What Pictures of People Reveal About Historical Streetscapes and Soundscapes

The street is a space defined not only by buildings but also by the sights, sounds, and smells generated by the activities it frames. To understand it, we must explore not just its physical form but its sensory landscape.

The engagement of the senses is most apparent in the transformation of retail trade. Perhaps more than any other factor, the street has been molded by buying and selling. One of the major changes in the street since the seventeenth century was the enclosure of shops, as barter and sale through the shop window was replaced with interior transactions (figure 1). The change in shop design was part of a broader migration of retail away from the street as a result of factors such as the regulation of traffic flow and sanitation as well as greater stratification and exclusivity in retailing. This is a history that begins with hawkers and open-air markets, continues through arcades and shopping malls, and perhaps may end with the complete disappearance of shops.

Figure 1. Jan and Caspar Luiken, The Brushmaker, 1694. New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

While attempting to reconstruct the transformation of European shopping streets between the Renaissance and the automobile age for my new book, The Streets of Europe, I stumbled across a rich trove of materials: the images known as “street cries,” produced in great numbers by graphic artists and commercial printers. From roots in the Middle Ages, the genre blossomed with the invention of printing and, remarkably, thrived for centuries. There are early printed examples from sixteenth-century France and Italy, after which they proliferated in seventeenth-century Paris and became common in cities across Europe by the eighteenth century.

Commercial printers churned out the work of engravers who often adapted their images from paintings, including some by such major artists as Annibale Carracci and François Boucher. The typical print was a broadsheet arrayed with rows and columns of individual portraits, one for each recognized street trade in a city. Each trade was represented by a single figure displaying the trade’s characteristic gender, costume, posture, and tools or merchandise: women or girls selling fruits, vegetables, and flowers (and also milk) while men or boys shined or repaired shoes, played barrel-organs, and hawked pots and pans (figure 2). Separate prints of single figures also became common. Increasingly, in later centuries, the trader appears in a streetscape or, less frequently, is shown interacting with customers. By the eighteenth century, some prints had become tableaus of urban life. By the early nineteenth, they evolved into urban genre scenes and acquired a hint of nostalgia. In the course of that century, the tradition went into decline, although the invention of photography and of picture postcards briefly gave it new life.

Figure 2. Street Cries. Printed by van der Haeghen, Ghent, c. 1860. Rijksmuseum/Wikimedia Commons.

These images recorded aural as well as visual memories, hence the name “street cries” or the “cries of Paris” (or London or Hamburg). In a world where sound recording was inconceivable, the pictures evoked the familiar cries of every trade. Each had its recognizable phrase, meter, and even melody. Typically the prints show the trader in the act of uttering his or her tune or phrase, and often the words are printed next to the portrait (figure 3). Some even included musical notation of the trade’s familiar tune, enabling purchasers to carry the music of the streets home to play in their salons.

Figure 3. Marcellus Laroon, “Buy my fat chickens,” c. 1700. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection/Wikimedia Commons.

The genre is familiar to art historians, but less so to urbanists, and it came as a revelation to me when I was casting about for scarce information on hawkers. It led me to think anew about the relationship between shopping and the city street. I also began to think more about sound. The aural identity of the street—its soundscape—is little known, largely because it is difficult to reconstruct. Fortunately, the prominence of hawkers’ cries is not only apparent in the tradition of prints. Renaissance composers such as Clément Janequin and Orlando Gibbons, and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century opera, adapted street cries. There is also a visual and verbal tradition of complaints about the noise made by street hawkers and entertainers. The most famous example, William Hogarth’s 1741 print “The Enraged Musician,” condenses many Londoners’ grievances into one crowded scene (figure 4).

Figure 4. William Hogarth, The Enraged Musician. Engraving, 1741. Library of Congress.

