Unlearning, Part I

This is the first part of the conversation from the Unlearning Workshop organized by the Central New York Urban Humanities Working Group, Dec 9, 2020.

The Unlearning Workshop, convened online on December 9, 2020, by Peter Christensen, Lawrence Chua, Samia Henni, and Lisa Trivedi of the Central New York Urban Humanities Working Group, was prompted by events surrounding Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s lecture, “Palestine is There, Where It Has Always Been” on October 5, 2020, at Cornell University’s Department of Architecture. Borrowing the term “unlearning” from the titles of several publications including Swati Chattopadhyay’s Unlearning the City (2012), Azoulay’s Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (2019), and the Black faculty of Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation statement “Unlearning Whiteness” (2020), the workshop was organized into three panels: Unlearning Sources, Unlearning Pedagogy, and Unlearning Institutions. Workshop participants Swati Chattopadhyay (University of California, Santa Barbara), Charles Davis II (University of Buffalo), Ana María León (The University of Michigan), Lesley Lokko (African Futures Institute, Ghana), Victoria Young (University of St. Thomas), and Mabel O. Wilson (Columbia University) engaged in a collective exchange about our agency as historians of the built environment in the process of acting consciously on and correctively as researchers, teachers, and members of academic communities. These colleagues shared their experiences, concerns, and hopes in an era of institutional change that promises the pursuit of justice, including that for Palestine.

Unlearning Sources

Peter Christensen (PC): In the workshop’s first session, Unlearning Sources, we tackled questions around how we conduct research and we take unlearning to heart as researchers. In preparation, I sent Swati Chattopadhyay and Mabel Wilson the following prompt: “One would expect that a key element in decolonizing research in architectural history and unlearning problematic habits would involve the utilization and invocation of new primary source archival materials of privileged actors, like states and museums. Please reflect on what those alternatives may be, including ethnography, digital analysis, or non-canonical stores of knowledge. From where we might we draw new knowledge that unlearns entrenched forms of knowledge? Please also consider what interpretive and analytical tools might differ for the researcher and why they might signify an emancipatory position.”

Swati Chattopadhyay (SC): For me unlearning sources is about three things: (1) Refusing the priority of imperial formations; (2) Shifting the vantage; (3) Changing the scale of space and time.

Take the example of this boundary wall next to a street in Kolkata (Figure 1). The surface of the wall, which contained political graffiti, has been whitewashed. How do we read this?

