’s material conditions.

Figure 8. Archive Image of the damage to homes in Patharghata village after Cyclone Bhola. Imagery from The World Bank. November 1970.

Coined by NGO’s and global aid organizations as “cyclone shelters”, these structures often provide more than one purpose. During our visit in September 2023, we observed that the structures are usually built on high stilts and elevated from the ground with piloti-style columns, primarily serving as a temporary refuge space for communities during cyclones (Fig. 9). We spoke with families and understood the difficulties faced when they must leave their homes with their belongings and seek out shelter for days, weeks and in some cases, months at a time depending on the severity of the storm. In the months before and after cyclones, however, these structures take on a secondary function as schools, community centers, clinics or mosques, depending on the demands of the communities they are situated within. Regulations and policies have generated a standardized typology for these cyclone shelters. We discussed these policies with government stakeholders who acknowledged the potential for further design capacities within them so that they can begin to better account for dignified space allocation per person, with attention to detail and comfort that is often overlooked in times of need.

Figure 9. An image of a typical cyclone shelter in Bangladesh. Imagery from the Pulitzer Center.

The Advanced Design Studio ‘Architecture of Transition’, led by Marina Tabassum at the Yale School of Architecture in Fall 2023, sought to critique, reassess and offer alternate design proposals for the typology of the “multipurpose disaster shelter” in Bangladesh. Across four different coastal sites with varying geographies, topographies, elevations and communities, the studio put forth design proposals that responded to contextual, cultural, and economic conditions of the communities within those sites, with a particularly focus on how the shelters could be used outside the event of a cyclone itself. Of the four sites, we decided on Camp 10 in the Kutupalong Refugee settlement as the focus for our design efforts. This site had suffered from numerous cyclones and natural-disaster related events in the last three years of its existence, and was in desperate need of new, innovative design solutions.

A Multi-Purpose Cyclone Shelter for Camp 10

Rather than taking an analytical approach to the project, we positioned ourselves in respect to material and cultural processes already latent and flourishing within the site (Fig. 10-11). Indeed, the Rohingyans continue to display remarkable acts of cultural resilience against the forces which have contained them. Although much of the Rohingyan material culture is passed down through oral tradition, the act of making baskets, clay pots, weaving to land-forming terraces and infrastructure, became a liberatory process for the community.

Figure 10. Image catalog of objects made by refugee artists at the RCMC. Imagery from the Rohingya Cultural Memory Center, Kutupalong. November 2023.

Figure 11. Image of hand-made tiled floors at the Rohingya Cultural Memory Center. Photography by Reem Nassour. September 2023.

As a result of the camp’s proximity to the coast, the fertile ground on which the site is built is rich with alluvial-clay soils, and therefore cultivates an extremely vibrant culture of pottery. Former fishermen who have used their dexterity to transform reeds, vines and dried leaves into intricate baskets and woven sculptures for daily use and former wood-workers who have reformed driftwood leftover from government building services into miniature wooden objects, offer a portal into memorializing the lives they left behind in the Arakan State. These objects, and more, have found a home at the Rohingya Cultural Memory Centre, built in 2019 by Bengali architect Rizvi Hassan, to champion “the lost identity of the Rohingyan people, and to cultivate a new sense of identity in a condition of the utmost adversity.”

