Turning Towards Action in Landscape History

In 1999, the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians published a special issue devoted to the field of landscape history at the start of a new century. In that issue, Dianne Harris argued that over the 1990s landscapes became “important documents for understanding the development of national, social, and personal identities” across political, ecological, and ideological questions. This broadening of the field that Harris identified over twenty years ago continues today. One of the central developments in landscape history, as Sonja Dümpelmann noted in an article for Landscape Research in 2011, was an affinity with environmental history. In this first of a series of two conversations on landscape history, four early-career scholars reflect on developments in the field and its institutional position over the course of their graduate educations and early careers. This will be, we hope, an opportunity to reflect on the stakes and concerns of the field and its future.

The first conversation took place on June 21, 2022, over Zoom with John Dean Davis, Charlotte Leib, Margot Lystra, and Pollyanna Rhee. The conversation centered on the position of landscape history within architectural history and other fields, especially environmental history, science and technology studies, and labor history.

Pollyanna Rhee: Why don’t we start by generally talking about how each of us think about landscapes in our work and how it relates to landscape history as a whole. Another way of posing this question might be to ask, “why do we think landscapes matter?”

John Davis: I came to landscape from kind of a different angle than being interested in specifically designed gardens or conserved landscapes. I came at it from the history of engineering. One of the things I realized is that engineering is about altering the basic dynamics of a place. It’s about altering the very basic physical qualities of a place, the hydrology, the way that matter acts under gravity, the way that the water and soil behave. The useful thing about thinking about things in terms of landscape is that there are all these human bits of culture around those basic dynamics, so if you change the dynamics you are also changing the bits of human culture.

Charlotte Leib: My interest in the idea of “landscape” and in landscape history began during my Master’s degree in landscape architecture, when the work of David Nye and Sonja Dümpelmann first exposed me to the idea of studying landscapes as technologies. This was revelatory to me at the time. Once I started to conceptualize landscapes in terms of technological invention, it began to bring me closer to the field of cultural history. As I was exposed to the work of landscape historians like Thaïsa Way and Beth Meyer, and earlier scholarship on vernacular and cultural landscapes, and landscapes of power, it became clear that landscape as a concept is complicated and fascinating, and holds a lot of meaning. Since then, I’ve maintained an allegiance to working with the idea of “landscape” because I find that the term, with its multiple visual, material, and political valences, is one that can bring a variety of ideas and scholarly communities together.

Pollyanna Rhee: I don't come from landscape with a design degree, but have been interested in the ways that people use the landscape to project or articulate their political and social claims and justify it through relationships in the land. I think that's actually one of the challenges of studying landscape because it doesn’t seem as hard or quantifiable as something like money. But how does landscape actually work or help form social ideas? If we think of landscape history as a type of cultural history, we can ask questions about how people made sense of landscape and use the landscape to justify their interventions in it.

Margot Lystra: Like Charlotte, I first encountered landscape history and ideas while studying for a Master’s degree in landscape architecture. Since then, my definition of landscape has broadened a lot. At this point I think of landscape-making as relational in a very open sense: any action that intentionally makes new forms of connection with the more-than-human world is making some kind of landscape. These new forms have both imaginative and strategic dimensions. If we're considering the role of a landscape site within urban life, for example, negotiation among different stakeholders involves imagination, involves asking what the landscape could be. I suppose this is to say that I also largely engage landscape history as a kind of cultural history.