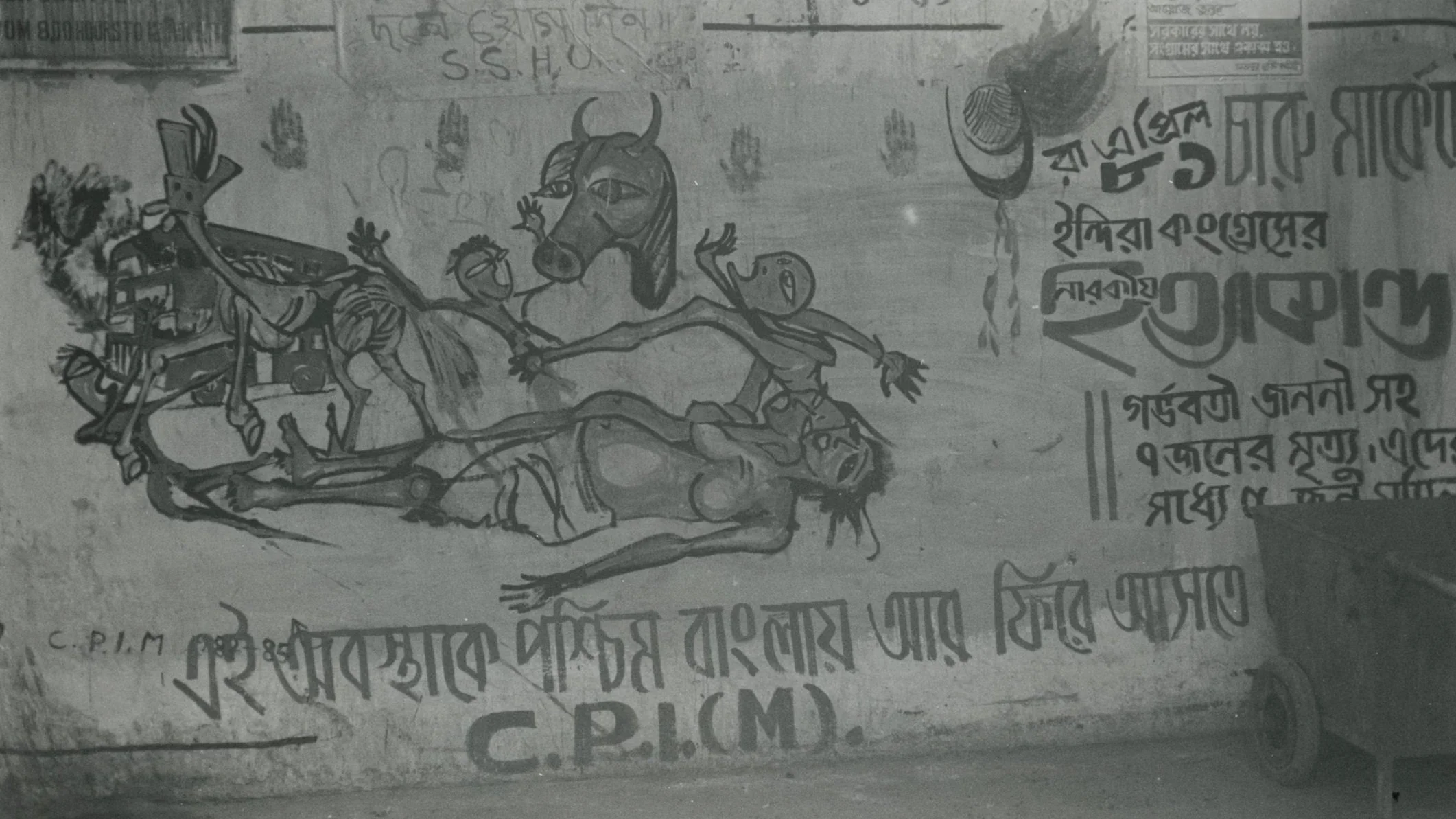

Political wall-writing was banned in India in 1992 by extending a 1976 Act that ostensibly aimed to protect private property. According to the state, wall-writing is a disfiguration of urban space. In 2006 India’s Election Commission enforced this law, noting that they are concerned about defacement of private property and political wall writing giving “an ugly look not only to the building but the whole city.” From that point of view prohibiting wall-writing is about rendering cities and in extension the body politic clean. It is about cleaning up the unruly public sphere and public space. What such argument obscures is the work that wall-writing does (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Whitewashed political wall writing; conjectural view. Copyright Jeremy White.

Figure 2. “Guernica”: Critique of Congress (I) by the Communist Party of India (M), Wall-writing, Kolkata, 1982. Photographer: Salim Paul. Courtesy of Chitrabani, Kolkata.

Thinking about the lethal environmental and social impact of post-1990s neo-liberal refashioning of Indian cities, in my book Unlearning the City I argued that to understand so-called global cities, we have to unlearn the terms we use in urban studies. My focus was the term infrastructure—what falls within the term’s purview and what does not. I argued that we cannot begin with the dominant discourse as a framing or jumping off point in such discussion. If we embark on a debate about road infrastructure and flyovers, pipelines and dams, on the terms set by state authorities, imperial and otherwise, we get mired in arguments about progress and development, economic fortunes and technological victories before we can broach the lethal consequences of contemporary city building.