My training as a historian led me to seize upon these images first of all as readily available illustrations of the street trades I was writing about. But the work of scholars better trained in visual material reminded me that causality worked both ways: while the presence of the traders may have inspired artists to leave us these images, their proliferation shaped broader public memories of urban space. The fact that this genre of prints remained commercially viable for centuries not only tells us that hawkers long shaped the visual and aural space of the street, but also suggests that the hawkers were widely seen as the visual and aural icons of urban life in general, for all the particular differences between “the cries of Paris” and those of London or Rome or Vienna (or even New York). Prints of “street cries” were presumably purchased as souvenirs of a city.

Figure 5. Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, Part of East Side, Regent Street, 1828. Wikimedia Commons.

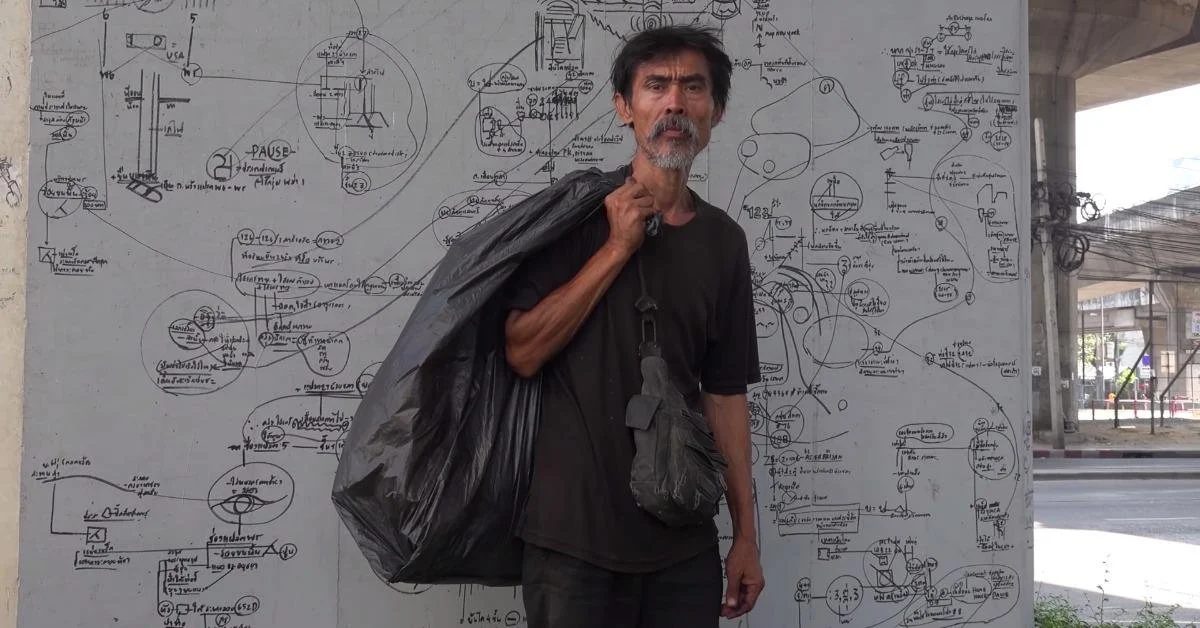

Throughout this era consumers had access both to street hawkers and to fixed shops. Gradually, the shops became more numerous and offered a wider variety of goods, leaving fewer opportunities for hawkers. Especially from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, enclosed shops with display windows replaced open-fronted stalls, marking a firmer separation between shopkeepers and hawkers (figure 5). This enclosure transformed the interaction between merchants and customers. Increasingly, it began not with cries and gestures but with window displays or with the silent cacophony of printed verbiage on signs and walls (and eventually phones) (figure 6).

Figure 6. John Orlando Parry, A London Street Scene, 1835. Wikimedia Commons.

Although we lack direct evidence of the sounds of the historical city street, these images reveal a lost world in which communication was aural more than visual, before cries were silenced by glass display windows and a proliferation of signs and advertisements. Most remaining hawkers were eventually chased away, ignored, or drowned out by the growing mechanical din that has become our urban soundscape.