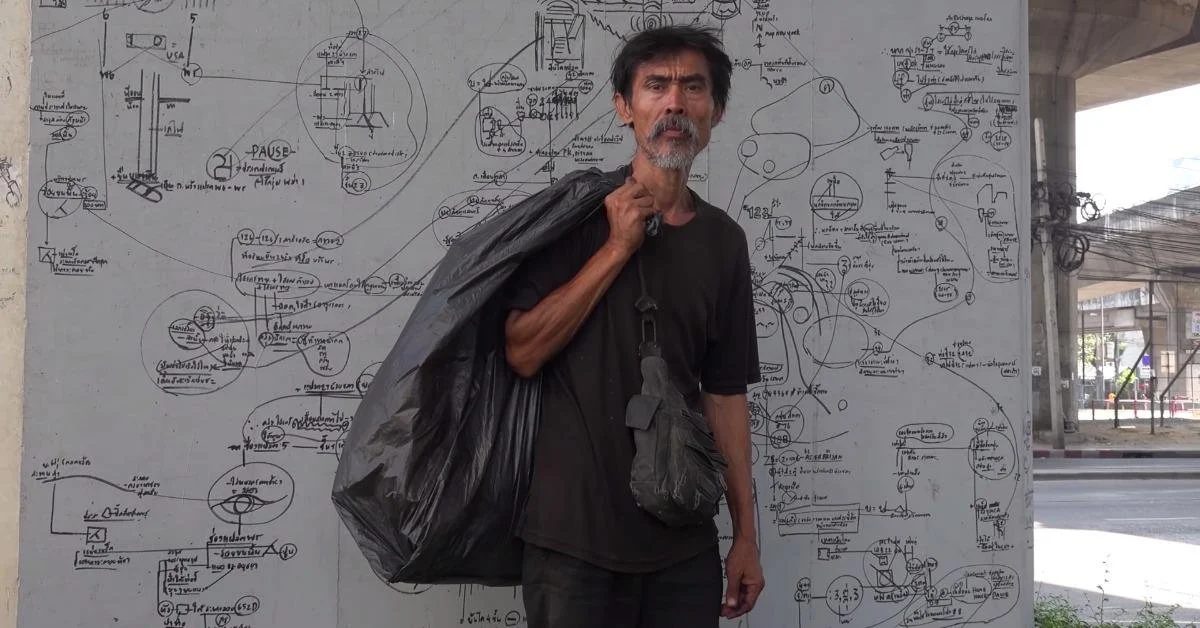

Figure 1. Old growth oak woodland in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, 2015. Photograph by Margot Lystra.

How to Do Landscape History

Rhee: We're all interested in the interlocking factors that studying landscapes bring together. History provides a way into telling those stories while making aesthetic, financial, and political arguments. How do we describe those intersections between these cultural and intellectual factors and what’s happening on the ground? I think that's one of the methodological burdens that makes landscape history exciting but also difficult.

Leib: Landscape history now seems to be conditioned by a care for vernacular landscapes and landscapes of social difference. Recently, landscape studies scholars have also begun to look to the work of Native American and Indigenous Studies scholars as we rethink categorically what land is or could be. Is land a thing? Or a constellation of kinship relations? Thinking through “what’s happening on the ground” or through ground—through kinship relations and, often, colonial incursions into and upon these relations, is one way to think through what it means to do landscape history. More broadly, we could think of landscape history as the study of how different visual and material cultures intersect and manifest in grounded ways at different scales and temporalities.

Davis: I think there's an institutional question that's important here, too, especially in the U.S. context. I hesitate to ascribe so much institution building to one guy, but the fact that John Brinkerhoff Jackson was at Harvard and at Berkeley and left protégés everywhere has shaped the field and definitely slanted it towards the vernacular. This background plays in a role in how we relate to the profession of landscape architecture, to environmental historians, and history departments.

Lystra: Another institutional influence is the longstanding association between landscape history and professional landscape programs. This affiliation has clearly influenced how landscape history has been practiced in the past, though I do think it is getting tested in new ways today by our field’s increasing interdisciplinarity.

Davis: Sometimes I don't know what I have to say to the landscape architects because I'm not a landscape architect and I don't have an MLA. My PhD is in the history of architecture. I think the thing that is interesting about my current appointment is that they were willing to take a chance on an expanded idea of landscape architecture. I think that it says something about landscape architecture as an academic pursuit that departments are willing to have historians who might not study specific landscape architects but might be more interested in other processes of landscape making.

Leib: If we think about the history of landscape architecture, it has a different nexus from architectural history because the practice of landscape architecture stems from diverse lineages. Military, agricultural, technological and everyday practices have all shaped how landscapes have been designed and built in the past. Asking how designed landscapes have been shaped, to what ends, and by whom results in different answers than if we ask the same question about buildings. And of course, there is often not a hard-and-fast line between a building and a landscape. As more people experience landscape change and land loss due to climate change and concurrent political conflicts, landscape historians can help to unpack how and where people place themselves in relation to land and community, and how that affects how spaces are shaped, how power transits, and how citizenship and landscape values are defined. The field’s diverse lineages and the interpretive flexibility of what a “landscape” is or could be gives landscape historians the opportunity to continually expand and reinvent the field for each subsequent generation.

“If we think of landscape history as a type of cultural history, we can ask questions about how people made sense of landscape and use the landscape to justify their interventions in it.”

Rhee: I wonder if, especially for those of us connected to design departments, how our broad definition of landscape compares to the design side of our programs. Are conceptions of landscapes equally broad? John and I came from an architecture PhD program, but I always thought I would work on topics related to environmental history and its relationship to architecture. In a certain way, landscape could be the midpoint between those two fields. But I also found that many of my classmates consider themselves working more on landscape rather than architecture. Or they work on urban forms, oceans and ports, national parks, and other subjects that arguably would be more within the purview of landscape history. Over the past several decades, landscape historians have become more committed to asking questions about colonialism, capitalism, race, and labor. Architectural historians still work on architects and buildings, but there are a lot more who see landscapes not just as the ground around buildings, but actually the location to analyze these concerns.