If we abandon the premise that banning wall-writing is about clean cities (which it is patently not, but the cleanliness metaphor is telling), and rather accept that wall-writing’s threat resides in its ability to produce infrastructure, to forge new communities, we can launch a different discussion about public space. In her article on the graffiti of the intifada, Julie Peteet pointed out that the hastily painted wall writing in the occupied West Bank during the late 1980s and early 1990s, was a product of the spatio-temporal limits imposed by severe censorship and state violence. The wall-writing registered dissent and transformed the wall into a site of political performance. Such wall-writing was not only “resistant” but their mere appearance “gave rise to arenas of contest” in which West Bank residents became agents of a political process which was denied to them. The walls were transformed by graffiti and became interventions in public space—speaking to and forming audience communities by actualizing the act of reading on the street.

Political wall-writing takes the negative codes of closure, delay, and prohibition that define the boundary wall, and turns these into an open and immediate invitation to read and share. The applied texts and images do not destroy the wall. Rather, they change its materiality by transforming a boundary wall into a canvas on which visions of the body politic not sanctioned by the state can be articulated. These are small acts, whose aggregate impact is potentially immense, and threatening to the state.

Whether in the West Bank, Calcutta or Hong Kong, shifting vantage to everyday practice requires changing the scale of time and space within which we are habituated to think about the built environment. Here we are asked to pay attention to the temporal quality of these small acts: in this case the swift act of inscription, the momentary reading that produces readership in unpredictable ways offering pathways to rethink formations of the public. It compels us to attend to what I call small spaces. Small spaces are not always small in size, but they are fragments, products of division, isolation, exclusion. These are spaces that appear in the margins of the archive. The challenge of unlearning sources resides in how we configure and reassemble these small spaces and small acts.

My recourse to urban popular culture, however, was not about searching for new sources. It was about looking for a vantage from which to unlearn the terms infrastructure and public space and put these terms to a different descriptive task. This is to say, unlearning sources is not about finding a text or object that no one has seen before, and plugging it into a narrative that is at its core rotten. The evidence of things not represented is everywhere—in the archive and in plain sight in our everyday lives, and in the very sources we use to teach architectural history. There is little to be gained in gathering an archive of Black architects and marginalized actors, if that archive is constructed along the lines of colonialist history. While it may be worthwhile to uncover marginalized narratives through diligent research to redress the absence of those voices that have been erased from the archive, these documents and voices come no less unmediated than the ones from the dominant historical archive. Both require a practice of reading. And for me the question is what practice of reading do we bring to our work as we assemble our archive? The great potential of a project of unlearning sources is that it might help us reimagine the place of the marginalized by refusing the priority of imperial formations, shifting our vantage and attending to small scales and short durations.

Mabel O. Wilson (MW): I wanted to begin by addressing two problematics for unlearning and to think about the production of historical sources of evidence, archives, and the production of history from these archival sources. When I teach, “Questions of Architectural History I,” I like to challenge my students’ assumptions by reminding them that, according to Michel Rolph Trouillot, the past can be understood as “what happened” and “what is said to have happened;” the latter according to our received historical understanding. Trouillot and his seminal work Silencing the Past: Power in the Production of History, posits history as social production by agents, actors, and subjects: “The production of historical narratives involve uneven contributions of competing groups and individuals who have unequal access to means for such production.” This process begins with the making of sources--of fact creation, followed by the making of archives--fact assembly. Next occurs, the making of narratives--fact retrieval--and lastly, the making of history--the moment of retrospective significance. An analysis of this process of historical production according to Trouillot, “can uncover the ways in which two sides of historicity intertwine in a particular context. Only through that overlap can we discover the differential exercise of power that make some narratives possible and silences others.”

It's important to recognize that Trouillot wrote Silencing the Past in 1995 as a response to the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution, which for him represented 200 years of the silencing of the Haitian Revolution, rendered invisible and irrelevant in world historical importance. If the process of historical production begins with the making of sources, with fact creation and the formation of archives, one that privileged, as Swati pointed out, imperial histories of the West and ensconced whiteness as a key signifier, then how do we write histories of indigenous peoples and racialized others within these problematic sources and prominent silences? This is, I think, fundamental to the question of unlearning. Do the logics of “diversity” and “inclusion” undermine engagements with the problematic of how these sources and resources form? How do we write? How do we make counter histories? In my Black Studies proseminar we read Trouillot, as well as M. NourbeSe Philip’s poetry collection Zong!, together with Saidiya Hartman's essay “Venus in Two Acts.” Philip’s poem deconstructs a two-page legal document seen here that recounts a court case filed by the owners of the slave ship Zong, who in their journey to Jamaica veered off course and with food and water diminishing dumped more than 200 of their human cargo overboard. Since the slaves were legally things, not people, the owners of the Zong filed an insurance claim preserved in the case, Gregson v. Gilbert, which provides the only account of that atrocity. “Can this story be told?” asks NourbeSe Philip.