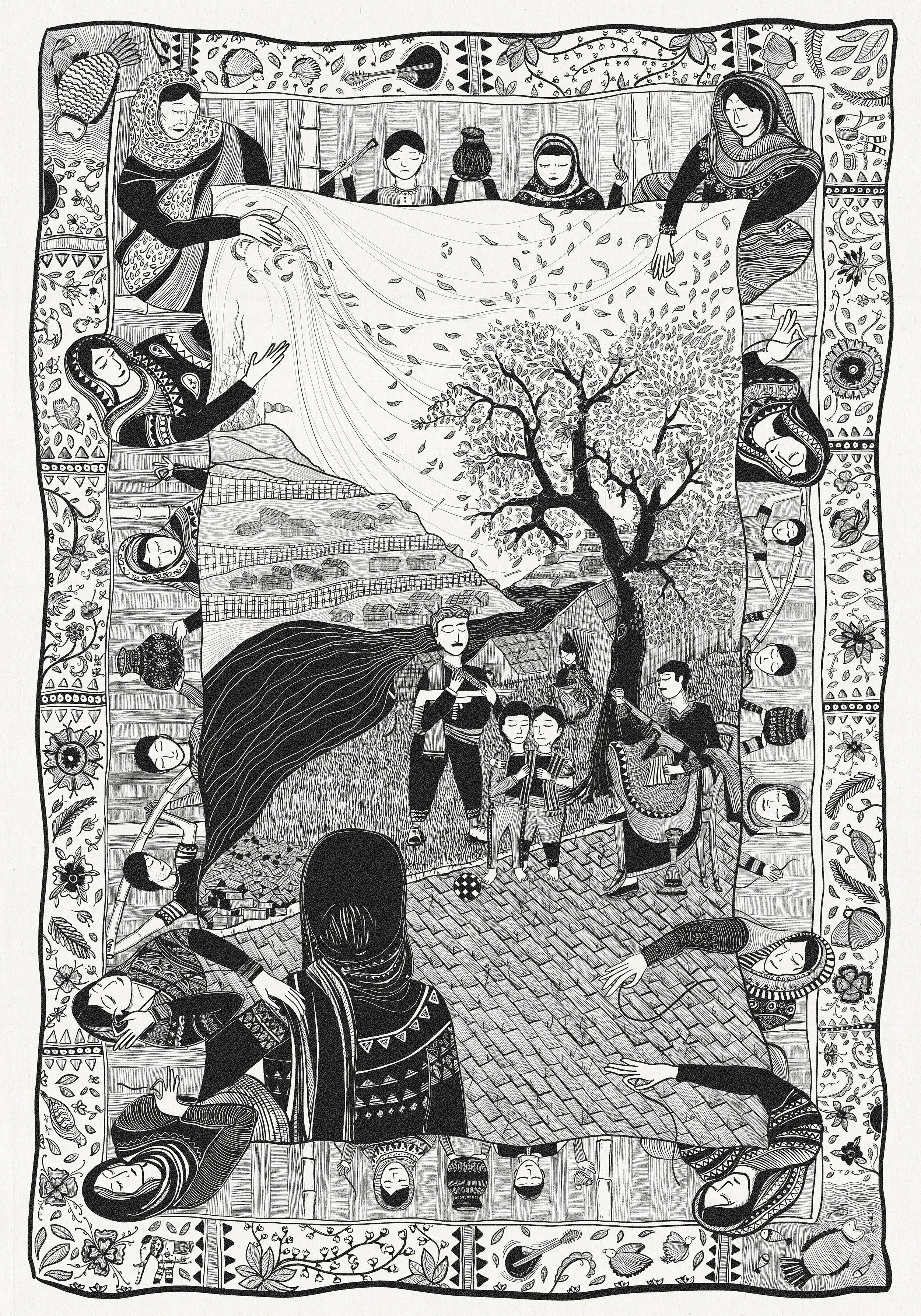

Our research on the site focused heavily on these objects and our design intentions were inspired by their production. Among the pots, baskets, paintings and musical objects we studied, it was the ‘Nakshi-kantha’, a female-led craft of embroidering quilts that symbolized the power of making for marginalized communities today (Fig. 12). The word kantha refers to the type of stitch required to join recycled pieces of cloth together, but the craft itself is passed through generations of mothers and daughters, grandmothers and grandchildren, through word of mouth.

Figure 12. Image of a woven Kantha, made by young Rohingyan Women, at the Rohingya Cultural Memory Center. Photography by Reem Nassour. September 2023.

From corner to corner, the elderly women stretch the fabric and create the beginnings of a tapestry. Almost like a canvas, the younger generations join along the perimeter of the piece and are taught to weave the stories of their past and the hopes of their future. The method in which the kantha is stitched means that multiple hands must work on it at the same time, and so in the act of making it, the women relinquish the role of the author and celebrate collective endeavor instead. In reading the kanthas as a coming together - of multiple hands, multiple stories, men and women, old and young, we saw a direct parallel with our own attempt to collect people together in one space both during the event of a cyclone, but also in how the building could be built, made and maintained by the community themselves. In thinking through the requirements of a shelter that responds to risks of high wind speeds, fire, lightning, and flooding the early design sketches explored the simple act of submerging a large footprint at the hilltop.

Using the kantha as both a framework for the spatial organization of the building to come and its capacity to narrate stories of place, stories of making, and stories of healing, the project’s drawings describe a cyclone and rehabilitation shelter that rethinks the government’s typology for shelters across the region. The drawings, arranged as a triptych, speak to the three main qualities of the project.

The first, “Life in the Camp” describes the latent issues of gang violence that prevail throughout Kutupalong, represented through a scene where two young boys are groomed by older men as the mothers helpless gaze looks on (Fig. 13). The background depicts the scenes of an imminent cyclone as winds seemingly howl and claw at the ground and trees beneath them.

Figure 13. A Sequence of hand-drawn narratives. “Life in the Camp” Triptych 01/03.Drawing by Reem Nassour and Nabil Haque. October 2023.

The second, “The Shelter as Multi-Sited Infrastructure”, speculates the project’s capacity to operate as a primary shelter, a central piece of infrastructure, and a replicable template for smaller shelters than can be erected across the camps (Fig 14). Cutting through the hill upon which the primary shelter is sited, water collected by the building spills and flows across canals spread throughout the camp and demonstrates the shelter’s ability to operate as a piece of integrated water infrastructure in equal measure to its role as a shelter for refuge. Ranging in size and scale, the shelters scatter and ground themselves in various forms and conditions.

“The word kantha refers to the type of stitch required to join recycled pieces of cloth together, but the craft itself is passed through generations of mothers and daughters, grandmothers and grandchildren, through word of mouth.”

Figure 14. A Sequence of hand-drawn narratives. “The Shelter as Multi-Sited Infrastructure” Triptych 02/03. Drawing by Reem Nassour and Nabil Haque. November 2023.

The third and final drawing of the triptych, “Life within the Shelter” narrates the experience of building when not in use as a shelter, serving as a multigenerational training center where adolescent boys can continue their education (Fig. 15). Represented through planimetric forms, figures populate the spaces within them while objects are made, food is cooked, songs are sung, and identity is found in this space of refuge and resistance.

Figure 15. A Sequence of hand-drawn narratives. “Life within the Shelter” Triptych 03/03. Drawing by Reem Nassour and Nabil Haque. December 2023.

Dealing both with the layered, violent and precarious situation of the camp alongside the prosaic concerns of designing disaster-relief shelters, “The Lost Generation” Trauma and Rehabilitation Shelter aims to generate a territorial infrastructure which provides education, refuge and dignity for Bangladesh’s most vulnerable population, in its most vulnerable condition. In educating themselves and in sharing their experiences with others, the project provides a space where “The Lost Generation” are protected against the systemic and physical violence which surrounds them - while simultaneously giving them a platform to imagine their future.