Davis: I want to emphatically agree with that point because it's a trend that I've noticed, too. I think “landscape” does allow for people to get at definitions of political economy and assemblages of different concepts that are not as present in the typical, object-focused art history model. I think it's worth dwelling on the distinction between that kind of assemblage/political economy idea and environmental history’s methods. In the book I’m writing, I’m focusing on nineteenth-century engineers in the Reconstruction South (Figure 2). They don't have a concept of environment, but they do absolutely think about their actions on a territorial scale. They think about local politics, local economics, they think about the social dynamics of particular places—especially having to do with race and labor. They also think about weather patterns and how that affects the fluid dynamics of the area around them. They don't talk about environments per se, but they do mention landscape every now and then so they're thinking about it in these terms. Studying these engineers recovers the grittiness of architectural “building” history and intersections with labor history and material history within landscape history.

Figure 2. Navigation lock under construction at the Muscle Shoals Canal, Alabama, ca. 1889. Photograph courtesy National Archives, College Park, Maryland.

Sites and Scales

Leib: I think one of the powerful things about the term “landscape” is that it suggests both a scale and a site. The term “environment” is much more nebulous, suggesting a relationship between a body, either in the singular or collective, and its surroundings. I made an argument at SAH recently that the “landscape” scale—a scale that could be defined as smaller than that of a region, but larger than that of a single building or site—is a missing scale of analysis in a lot of history writing. I also argued that it’s not just that particular landscape scale of analysis that’s missing, it’s “landscape,” as an idea and material reality. But of course, as John notes, the terms “landscape” along with its cousin “environment” are slippery and do not always show up in the archive. And if they do appear, they may not make their way into a historian’s written work. It is up to the historian to consider whether they will engage with or retrieve some version of the concept(s) of landscape or environment in their work. As environmental humanities initiatives have been established at various universities, the term “landscape” has had tremendous uptake. But as it has entered into a wider orbit, the people using the term and redefining it are not always aware that there’s a large body of literature that already engages it. It’s a moment of opportunity for landscape historians, but also a signal of the field’s relative smallness.

Rhee: One of the comments I’ve gotten on my book manuscript is, why should we care about this one particular place that’s quite modestly scaled. One thing about landscape is that it allows us to mediate between localized questions, embodied landscapes, and the scale of individual experience and broader developments and social processes that occur not just in one place but across larger scales. There’s a perception of landscape history as being a field that studies isolated gardens, its design, plantings, and associated technologies. This can seem relatively insignificant, but then if every place is a landscape, how do we mediate between those scales? How do we talk about specific places, but also place them within broader economic, social, and political processes. This is a methodological issue where scale is central.

Lystra:. My historical work has tended to be urban in its focus. More recently, though, especially as I grapple with issues relating to climate change, I’ve started to engage a sort of expansion and contraction in terms of the scales of action that I research and analyze - much as you describe, Pollyanna. Environmental history has given us a great deal when it comes to interrogating connections across scales. This influence modulates landscape history in certain ways – it certainly impacts how we understand landscape sites. In a multiscalar context, “what is a site” becomes a very real question.

Leib: That question “what is a site?” suggests a guiding analytical framework that landscape historians can contribute to the larger field of history. Thinking of frameworks and ways of answering the question, “what is the site or why does the site matter?” is core to what we do as landscape historians. If we can be articulate in answering this question in print and when we share our work at conferences and teach students, we might be able to precipitate actions beyond the passive reading-about-landscapes-as-bounded-sites mode of engaging with landscape history and quite literally “scale” or expand the field. The way historians of technology have been able to expand the definition of what counts as “technology” while in turn expanding the demographic of who writes and engages with histories of technology can serve as a salient precedent for the field of landscape history as we consider what it could become. For historians of technology, expanding their field and making it more inclusive and representative of the cultures it studied and described required going beyond fixating on technological invention and the work of inventors. It meant conceptualizing technology in relation to sites, systems, users, and their values.

Davis: I’ll come to scale from a different angle. I had an experience recently where I shared a chapter from the book that I’m writing about rebuilding and essentially “moving” a river estuary. Those of us who study space also think a lot about the ways we represent them. We use maps, drawings, and it’s a given that they have an argumentative role in portraying mindsets, for example. But it’s not always clear to colleagues in other fields. I showed these nautical charts to colleagues in the history department and they had no idea what I was talking about. (It’s ok, that’s what these workshops are for.) So how do you convey the importance of visual materials, to both your own analysis and the perspective of your actors? Also, how do you convey the scale of something as big as a landscape to people who aren’t used to thinking from that vantage point? We have an opportunity to develop a visual language to address the question of scale and spatial comprehension. Using the power of spatial knowledge that we have at our disposal is an advantage. This is where the scale question hits the ground for me. It’s a methodological question of being able to articulate that clearly is really central in my work.