For Philip, locked in the archival document Gregson v. Gilbert is a story that, “can only be told by not telling.” Her actions reorganize its words, reorders the letters of Gregson v. Gilbert, ghosts words, redacts words and in her words, “mutilates” the archival document much in the same way she asserts that the fabric of African life was mutilated. Even if one finds a document in the archive that breaks the silence as Philip did, one still has to contend with the erasure that forms in the wake of the silence when one has to confront individual and collective acts of brutality and death consequential to the West’s project of indigenous dispossession and enslavement; a project that rendered racial others less than human and that rationalized the taking of life, labor, and land.

In writing about another slave-ship captain tried for the murder of two unnamed Negro girls, Saidiya Hartman characterizes the archive for these two young women as, “a death sentence, a tomb, a display, a violated property, as an asterisk in the grand narrative of history.” Like Phillips, Hartman asks, “How do we account for the violence that deposited these traces in the archive?” I argue that writing architectural history from these documents, ledgers of the enslaved or the treaties of settlement found in archives, will have to do more than tell a story. The historian must confront the epistemic violence embedded in the formation of these sources. Hartman recognizes that this might be “an impossible goal, redressing the violence that produced numbers, ciphers, and fragments of discourse.” Pursuing this, by addressing, recognizing, may come close to “ a biography of the captive and the enslaved.” With redressing the violence and silences in mind, how might we write histories of the built environment that tell the stories of hidden or erased sites, not only to give its inhabitants biographies, but also to recognize for them places of home, places of community, and how they might have imagined freedom?

PC: The word “unlearning” is not merely the title of your book, Swati, it is a kind of vantage point, or a strategy, and that's very much why we were inspired today because the approach goes beyond your book. You describe the city as a primary source material for unlearning, for example in looking at the wall and the words that are written on a wall as sources that might otherwise go un-looked at. Mabel, I was really stunned by NourbeSe Philip of the Gregson v. Gilbert case in which words are actually omitted, not mined or interpreted, but words are actually omitted to say something different from a document. Whereas the words in Swati’s case are being whitewashed from the wall so that they don't appear for very long, here the words are being erased and both of you are pointing to the modality of erasure, which almost seems counterintuitive, as a way of looking at sources. Perhaps you'd like to reflect on that for a moment?

SC: When I started the work on Unlearning the City, I explicitly described the problem as a lack of vocabulary. We don't have the vocabulary to talk about our cities because everything we use falls into this old mode of thinking about capitalist imperial cities, we haven't been able to undo that. So, yes, it is about looking for a new vocabulary, so we don't talk about slums as shitholes, we don't talk about flyovers and infrastructure as sort of emancipatory potential. My approach to reading the archive is very much influenced by Ranajit Guha’s “The Prose of Counter-Insurgency,” which says that the archive is itself a prose of counterinsurgency. So how do you read that? What is your technique? What is your reading practice? That’s what Hartman does, and what Mabel refers to—a brilliant understanding of how to read the archive when those marginalized voices have not been taken into account. They're not there in the archive. How do you honor that silence in the archive? What do you do with the silence? You cannot put content in there. You have to disassemble that silence. I think it is both about a vocabulary and the paucity of it. What kind of language strategy we can use to reassemble?. We have not been able to communicate this, otherwise we wouldn't be teaching architectural history the way we do.

MW: I completely agree with Swati. In my Black Studies seminar, we also read Toni Morrison, how she carves away at the English language and grapples with the question of the language. She targets the discourses that also produce the dehumanization and the subjection of racial difference, essentially, a kind of violence within language and subjectivity. We talked a lot about poesis, about making. How do you make within this complicated realm of language and material world wrought from violent extraction. Philip works with the archival document and its silences. She was trained as a lawyer, so she understood how the importance of language and legibility to the law. At first, as Philip recounts in the essay at the end of the book, she rearranged the words, then the letters. It progressed to a literal mutilation of meaning and the grammatical structure through how you space words and letters on a page or overlay words to make them illegible. Her actions open up another kind of space of memory of how those who have been silenced and how they might be remembered or not. It's a really powerful gesture for me for how to write counter histories. It's not an easy process. I shared images of the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia at the end of my talk, precisely because working with the project’s historians to determine the historical record for enslaved community at the university meant going through the work ledgers and personal letters of slave owner professors. The first draft of those citations was a list of violent acts and erasures. I opened the file and quickly closed it after reading its contents. As designers and historians we recognized we had to rehumanize the enslaved, how do we make them into a community, how do we represent what we know and also what we don't know? How do we share with the public that the enslaved were workers, that they may have had pride in the bricks that molded or laid, and that they were members of families? They were sons and fathers, they were daughters and mothers. When you visit to the memorial, you will see 4000 “memory marks,” horizontal gashes in the granite that mark the violence of the erasure of their names from the historical record—forgetting as an act of racial subjection (Figure 3). I do believe there are ways of producing histories in these different registers. I agree completely with Swati about the small spaces and the small acts, and about finding what is in the margins of the archive.

Figure 3. Höweler + Yoon Architecture, detail of the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, Charlottesville, VA, completed 2020. Courtesy of Höweler + Yoon Architecture.

SC: It's about the materiality of the text. It's about the materiality of the wall. It's about changing. If you change the materiality, you change the power of it and its agency. How do you understand it, how do you interact with it? My point is that when you write political graffiti, you are changing the materiality of the wall, showing that it is actually amenable to reinscription. You’re refuting the given of the state. Just as in the examples Mabel shared, you’re refuting the authority of the archive and the documentation process. For architectural historians, we are concerned with materiality, but we often don't connect the materiality of the text with the materiality of the built environment. How do they belong, and don’t belong?

PC: I'm going to try to take us beyond words for one moment and address a question which came from Anne Marshall, “The primacy of the written word marginalizes people from oral cultures or those without the privilege of literacy. Could you comment on sources beyond the written word?”

SC: When I was working on Unlearning the City, I was struck by what barely literate people understand and read. One of the chauffeurs who would drive me around the city barely knew how to write. He could barely sign his name, but he could read every sign. He could react. There's a habit of understanding the world through images and sort of quasi-text. When we are literate, we don't have that perspective. We have a little of that when we're in a foreign location and we don't understand the language: when you we are desperately trying to understand what the heck is written on the signboards. We get a sense of that feeling. I think we underestimate people's capacity to understand the material world, even if they are illiterate. So no, you don't have to look at texts always. But we don't always look at texts. One of the great things about the materiality of the wall is, you know, there are all those images. And people understand, and see in amazing ways.

MW: I had a conversation in my seminar with the anthropologist David Scott, who has a really great essay, “That Event, This Memory: Notes on the Anthropology of the African Diasporas in the New World.” Scott challenges the reliance on narrative and discourse in anthropology, in particular, the way in which history enters into anthropological study for verification of what is true or untrue. He raises this in relationship to the retention of so-called Africanisms in New World Blacks in the works of Melville Herskovitz, Franz Boas, Sidney Mintz, and Richard Price, all of whom utilize the colonial archive for verification. For Scott, this reliance is profoundly problematic and instead, he suggests it's more useful to look at what he calls “tradition.” Even though that has a conservative overtone, he argues that tradition can be found within everyday practices, in the ways in which people relate to one another, in the kinds of quotidian practices that articulate their identities. A tradition can be contested, it can be lost, forgotten, and it can be passed on. But for him, tradition becomes a much more fertile ground for understanding certain resonances than the authentication of history in through the archival evidence.