Lystra: I’d like to circle back to an earlier question, regarding what landscape history has to offer to environmental history and the history of technology. The visual dimension of landscape history distinguishes it from these other fields. Interrogating how environments are visualized, and why the visual matters: this is something we can contribute. The visual as a subject also brings up matters of aesthetics, to use that word broadly.

Rhee: A lot of the people I write on are mainly civil leaders, people not trained as architects or designers, but they use aesthetic arguments all the time to defend why there shouldn't be a housing development on this piece of land or to defend certain zoning or aesthetic controls on their environment. So they’re using a lot of aesthetic arguments with deep political and economic consequences. These arguments create a kind of vernacular aesthetic at various political and social levels.

“We have an opportunity to develop a visual language to address the question of scale and spatial comprehension. Using the power of spatial knowledge that we have at our disposal is an advantage.”

Methods, Today and Tomorrow

Leib: Being situated in a history department, it’s become clear to me only retroactively, after leaving the design school context, that the field of landscape history hasn't had the most legible or accessible methodological framework. Not that it needs to have one, but if landscape historians are asked by institutions and universities to wear different hats it’s essential to be able to explain coherently what landscape history is. There’s been this idea in landscape history that the field’s lack of a clear methodological framework is beneficial, making the field more inclusive of multiple forms of scholarship and ways of thinking about “landscape.” At the same time there’s also been a tacit expectation that landscape historians should have a Master’s degree in one of the design fields. That puts a high price tag on becoming a “landscape historian.” From where I stand, the field’s internal expectations and fuzzy working methods are more of a barrier than a boon to the field’s longevity and potential.

Lystra: Charlotte, I share your sense of difficulty here—on a pragmatic, nut-and-bolts level, it is remarkably challenging to operate in a landscape program as both a researching historian and a teacher of design studios. There is also an aspect of this challenge, though, that I find exciting. Working in a design context tilts theorization towards action, pedagogy toward action, research toward action. Having students who will go on to practice and to alter built environments conditions how one teaches history. Our research also relates to action, to implementation: the physical transformation of land, negotiation about the future shape of a city. What will be built, what will not be built? Facing towards action, past and future: this is something essential to our field.

John Davis: Margot makes a great point—this is why thinking about form as a kind of cultural production is really engaging for me. Cultural history methods would have us interpret landscapes as “forms,” iteratively produced and representative of aspirations and desires for the future. It lets us see what is conveyed by landscapes beyond a cynical or economically determined content.

Lystra: Related to that, I’ve been thinking recently about narrative, and the ways that historians hold on to a sort of impartial voicing. We have a tendency to maintain authoritative stances, even as we know that projecting “impartial” authority is deeply problematic. I would be thrilled to see landscape historians exploring and modifying our positions within our narratives more often. I’d like to see more subjective narrative voicing, more experimental storytelling: essentially, more embracing narrative as methodology.

Rhee: There is a certain accessibility to landscape history for a broader public. We all have experience with landscapes, historian or not. Writing landscape history is basically then just clarifying terms, categorizing thoughts. Whether or not people know it, we’re constantly making cultural assumptions and forming ideas about the landscape. So there’s an entryway into landscape history that doesn’t necessarily have to be super archival.

Figure 3. Prospect Park in late August 2022 after a thunderstorm and several weeks of drought. Photograph by Charlotte Leib.

Leib: Yes, we need more pluralistic, public-facing, and narrative forms of landscape history. Lately I’ve been trying to research and write landscape stories that foreground things that most readers might not immediately “see” in a landscape—things like plants, animals, energy, and the actions of communities of people and laborers who have been “backgrounded” or written out of American histories. I’ve also been thinking about climate change. There’s the idea that with climate change, we’re living on a damaged planet and that we’re living in the heat of the past. Those statements hold important truths, if we consider Earth to be one large monolithic landscape. But we also live in the space of smaller, dynamic landscapes—communities of people and things—that have the power to mediate and guard against the next two degrees of global warming. Through landscape thinking and landscape history, we can begin to see and sense finer-grained relationships more clearly. We can begin to act to intervene in relationships that are harmful, constraining, or colonizing. And we can do all this because landscapes simultaneously function as retroactive registers of past values and actions, and as projective media that have the power to shape future scenarios. They are constant canvases for the reinvention of value and of circumstance. While landscapes quite literally contain us, and our cultures of consuming, warring, and discarding, and they often constrain us, determining (to an extent) our actions, they also hold out hope for the possibility of alternative worlds (Figure 3).

Rhee: With that image in mind, I hope we can find more opportunities to come together like this to consider what landscape historians can do to turn toward action as we work to define what landscape history has been, and where it’s going.